‘Tree huggers’ of Arden battle to cut down Delmarva Power’s plan to replace electric towers in their village

The project aims to improve reliability in storms for 13,000 customers. Opponents want it rerouted amid environmental, health concerns.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Standing at the base of a soaring electric transmission tower between her neighbors’ homes, Lisa Wilson Riblett bemoans the fate of a 30-foot swath of existing plant life and property.

The retired educator fears clear-cutting and the disruption of lead-contaminated soil if Delmarva Power moves ahead with plans to replace several of the giant steel structures that cut through Ardentown in northern Delaware.

“Look, you have this person’s backyard, you have their fence, you have all their trees, you have the foundation for the brick patio,’’ she said. “They’re talking about ripping all the way through here and leveling everything all the way down. It’s disrespectful to the environment, disrespectful to the residents.”

She pivots and gazes the other way along the snow-covered stretch of ground, where another tower looms above the landscape.

“There’s magnificent native holly trees and native arborvitae trees,’’ she said. “And just think of that 30-foot swath, completely mowed down.”

What Wilson Riblett is so distressed about is “The Silverside to Naamans Reliability Project,’’ a 4.5-mile system upgrade that Delaware’s leading electricity supplier has been planning for years.

The work entails replacing existing transmission towers that were built a century ago on the company’s existing right-of-way through what was then farmland. The goal is to improve reliability for more than 13,000 customers while reducing the frequency and duration of outages, according to Delmarva’s fact sheet for the project.

The utility plans to use galvanized steel towers, capable of withstanding hurricane force winds, and to use a design that reduces risk to birds, the fact sheet says.

While Delmarva has pledged to work with residents and property owners to “minimize potential impacts,’’ Wilson Riblett said it has barely amounted to lip service and has elevated — not alleviated — concerns in Ardentown and Ardencroft, two of the three tiny municipalities in the wooded enclave known as The Ardens that would be affected.

Seven towers that traverse about a half-mile of mostly hilly terrain cut through the two towns. The village’s third incorporated municipality, Arden, is west of the transmission route and won’t be impacted.

The towers do appear out of place in Arden, an artsy enclave near Delaware’s northern tip that was founded in 1900 as a community of summer cottages. The village was designed with several large “greens” — undevelopable open spaces — between the homes.

To live in The Ardens, which is surrounded by and infused with mature woodlands, where hedges border most properties, and no sidewalks or streetlights are found, is to be immersed in what the town calls its “forest ecosystem.”

Not surprisingly, many of the 400 residents, as Wilson Riblett points out, are “tree huggers’’ like herself.

“Our forests and greens are incredibly important to us. And we work really hard to get rid of invasive [species] and to plant native trees,’’ she said. “And hearing that they were going to level to the ground was just totally unacceptable.”

Delmarva’s ‘dismissiveness and deception’

Since becoming aware of Delmarva’s plans last year, Arden’s leaders have taken these actions:

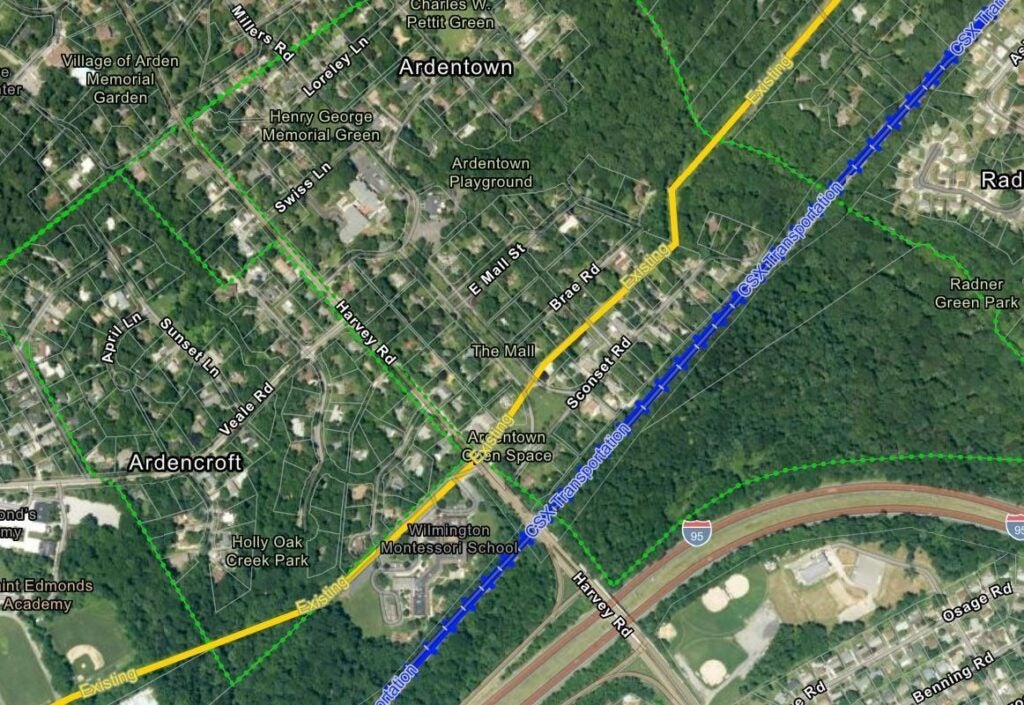

- Urged Delmarva to re-route the project about a quarter-mile to the east, where the CSX railroad tracks lie. Delmarva already has some towers near CSX tracks that are south of the disputed project.

- Conducted soil studies that found high lead levels from old paint once used to coat the structures. They alerted the state Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Resources, which is now monitoring Delmarva’s lead remediation plan.

