1.5 million Pennsylvanians live close to large amounts of hazardous ammonia

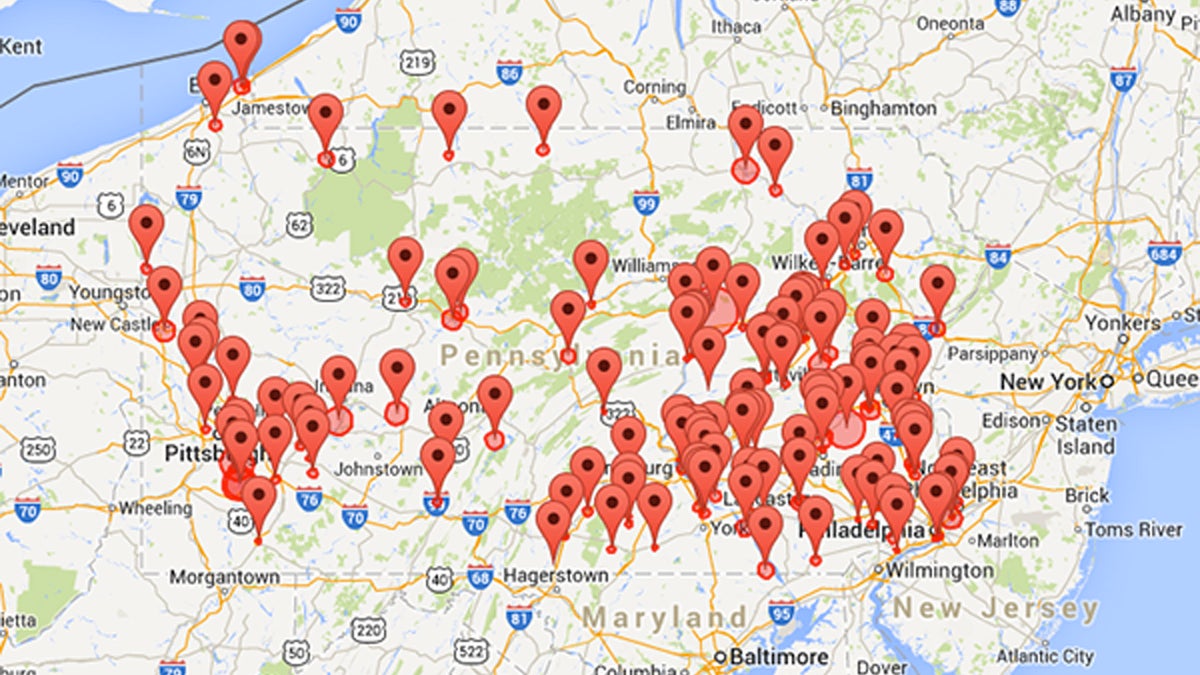

(Map by Alexandra Kanik/PublicSource)

Ammonia is the most widely used dangerous chemical in Pennsylvania. One in every eight Pennsylvanians — 1.5 million people — lives close enough to facilities that store large amounts of ammonia to be at risk in a catastrophic chemical accident.

Ammonia, a toxic gas the Environmental Protection Agency classifies as extremely hazardous, is the most widely used dangerous chemical in Pennsylvania.

One in every eight Pennsylvanians — 1.5 million people — lives close enough to facilities that store large amounts of ammonia to be at risk in a catastrophic chemical accident, according to a PublicSource analysis of federal records.

These records show what could happen in a worst-case scenario, where a large amount of hazardous chemical quickly leaks.

That 1.5 million includes only residents. It does not count children at schools, shoppers, people in office buildings, churches, hospitals and prisons. Nor does it include the 38,000 workers at the plants that use the ammonia.

The 122 Pennsylvania facilities that store at least five tons of ammonia at any one time include a list of companies with household names: US Steel, Giant Eagle, Wal-Mart, Sysco, Tyson Foods, The Hershey Co. and Yuengling Brewery.

“Having this information can only protect the public,” said Sofia Plagakis, a policy analyst with the Right-to-Know Network, a Washington research organization that advocates for better health and safety standards. “The public has a right to know if they are living near a high-risk facility in order to protect themselves, their families and communities.”

The RTK Network database shows that the 122 Pennsylvania companies are spread throughout 43 counties that must file risk-management plans because they use large amounts of pure ammonia.

One purpose of the risk plans is to help the public understand the dangers of hazardous chemicals and to see that the company has a plan in case of an accident. But, under EPA rules, one part of those plans, the worst-case scenarios, can be viewed only in government offices and an individual can examine no more than 10 reports a month.

At that rate, it would take one person more than a year to find out which Pennsylvania facilities handle large amounts of ammonia and how many people could be affected by an accident.

So, the PublicSource staff and six Point Park University journalism students examined all worst-case scenarios for ammonia in one day.

Now, for the first time, all Pennsylvanians can see how close they live to dangerous ammonia stockpiles. Summaries of the companies’ risk-management plans can be viewed on the Internet.

Burning, blindness

Most people know ammonia by its smell, or the odor of the much-diluted household-cleaning product.

Food-and-beverage makers use the pure form, known as anhydrous ammonia, to refrigerate their products; manufacturers to produce plastics, cleaners and explosives; farmers to fertilize crops, illicit drug-makers to make methamphetamine.

If it leaks, it vaporizes and binds to moisture in the human body. Small amounts irritate the eyes, nose, mouth and throat. More can burn the skin and respiratory passages or cause blindness. A large hit suffocates the person.

