The future of I-95: what is possible?

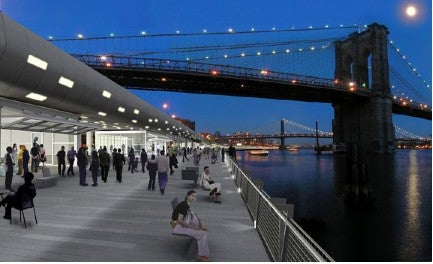

Metal cladding and bright lights civilize the highway underbelly in a plan for New York’s FDR Drive (City of New York)

By Matt Blanchard

For PlanPhilly

With concrete legs and a steel-truss spine, Interstate 95 appears to be an indestructible beast, an immutable fact of the Philadelphia waterfront that will stand between the city and its major river forever.

But according to the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, parts of the 35-year-old road will soon reach the end of their service life. Already, the agency lists some viaducts in South Philadelphia as “structurally deficient.”

In fact, much of the highway from Girard Avenue south to the Delaware state line must be rebuilt during the next 10 to 20 years. And since designing such projects can take six to eight years by itself, planning the future of I-95 must begin soon.

Were work to start today, PennDot officials say they would rebuild I-95 pretty much as it is now – a model of the 1960s-era highway design that most urban designers have since rejected.

This leaves Philadelphia facing a question: Should we allow the state to simply rebuild the highway we’ve got? Or should we try something radical?

“Years ago, people wouldn’t even look at these questions. They’d say ‘Forget about it.’” observes Ian Lockwood, a veteran traffic planner with experience on both coasts. “Today, so many cities are working on this, it’s refreshing… People should think ambitiously – start with the big ideas – and later we can back down to what we can do.”

This article is a gallery of six “big ideas” from other cities tackling their urban highway problem. Whether they’ve demolished, buried, built over or worked around their major roadway, each city was chasing the same goals: to re-stitch the urban fabric, restore connections to waterfront, lift property values, spur development and boost tourism.

_______________________________

PORTLAND: From highway to river park

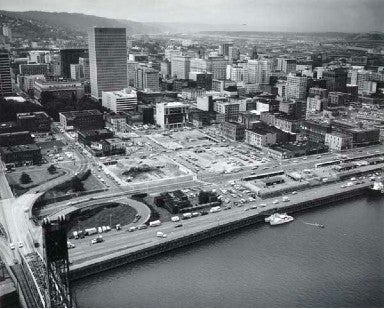

BEFORE: Portland’s waterfront was dominated by Harbor Drive in 1974 (www.portlandonline.com)

The American revolt against intrusive urban highways began more than three decades ago in Portland, Oregon.

That city ripped out a four-lane waterfront highway, the Harbor Drive, way back in 1974 – the very same year that Philadelphia started digging the concrete canyon for I-95 in Center City.

With the visionary leadership of Governor Tom McCall, the city defied the traffic planners, who predicted gridlock, and restored pedestrian access from downtown to the Willamette River.

For its bold planning in the 1970s, Portland got a spectacular 36-acre waterfront park with sloping lawns and public events. Named for Gov. McCall, the park remains the cornerstone of downtown redevelopment in that city today.

For Philadelphia’s bold planning in the 1970s, we got Penn’s Landing.

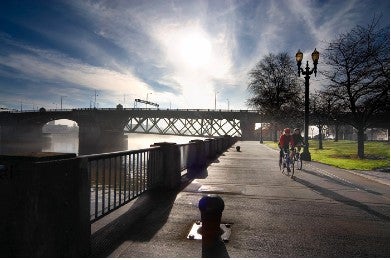

AFTER: No highway, no problem: Portland’s waterfront today (www.friendsforourriverfront.org)

AFTER: Cyclists near the Burnside Bridge in McCall Waterfront Park (www.portlandground.com/archives/2005/01/cyclists_near_b.php)

AFTER: Portland’s Waterfront Blues Festival in 2006 (www.waterfrontbluesfest.com)

_____________________________________

SAN FRANCISCO: From highway to boulevard

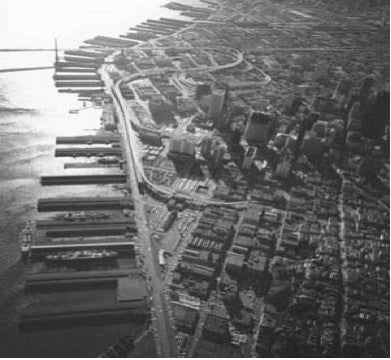

BEFORE: The Embarcadero Freeway in 1969 (www.preservenet.com)

Voters in San Francisco actually rejected a referendum to tear down the Embarcadero Freeway in 1986, egged on by newspaper columnists and traffic planners who feared gridlock should the 1.2-mile spur highway be demolished.

