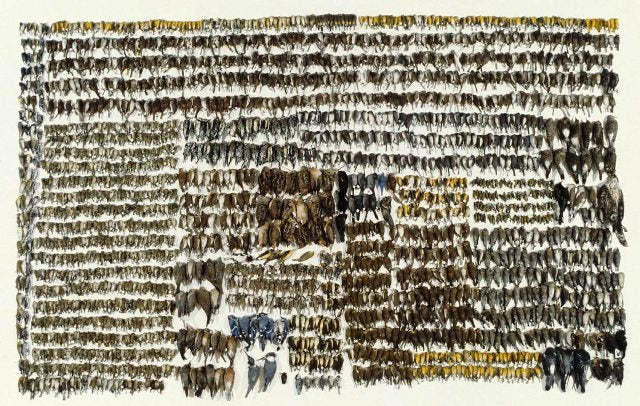

Birds, lights, glass = fatal mix

Photo: Toronto casualties

Mar. 5

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

Hours before the sun arrived in Center City, Valerie Peckham was searching for birds. But this was not typical bird watching.

During that outing last fall, the Philadelphia Zoo’s conservation program coordinator mostly kept her eyes focused on the ground. The birds she was looking for would be dead – killed when they flew into windows they could not see.

Peckham was tallying bodies with Nate Rice, the ornithology collection manager at the Academy of Natural Science, Keith Russell, Pennsylvania Audubon‘s outreach coordinator and a small group of volunteers. They hope the information gathered will help convince Philadelphia to join Chicago, Toronto, New York and other North American cities that have programs designed to protect birds from fatal window collisions.

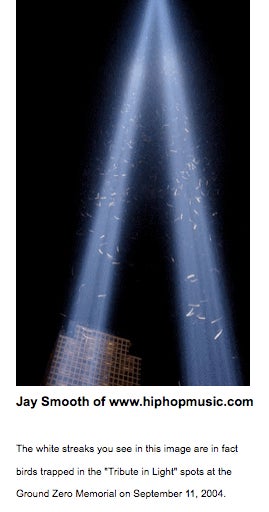

Put simply, the problem occurs because birds, which migrate in the dark and use the stars to navigate, become confused by the bright lights of city buildings.

“Once birds enter a beam of intense light, they swirl around in a confused manner and become exhausted. This is where the tragedies are occurring,” said Daniel Klem Jr., a professor of ornithology and conservation biology at Muhlenberg University in Allentown. He has studied the problem for more than 35 years.

Sometimes the birds fly into the lit buildings, sometimes they fly into each other. But most deaths occur later, when birds attracted by the light fly into a pane of glass while searching for food, water or shelter. Whether the glass is reflective or clear, the birds just do not see it, Klem said. They fly into clear lobby glass while trying to get to trees or fountains inside, he said. Or they think they are about to land in the next tree, but the tree turns out to be just a reflection.

“There are estimates that up to a billion birds die this way every year” nation-wide, said Russell, who received a grant from Toyota to help pay for the Philadelphia monitoring project. “This might be one of the biggest causes of bird decline right now, next to habitat loss.”

An earlier attempt to get those who own and manage Philadelphia buildings interested in a prevention program fizzled, but the director of their membership organization said he would be willing to talk again if the advocates can show there’s a problem here.

The spring migration, which begins this month and ends in early June, is smaller than the fall migration, which includes the young birds born that year. It is estimated that 5 billion individual birds of about 200 species fly from North America to South and Central America each fall. About half that many survive and return north to their breeding grounds in spring.

Soon, the same group of volunteers will be back at their undisclosed Center City location, again counting the birds that don’t make it.

Last fall, the advocates counted birds on 35 mornings, with seven people covering a 2.5-block square area. They found 62 dead birds, and 11 injured ones. “We know that there were many more,” Russell said. Some birds fall onto ledges where people can’t reach them, he said, and others are eaten by predators, smashed by cars, or swept up by people. “I suspect the numbers are closer to 100 per month,” within the 2.5- block area, he said. Extrapolate that over the entire city, Russell said, and it’s a big problem.

Rice said the birds found were mostly songbirds, plus a few woodpeckers. But woodcocks and rarer warblers, including the Magnolia, Canada, Chestnut Sided and Blakpoll have also been discovered.

He does not think Philadelphia’s problem is as severe as Toronto’s and Chicago’s, where thousands of birds used to be found dead in a single day.

Peckham said she’s sure the problem is different – Chicago is on a lake, for example. But she is not ready to say it isn’t as severe. She notes that three migratory flyways merge near Philadelphia.

“The streets aren’t littered with dead birds,” Peckham said. “But it’s a compounding problem when you factor in how many buildings there are in the city, and how long the migrations last.”

