Figuring out how to make Philly work better

July 21

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

Local and national experts in sustainable and regional planning will gather at The University of Pennsylvania this week to ponder the idea of transforming the Philadelphia region into a more vibrant, eco-friendly and globally competitive place.

In a nutshell: Attendees will closely examine the current conditions, assets and liabilities of the region and city. Then, they will attempt to determine how a limited amount of resources could best be invested in order to make the biggest possible improvements.

Key concepts include planning future job and residential growth along transit lines and in centralized locations – both in the city and the region – and the better use of the current infrastructure, including buildings and groups of buildings that may now be abandoned or under-utilized.

“I think we can change the future of Philadelphia – protect the legacy, but move forward to dramatically increase the competitive advantage of the city,” said Penn School of Design Dean, Marilyn Jordan Taylor, the driving force behind the three-day roundtable which began Monday night. She hopes that at least some of the ideas generated will one day become real life components of a region with plenty of good-paying jobs, highly desirable neighborhoods, and mass transit to take residents to and fro.

Taylor cares about this region’s distant future and appreciated a recent exercise in which top city planning officials joined Penn professors and students in an intense studio course that looked at what Philadelphia might resemble in 2040. But it’s what happens in the near term – how the region uses the economic slowdown for planning, how much economic stimulus money it can attract, and how it invests those limited dollars – that will strongly influence the middle of this century and beyond, she said.

“I am really interested in what happens over the next five years – in what can happen over the next five years – and how particularly in this economy, in this presidency, public money can be invested in a framework that makes those kinds of longer term visions somewhere between more likely and inevitable,” Taylor said in a recent interview at her office.

Three days of crunching ideas

The Penn School of Design, PennPraxis, The Penn Institute of Urban Research and the City Planning Commission have worked together to design the upcoming session. The William Penn Foundation is picking up the tab.

The charette itself is invite-only, but a public lecture on the same topics will take place the evening of the last day, from 5 to 8 p.m. on July 29 at the Academy of Natural Sciences. The ideas generated during the three days of work will be compiled into a report that will be presented to the city and the public sometime this fall. The goal is that the report will be “used in a way that advances the city and region on a national level,” said PennPraxis Executive Director Harris Steinberg. He’s not just talking about planning. The report could be shown around Washington, D.C. to demonstrate to the people doling out the federal dollars that the money would be well spent here, Steinberg said.

Taylor sees the charette as an example of how a city can use partnerships with its universities and foundations to get things done in times of tight budgets, and she thinks this workshop and partnership could be duplicated in other places.

Participants at the invite-only session include Alex Krieger, Founding Principal, Chan Krieger Sieniewicz, and Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Design, and Trent Lethco, a transit-oriented development expert who is a senior planner with ARUP Inc’s New York City office.

Members of the Obama administration who can discuss the President’s urban initiatives and provide a broad-scale view of the current economy are expected to attend. So are environmental and housing advocates, a host of planners, architects and economists, representatives from transit authorities and universities around the region and officials who represent towns and cities in this part of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware.

Participants will look at how to improve the region as a whole, Taylor said. But the key to any prosperous region is a healthy urban core, so they will spend time looking closely at Philadelphia, especially at the Naval Square area near the Penn Campus as well as the port and the airport.

The decision to drill down at these locations was made in conjunction with City Planning Director Alan Greenberger and the former mayor for economic development, Andy Altman, who is now designing London’s Olympic village. The plan is “to create some large-scale, urban design ideas” that City Planning can use, Taylor said. “We’re going to look at what kind of development could occur there to the city’s advantage. And how it links to regional rail and commuter rail.”

The Marshall Labs/Naval Square parcels are underutilized, but could be more fully developed “as a way of expanding clean industry, the health center industry and research that can complement the more academic and more service sector jobs that are in Center City and slightly to the North,” she said.

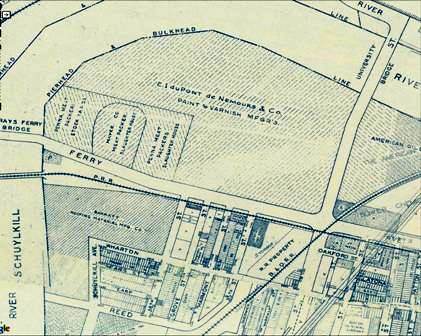

1962 land use map

Present aerial view

The work related to the port and airport will focus largely on transportation. “All great cities that have a competitive place in this global climate have ports and airports that reduce the time in travel for people and goods,” Taylor said.

The Philadelphia region needs to be careful not to set up the wrong chain of events, Taylor said. She used a nationwide example to show how good intentions can have bad results: The 1950s era investment in public highways.

It seemed like a really good idea at the time, she said. People and goods could move more quickly and easily around the country – and if the Cold War ever got hot, tanks, supplies and troops could also be positioned efficiently.

“Something that seems like a public good draws a huge amount of money, and has enormous, unintended consequences,” she said. “It’s clear that the investment in what became the interstate highway system not only supported suburbs and sprawl, but also made it much easier for the Northeast and the Upper Midwest to lose transportation to the newly accessible, more temperate and in fact even hot areas of the South and the Southwest.”

In other words, Taylor said, “When we make public investments in physical infrastructure, there’s an implicit land use policy.”

And there’s definitely some serious sprawl here, Taylor said.

Where the people and jobs are

A group of eight 2009 Penn graduates, most of whom participated in the Philadelphia 2040 studio, jumped at the opportunity to participate in the charette because they believed the event is emblematic of the level of thinking that needs to be encouraged about planning and development issues in Philadelphia.

They call themselves The Planning Collective. At the request of John Landis, Penn Crossways Professor of City and Regional Planning, the group set out to create a visual representation of where people in this region live and work that information will be used during the charette. What they found is that people live and work everywhere here. “By and large, compared to some other places, the jobs and the people are kind of scattered. Even jobs are sprawling here,” Taylor said.

The regional transportation system was designed at a time when the most jobs were in the city. Even as people moved into the suburbs, many commuted in to the core urban areas. Many still do, but the concentration of jobs and homes has become much more diluted. Lots of people live in one suburb and commute to work in another suburb, for example. In that scenario, there may not be an easy commute via public transportation.

What this means, Taylor said, is that if the region’s goals include less dependence on cars and fossil fuels and in improving air quality and preserving green space, we need to “find points of concentration” for jobs and residences.

That doesn’t mean everyone must live and work in Philadelphia, she said. It means directing future growth to targeted areas that are already served by public transportation – or could be with little investment. “There could be more rides from Center City to employment across the region,” she said.

Even though this region has a growing sprawl problem, it does have existing centers of concentrated development in its urban roots, many of which were first developed in the days when people walked to work. Some of these older places are now underutilized, or even abandoned.

Not for too much longer, Taylor predicts. Not with the shrinking supply of resources. “We’ve got to do a lot more with less,” she said. “We’ll be looking more at retrofit and reuse. Where we have already disturbed, where we already have services, where we already have or can easily gain access to transit, those places I believe will become increasingly privileged in the investments that we make.”

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.