But on October 17, 1989, the magnitude 7.1 Loma Prieta earthquake seriously damaged the elevated highway, and as months passed, the predicted gridlock never materialized.

In 1991, the city demolished the freeway, spending $50 million to replace it with a street-level boulevard lined with palm trees. Today, historic trolleys bought from cities in the U.S. and Europe carry tourists between downtown and Fisherman’s Wharf.

Few mourn the lost freeway now that the Embarcadero is one of America’s finest waterfronts, with nearby property values jumping 300 percent, and two new neighborhoods, South Beach and Rincon Hill, rising on once fallow land.

Thirteen years later, San Francisco would do it again, demolishing much of its elevated Central Freeway to create Octavia Boulevard.

AFTER: Historic trolleys on the new Embarcadero (cyburbia.org)

___________________________________

SEOUL, KOREA: From highway to waterway

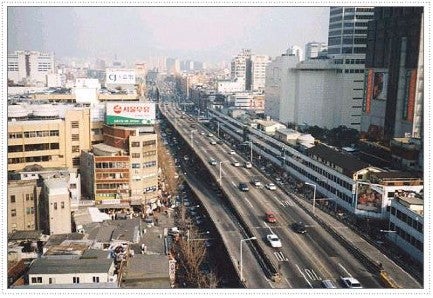

BEFORE: Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon Freeway before 2000

In 2003, Seoul Mayor Lee Myung-bak decided to demolish the one freeway that cut through the city center. He made no plans to replace it. His purpose for this dramatic act was to restore the historic Cheonggyecheon stream buried by highway-builders decades before.

Ripping out a major road to daylight a small stream – at a cost of $900 million – is the sort of plan that would get most American mayors run out of town.

But Myung-bak’s restored Cheonggyecheon is no humble stream. Opened to the public is 2005, it’s now an urban dreamland of waterfalls, walking paths, and playgrounds. The water’s journey through downtown Seoul is by turns intimate and magnificent, creating one of the finest city spaces in Asia.

AFTER: The Cheonggyecheon River restored in 2005 (www.spacing.ca)

For more images, see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheonggye

_____________________________

BOSTON: From highway to greenway

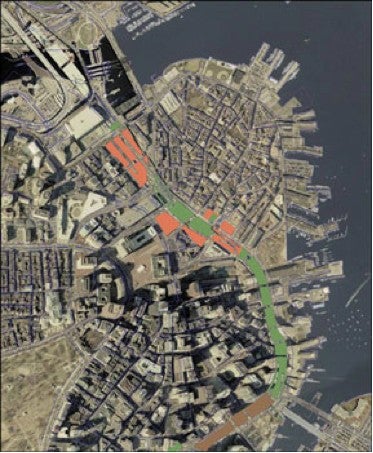

The Big Dig creates 23 parcels over Boston’s Central Artery (photo: Ross Adams and Stephen Smith, ocw.mit.edu)

On its way to becoming a stunning success, Boston’s ambitious “Big Dig” has drawn scorn as a boondoggle. Originally priced at $2 billion, the project’s $15 billion price tag is said to have federal highway officials muttering “never again.” And while the project cost galls, the project itself has killed: a motorist was crushed when a 20-ton panel fell from a tunnel ceiling in 2006.

But the Big Dig promises immense benefits for Boston. The downtown wing of the project replaces the unsightly elevated I-93 Central Artery, which was due for replacement, with a buried highway.

By sinking the highway into tunnels, the Big Dig opened 23 development parcels in a curve around the downtown. Collectively known as the Rose Kennedy Greenway, the corridor will weave new lawns, gardens and plazas around new mixed-use buildings and a number of proposed public buildings, including the Boston Museum designed by Moshe Safdie and the New Center for Arts and Culture, by Daniel Libeskind.