To remedy the bird-window collision problem, the experts say, buildings must be made less attractive to birds, and windows must be made more visible.

During migration seasons in Chicago, Toronto and New York, program participants switch off as many lights as possible – especially those on or near the tops of buildings. Just this step alone prevents many bird deaths and injuries, said staffers from Chicago and Toronto.

Building owners and managers are also encouraged to pull curtains or blinds where lights can’t be turned off, move plants or fountains that birds can see through windows, and add commercially available film that makes windows visible to birds. Those building new structures or additions are encouraged to use bird-friendly design, which includes using special glass that birds can see, careful placement of plants and water features, and other elements.

Volunteer monitors track dead birds and rescue injured ones – just as Russell, Rice and Peckham are doing here. They also work with program participants to help them find the places on their properties where the most birds are dying, figure out why, and come up with a solution. Chicago Bird Collision Monitors handles this in their city. Toronto has FLAP, which stands for Fatal Light Awareness Program.

Watch CBCM video

So far, participation has been voluntary in the cities with programs. But starting this fall, Toronto will require all new buildings to be designed with bird safety in mind.

Chicago has had a program since the late 1990s, said Annette Prince, Bird Collision Monitors director. Comprehensive tallies didn’t start until the organization attracted more volunteer monitors in about 2003, she said. By that time, nearly every large Chicago building was part of the program, at least following the minimum requirements that all lake front buildings and any building more than 40 stories turn off display lighting and lights on antennas, clock faces and corporate logos during peak migration flight times.

Prince wishes more building managers would go further, but just turning off the display lighting has had a big impact. “We no longer find 100 birds at a single building, although we can find several hundred (across the city) in one morning,” she said.

The Philadelphia advocates say any steps a building takes to lessen the problem would be a help, so participation here need not be all or nothing.

If employees are working at night, Rice said, they could turn off overhead lights and use downward-facing task lighting, or turn off the lights when they leave a particular floor.

The attraction and confusion of city lights is most problematic during cloudy nights, Klem said. “If it’s a clear night, they will pass over no matter how bright the lights are, and go on their merry way,” he said. So Rice imagines some sort of lights-out alert system that would allow participants to know the most critical nights.

Rice, Russell and Peckham can’t yet tell how many birds die in Philadelphia due to window collisions. Peckham hopes the group will be able to take at least some preliminary numbers and suggestions to the City and the Philadelphia Building Owners and Managers Association this summer. She also hopes that those in charge of some buildings will volunteer to become part of a pilot program for the fall migration.

Russell said that in addition to knowing more about the problem, he’d also like to be able to have solid examples of steps that have worked at Philadelphia test sites before approaching the city about taking a program city-wide.

Philadelphia Building Owners and Managers Chairman Richard McClure said he spoke to some of the bird advocates – and then to his members – in 2006.

“The last time we put this concept out to our members, the feedback wasn’t supportive,” he said. The owners and managers of BOMA operate each of their buildings under a unique set of circumstances – sometimes including legal obligations making it impossible for them to turn out the lights, he said. “Their lease obligations may state the crown on the building needs to be illuminated, or may include tenants’ rights to signs on the roof, and illumination for those signs,” McClure said.

McClure said his membership has not noticed a lot of dead birds, but he asked the advocates for evidence in 2006, and if they bring some to him, he’ll look at it. “If there’s an issue out there, we’d like to know about it,” he said.

McClure noted that back in 2006, Philadelphia had just lit up City Hall, and asked that nearby buildings shine lights on the building.

But now, some buildings are turning out lights at night – to save resources and money, he said. That might help some birds, too, McClure said.

Toronto body count

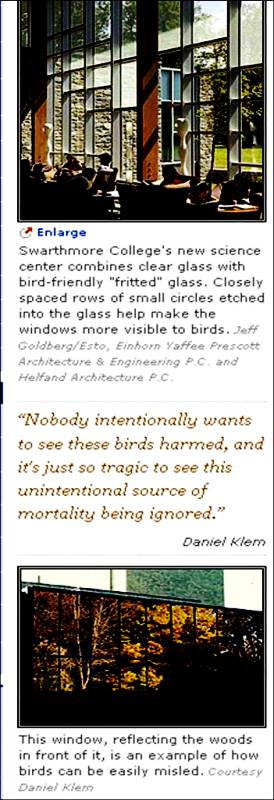

There is already interest in preventing bird-window collisions on two local college campuses: Temple University has signed on to be a second bird fatality tracking site for the spring migration, with student volunteers trained by the advocates to do the counting. Swarthmore College has been at it since 2006, when faculty and staff there worked with Klem to design a bird-safe science building.