- Passed an ordinance in Ardencroft that bans new transmission lines and towers, and charges an unspecified annual impact fee for the existing transmission infrastructure, billable every June. Ardentown is likely to pass a similar law, Wilson Riblett said.

The village also has created a website to detail their concerns and proposals.

Wilson Riblett, who heads an Ardentown subcommittee focused on the project, and Ben Gruswitz, an urban planner who is Ardencroft village assembly chair — effectively its mayor — say Delmarva has basically blown off their pleas and requests.

In November, for example, Gruswitz asked Delmarva in writing to conduct a feasibility study for other transmission routes, such as along the railroad tracks.

“This realignment offers numerous benefits, including reduced health and environmental risks, alleviated housing impacts, and improved efficiency by continuing the consolidation of transportation and utility infrastructure along the [rail] corridor and away from schools and communities,’’ Gruswitz wrote.

“By moving the lines away from residential and forested areas, we can greatly reduce environmental and health risks while preserving the character of our communities and natural habitats.”

State Rep. Larry Lambert, who represents Arden, followed up with a separate request to Delmarva for such a study. Lambert’s letter noted that the lead levels exceeded state and federal safety limits, including “one as high as 11.5 times the standard for residential areas.”

Contaminated soil like the patches found in Ardenton and Ardencroft should not be used for vegetable gardening and children should not play in it, according to the University of Delaware’s Soil Testing Laboratory.

Lead exposure can lead to developmental delays in infants and children, and to heart problems and other ailments in adults, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

While Delmarva is removing the lead-laden soil beneath the towers, the utility is otherwise staying the course.

Phillip J. Vavala, the company’s regional president, responded to Gruswitz with a letter that repeated many of the fact sheet talking points. Vavala also wrote that while rerouting the lines might seem like a “quick fix,” especially moving them to the railroad tracks, “our engineering teams determined during the planning phase of this project that alternative routes were not viable or feasible due to congestion in the region.”

Gruswitz’s rebuttal to Vavala, which he copied to then-Gov. John Carney, Delaware’s congressional delegation and local elected officials, didn’t sugarcoat his displeasure.

He wrote that Vavala’s response “leaves several critical concerns unaddressed and falls short of the transparency and diligence that we, as an impacted community, require and deserve.”

Asserting that Arden deserved “substantiation” from Delmarva of its claims that alternate routes had been thoroughly considered, Gruswitz wrote that “without clear evidence — such as route analysis studies, maps, or other supporting documentation — we are left with only your assurances, which are insufficient given the context.”

“Delmarva’s history of evasiveness, dismissiveness, and deception has forfeited the trust necessary to simply take your word on this.”

Delmarva: Moving towers would cost millions

Vavala did not respond to requests from WHYY News for an interview about the project and the concerns from Arden’s leaders.

Instead, utility spokesman Francis Tedesco agreed to speak with WHYY News and scheduled time for the interview. But Delmarva abruptly canceled the interview and Tedesco sent a written statement that reiterated many of the fact sheet points and said the utility was studying the new transmission line ban and the impact fee ordinances.

“We conducted a review of potential route options and identified these upgrades as the least impactful option to modernize the local energy grid, improve reliability and meet the future energy needs of our customers,” Tedesco wrote.

“Alternative routes would result in millions of dollars in additional costs to our customers, an increase in transmission poles required and were not feasible in certain locations due to existing needed infrastructure.”

Tedesco said company tests “confirmed the presence of lead on 17 of the tower structures planned for removal and in the nearby soil,” including 10 located elsewhere on the 4.5-mile replacement route. Those results were shared with state environmental officials and Delmarva enrolled in the state’s “Voluntary Cleanup Program,’’ he wrote.

“We anticipate completing the cleanup prior to the start of construction for the transmission line upgrade,’’ which he said would begin in spring 2026.

Tedesco also noted that every four years Delmarva cuts back trees along the route that surpass 60 feet in height, Tedesco said the project will also require some “vegetation and tree trimming” as well.

“We are committed to maintaining the health of our environment by conserving, protecting and enhancing our natural resources,” he said.

Arden fears ‘continued impacts for the next century’

Gruswitz said Arden is now studying how to best stop Delmarva’s plan to plow ahead, but noted that the little towns have small budgets — Ardencroft’s budget is about $50,000 a year — and stopped short of saying they would pursue legal action.

Delmarva, by contrast, is part of Exelon Corp., a Fortune 500 conglomerate that had $21.7 billion in revenue and $2.3 billion in net income in 2023.

“If entities work together in good faith, they are transparent with each other and seek to gain trust,’’ Gruswitz said. “In all my interactions with Delmarva, they seek some sort of shortcut to the trust part with even attempting to gain it.”

“Delmarva’s plan to plow ahead ensures continued impacts for the next century,” he said. “Delmarva needs to share what options they explored and what their criteria for impacts is.”

Gruswitz also questioned how Delmarva calculated the additional costs to power customers from using a different route that didn’t cut through the residential area.

“They can’t make unqualified ‘millions of dollars’ for customers a boogie man to shoo people away with no transparency … And you can’t say you’re ‘working with community groups’ if you ignore their concerns,” Gruswitz said.

The bottom line, Wilson Riblett said, is that Arden should not suffer from Delmarva’s project.

“When you’re a small village with only a couple dozen people that are affected and up against Delmarva, who’s a huge conglomerate, they politely blow you off,’’ she said.

“They have a sea of lawyers and a sea of people and we’re just small town folk trying to protect our woods and our people and our health.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.