Developing these over-highway parcels has been tough. Plans by the Massachusetts Horticultural Society to build a majestic winter garden collapsed in 2006. Before that, park designs for other greenway segments drew little public enthusiasm.

In time, however, new pieces of city fabric will rise on those 23 parcels. Delays and doubts are likely to fade as investment money pours into downtown Boston.

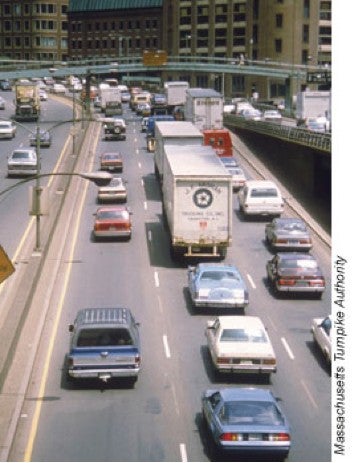

BEFORE: The elevated Central Artery

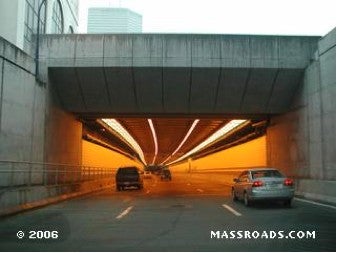

AFTER: The Central Artery Tunnel

__________________________________

LOUISVILLE: Working around the highway

Louisville frolics along the Ohio River despite Interstate 64 (www.louisvillewaterfront.org)

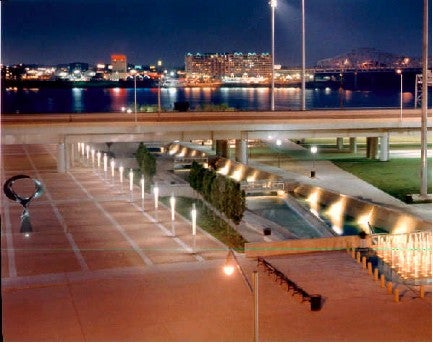

In Louisville, Kentucky, a 55-acre wasteland of industrial properties – as bad as anything along the Delaware – is now an award-winning public space, the Louisville Waterfront Park. It’s a striking example of how to work around an elevated highway.

The park features cascading fountains, crowded playgrounds, jogging paths and rolling lawns that slope down to the Ohio River – even though a tangle of highways snakes directly overhead.

This unlikely marriage of Frederick Law Olmstead and Robert Moses required the relocation of a highway ramp, but otherwise the park and highway live in peace. Over 1 million visitors frolic here each year as I-64 speeds overhead. They attend concerts on the Great Lawn, splash in the 900-foot chain of fountains, and board the Belle of Louisville riverboat down at the wharf.

A 30-acre Phase II will include landscape features like a “spiral hill” and a new pedestrian bridge across the Ohio River built on the pilings of an old railway viaduct.

Well-lit and well-kept, the Great Plaza slides right beneath the highway viaduct.

A curving edge provides a simple connection to the water.

______________________________________

NEW YORK: Reclaiming the elevated underbelly

The FDR viaduct becomes the centerpiece of East River esplanade

(New York City Department of City Planning)

Though it hasn’t been built yet, a visionary plan from the Big Apple could hold lessons for our own City of Brotherly Love.

On the Lower East Side of Manhattan, a team including London architect Richard Rogers and New York-based SHoP Architects conceived a number of eye-catching improvements to civilize the elevated FDR Drive. They would re-clad the highway’s underside in attractive metal panels, add a snazzy lighting scheme and build pavilions for various activities beneath the road.

The architectural renderings are striking – and a little hard to believe. They show a highway underside that’s as brightly lit and well-swept as a suburban mall, despite thousands of noisy, sooty cars and trucks rumbling overhead.

Here in Philadelphia, with a lower population density and ample vacant land, construction beneath highways would seem unlikely. Yet architects like Denise Scott Brown have suggested the use of similar underbelly makeovers in strategic places along I-95 to create welcoming gateways, or “outdoor rooms,” that would encourage foot traffic from the neighborhoods to the river.

View the East River Waterfront Study for Manhattan at http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/erw/index.shtml

Matt Blanchard is a former reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer who now teaches at the University of the Arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.