Temple got involved after a faculty member noticed dead birds on campus, said Sandy McDade, the college’s director of sustainability. The faculty member spoke to President Ann Weaver Hart – an Audubon member – and Hart spoke to McDade.

“We are sensitive to the fact that we are a large urban environment, and not the greatest environment for wildlife,” said McDade, a self-proclaimed bird watcher. McDade hopes through its participation, the University will learn how big the problem is and what can be done to lessen it.

“This will help us as we build, and do renovations in the future,” she said. When it comes to existing buildings, “ultimately, things always come down to money,” she said. “To, say, replace all the windows, it’s not gonna happen.” But if there’s anything that can be done for little or no money – turning out lights, moving plants and the like – Temple will do it. “I’ve looked at Chicago’s Lights Out program, and it’s really fabulous,” McDade said.

Like some of the buildings in Philadelphia’s BOMA, Temple is already telling people to turn out lights at night to save energy, McDade said.

Swarthmore’s interest also started with a faculty member, ornithology professor Timothy Williams, who is now retired.

The university was beginning work on a new science center that opened in 2004, said associate engineering professor Carr Everbach, who was chairman of the Green Team, which was tasked with making the building as environmentally friendly as possible. Williams had heard Klem speak about bird/window incidents, and suggested that the Green Team bring Klem to campus to talk about solutions.

Swarthmore was already familiar with the problem. “There are 350 acres of old growth forest surrounding our buildings that is ideal bird habitat,” Everbach said. “We had problems for decades with birds flying into our buildings.”

One building, which has a garden, was especially problematic, Everbach said. “One year, we had something like a dozen hummingbirds, and one by one, they were found dead by the glass.”

The science center that the Green Team was working on had been designed with a large glass atrium, through which birds on one side could see the forest on the other.

This photo is taken through the fritted glass

To make the glass visible to birds, the committee decided to make use of something that had been around for awhile for artistic and energy conservation purposes: Fritted glass, which is glass with frosted patterns on it.

The trick was to find a pattern that would be seen by birds without being too much of an annoyance to people. Samples of several designs were displayed, and the sentiments of students, faculty and staff were collected. The same patterns were sent to Klem, who tested them to see if they would, in fact, dissuade birds.

Swarthmore spent about $24,000 extra to purchase fritted glass for enough windows so that there was no point at which a bird could see the whole way through the atrium.

People looking out these windows can see that they are different – they are covered with small, frosted dots. But anyone looking out can see a classmate or the trees quite well. The dots become blurry in an effect similar to looking through a chain-link fence. “It’s not invisible, but it’s tolerable,” Everbach said.

The university tracks bird strikes with sensors mounted to the glass, and since the building opened, there have only been four counted. “We got four strikes a week on other buildings on campus, and this (glass) curtain wall is huge, and situated in such a way that is very potentially bad for birds,” he said.

The glass, which saves on cooling costs by reflecting the summer sun off the building, is expected to have paid for itself sometime this year, Everbach said.

Gray Catbird / Dumetella carolinensis Order PASSERIFORMES – Family MIMIDAE

Rufus-sided Towhee / Pipilo erythrophthalmus Order PASSERIFORMES – Family EMBERIZIDAE

Common Yellowthroat / Geothlypis trichas Order PASSERIFORMES – Family PARULIDAE

Ever since the science building went up, students have been conducting experiments to search for an inexpensive, after-market way to make glass visible. One system involves putting epoxy dots on the windows with a gizmo that is like a motorized paint roller. “We found that it was effective in reducing the number of hits on the building that killed all of our humming birds,” Everbach said.

The bird-friendliness of the science building earned it innovation credits that helped it earn Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Certification.

The Philadelphia advocates hope that the tie-in with LEED and the potential energy savings of both fritted glass and simply turning off the lights will help convince builders, building managers and the city to at least encourage bird-friendly practices and design.

Next month, the volunteers from The Academy of Natural Sciences, The Zoo, Audubon Pennsylvania and this time, Temple, will again be counting dead birds.

The monitoring is bittersweet, Peckham said. She knows every bird found adds to the hard data that could lead to a Lights Out program in Philadelphia. But the work is also very sad, she said.

Peckham remembers one day last fall, when she heard a soft thud above her. She looked up and watched as a small mass of feathers and wings fell to the ground near her feet.

“It was a warbler,” she said. A yellow one. “It was like picking up a sleeping animal.” Peckham hoped it was just stunned, but after 15 minutes, she knew the bird was part of the tally.

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

ON THE WEB

Link to further information on bird fatalities

Pennsylvania spring migration chart

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.