As demand for recovery houses rises, Bucks lawmaker seeking Pa. certification

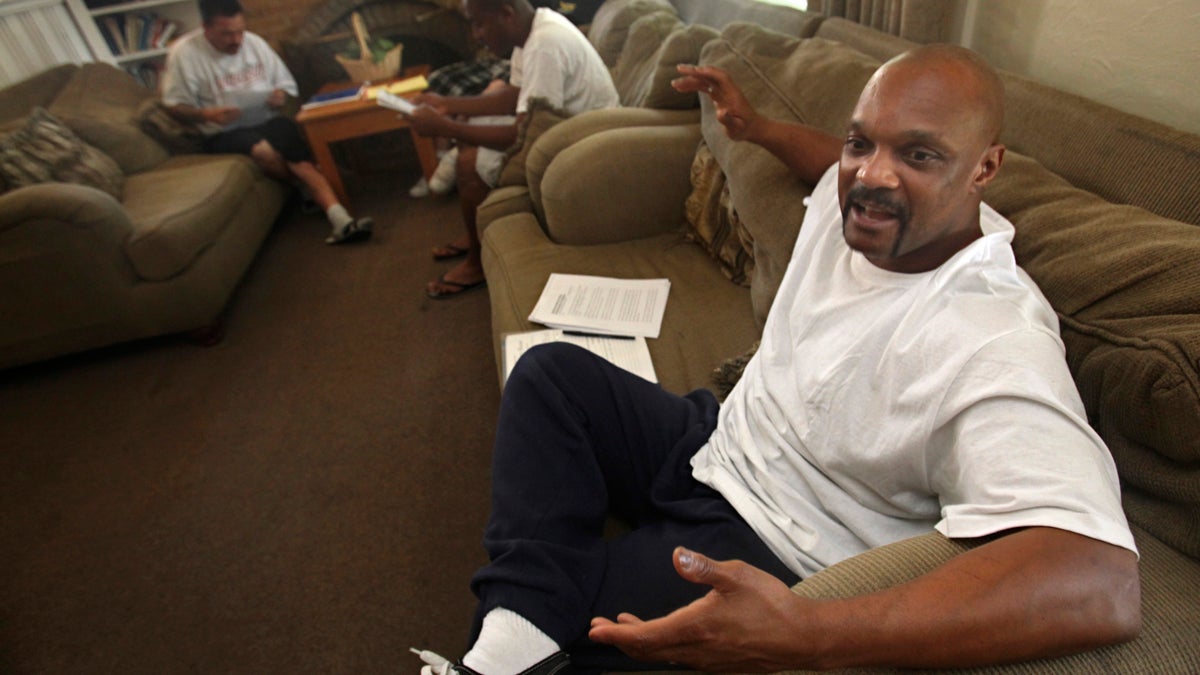

Christopher Williams, right, joins in during a discussion group for drug abusers at the Sacramento Recovery House in Sacramento, California. A Pennsylvania legislator has introduced a measure calling for state certification of such facilities. (AP file photo)

Recovery homes are not new, but their increasing numbers in some parts of the Delaware Valley are, according to a state legislator from Lower Bucks County.

“When I left [Bristol Township] Council in 2010, there were maybe 25-30,” said Pennsylvania Rep. Tina Davis, D-Bucks. “Now there are at least 90,” in that municipality alone, she estimated.

Davis this month introduced a bill to have the state certify and regulation of recovery homes, sometimes called sober living homes. The measure calls for creating a board to administer a certification for recovery houses. And, in order to be certified, the houses and their management would have to pass background checks and enforce the sobriety of residents, among other rules.

Opioid addiction is on the rise around the country. In its wake, recovery houses have boomed in some parts of the Delaware Valley.

Officially, a recovery home is “a supportive environment where residents in recovery live together as a community,” said Jason Snyder, communications director for the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs.

The department regulates treatment centers but not the recovery houses, said Snyder, because the housing operators don’t provide a service.

Even though they don’t offer counseling or administer medication the way a treatment center does, sober and safe housing can be a factor in maintaining sobriety.

“Lack of a stable, alcohol- and drug-free living environment can be a serious obstacle to sustained abstinence,” according to research from the National Institutes of Health.

Officials in Levittown, Bristol Township, Bristol Borough, Falls Township and Middletown Township in Bucks County have held discussions about zoning for an evident — or anticipated — spike in recovery houses. Only a handful of states, such as Massachusetts and Ohio, certify the sober living homes.

In 2014, Pennsylvania’s Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs helped start a task force intended to produce recommendations for certifying recovery houses, with the understanding that while most places operate safely, “others are less scrupulous, potentially exploiting people who left treatment but need a place to live,” said Snyder. He said he wasn’t sure when the task force, established by a bill from state Rep. Frank Farry, would share its recommendations.

Davis said she couldn’t wait any longer to put a plan to certify the houses into the world.

“What bothers me is, we just did a barber’s licensing bill,” said Davis. “I’m not putting down barbers, but this is so important. No one wants to look at this?”

The future of the bill, at least in the short term, is not bright. New programs are hard to plan or pay for in Pennsylvania, now eight months into a state budget impasse, said Davis. She expects the bill to be heard by the Pennsylvania House of Representative’s Human Services Committee in March or April.

While the bill makes its way through legislative channels, inspection and the certification continues ad hoc, run by local certification organizations.

Seizing an opportunity, mental health expert Fred Way created the Pennsylvania Association of Recovery Residences, which evaluates and certifies recovery houses. The vetting process runs the gamut from inspecting the houses for basics such as running hot and cold water to interviewing operators about their qualifications, according to Way.

So far, 61 recovery houses in Pennsylvania are PARR certified, he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.