From 1996 to 2011, there were more than 900 ammonia accidents that killed 19 people and injured more than 1,600 in the nation, according to the RTK Network.

“It’s always a dangerous chemical,” said Randall W.A. Davidson, a risk-management expert in Littleton, Colo., who has inspected ammonia facilities. Accidents happen because companies neglect preventative maintenance or use untrained people, he said. “Because of that they have fires and fatalities.”

During the same time period, Pennsylvania had 18 ammonia accidents. No one was killed, but 27 people were injured.

An ammonia leak from just one facility, The Hershey Creamery Co., could harm at least 58,000 people in a major accident. Even lawmakers at the state capitol, less than a mile from the Harrisburg ice-cream maker, are sitting ducks.

In 2002, the Creamery hired a consultant to inspect the ammonia systems at its main factory in Harrisburg and a warehouse seven miles away in Middletown, where they use the chemical to refrigerate ice cream, according to federal court records. (This company is unrelated to The Hershey Co., which is the candy-maker.)

He proposed 46 safety measures but his recommendations were “essentially unimplemented,” he later reported. In 2004 Hershey certified to the EPA that it had risk-management plans at both plants, even though there were no formal inspections, no testing, no preventative-maintenance program and no evacuation plans for workers, the records said.

The company has a history of regulatory violations and paid a $100,000 fine to the Occupational Health and Safety Administration in 2004.

In 2008, the Department of Justice charged the Creamery with violating the Clean Air Act from 2004 to 2007. It was the first criminal prosecution in the nation for failure to develop and implement a risk-management program. The Creamery pleaded guilty and paid a $100,000 fine.

The company passed an EPA inspection in 2007.

Walter Holder, a vice president identified in EPA records as the risk-management contact, would not discuss the company’s safety procedures over the telephone. “Look it up on the Internet,” he said, and then hung up. He did not respond to an additional request for comment.

A South Carolina accident

One ammonia incident represents how quickly the pungent chemical announces itself, allowing those nearby to get away — and yet how stealthily it can kill.

In 2009, a hose ruptured as ammonia was being transferred from a truck to a storage tank at Tanner Industries in Swansea, S.C. A small amount, 100 to 500 pounds, vaporized, and a dense white cloud drifted over U.S. Highway 321, south of Columbia, the state capital.

Most people living nearby smelled the noxious chemical and escaped. Fourteen people complained of breathing difficulties or dizziness, according to news accounts.

Jacqueline Patrice Ginyard, a 38-year-old home-care worker, drove into the cloud. Officials speculated that the ammonia caused her car engine to conk out. She tried to escape.

Emergency workers found her body 10 feet from the car. The cause of death was ammonia poisoning, according to a National Transportation Safety Board report.

The hose being used was incompatible with highly corrosive ammonia and was labeled for use only with liquified petroleum gas. The NTSB said it had been used before to unload ammonia.

The U.S. Attorney in South Carolina indicted Werner Transportation Services for the negligent release of a hazardous pollutant resulting in death. The trucking company pleaded guilty and agreed to pay a $500,000 fine. OSHA fined Tanner Industries, based in Southampton, Pa., north of Philadelphia, $5,100 for safety violations.

Ammonia is easy to store safely, according to engineers, as long as the right equipment is used, equipment is kept in shape, and handlers are well trained. It’s kind of like storing propane in your backyard barbecue.

“If my propane tank rusts, it leaks, and that’s a problem and I have a possible explosion,” said Ronald D. Neufeld, professor emeritus of environmental engineering at the University of Pittsburgh. “An ammonia tank is a lot bigger, and a bigger explosion. … You must insist on inspections, monitoring and reporting.”

Reducing danger

One purpose of the Clean Air Act is to prompt companies to use fewer toxic chemicals and install safer equipment. Airgas Inc., an $8.1 billion company based in Radnor, Pa., appears to have done so.

Airgas Specialty Products in Palmerton, near Allentown, buys ammonia in bulk, repackages it in smaller containers and ships it to manufacturers by rail and truck. The EPA classifies it as a high-risk facility because of the large population that lives within its worst-case scenario zone.

Airgas acquired the facility in 2005 from a company that used large storage tanks to produce ammonia. Last year Airgas installed smaller tanks, according to spokesman Barry Strzelec, reducing capacity from 4,000 tons to 236 tons.

Previously, Airgas reported that a toxic plume could reach 660,000 people living within 21 miles of the facility. That was, by far, the greatest potential impact of any ammonia facility in Pennsylvania.

Since the changes, the potential impact is five miles around the plant. Strzelec would not say how many people live in that zone because the EPA has yet to accept a new risk-management plan the company submitted on Jan. 3. PublicSource used 2010 U.S. Census data to estimate that about 30,000 people live within five miles of the plant.

The company also installed sensors that detect ammonia leaks and activate a fogging system to suppress the gas. The new system is expected to be fully operational this month.

Strzelec said the change was made in “consideration of numerous factors, such as efficiency, our customers’ needs, and safety.”

Airgas has “significantly reduced the potential impact” of a big accident, Martin Wehner, president of Airgas Specialty Products, wrote in an email.

PublicSource is a NewsWorks content partner producing in-depth news coverage on Pennsylvania.

About this project: Reporters examined Environmental Protection Agency filings for 122 Pennsylvania facilities that use large amounts of ammonia, a chemical that the EPA classifies as extremely hazardous. Each report shows how many people could be affected in a worst-case ammonia leak.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.