Casino fight goes to council

By Matt Blanchard

For PlanPhilly

Philadelphia City Council began consideration of strident anti-casino laws on Wednesday, one of which would make casinos illegal inside city limits, and all of which could put the city on a collision course with the state and further delay gaming in Philadelphia.

The eight proposed ordinances introduced by Councilman Frank DiCicco, whose 1st District includes the SugarHouse and Foxwoods casino sites, range from an outright ban down to zoning code tweaks that would force casino developers to seek zoning variances from the city. Most would seem to fly in the face of State Assembly legislation mandating two casinos in Philadelphia at the precise waterfront locations determined by the state Gaming Control Board last year.

“We all know the [casino] operators will challenge these ordinances in court,” DiCicco told a packed council chamber. “We might lose some of these challenges, but so be it… This process has been screwed up from the start, and none of us has had a voice. It’s time we took back that voice, and that’s what this legislation is all about.”

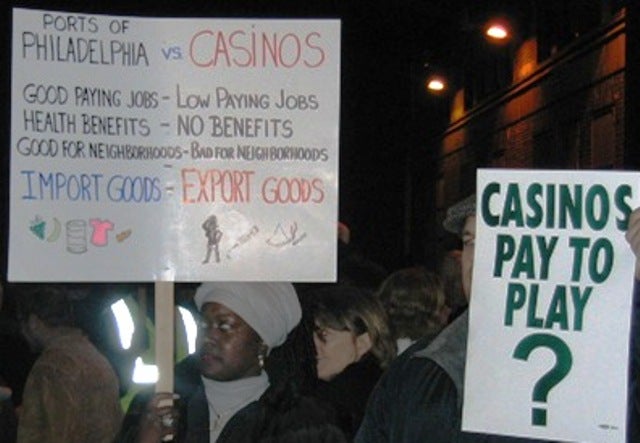

Like a sudden valve opening on a high-pressure pipe, Wednesday’s hearing vented a torrent of ideas and opinions from every side of the debate. Brigades of anti-casino activists, simmering for months over what they consider an undemocratic approval process, took turns at the microphone with casino executives and city officials who extolled the economic benefits of casino revenue.

Eight hours later, the hearing before Council’s Committee on Rules ended with no vote taken. Council president Anna Verna announced the hearing would be continued Wednesday, March 14th at 1 p.m. At that time, a vote to move some or all of the proposed ordinances out of committee would put the issue before the full Council.

In related news, Verna also announced that a 27,000-signature anti-casino petition submitted by Casino Free Philadelphia had been accepted by council. On Friday, March 2nd at 10 a.m. the council’s Committee on Law and Government will hold a hearing on the petition’s purpose: to put a casino referendum on the May 15 ballot.

DiCicco’s Attack Plans

If passed, DiCicco’s proposals would erect a series of roadblocks for casino gambling in Philadelphia. The councilman described his proposals as a “Plan A” followed by plans B, C and D, for use if plan A should be overturned in court.

Plan A is an ordinance prohibiting the “erection, construction, alteration, or use of licensed gaming facilities.” This blanket ban would allow no appeal and no zoning variances.

If that fails, DiCicco’s Plan B is an ordinance that would alter the city’s new gaming friendly zoning designation, Commerical Entertainment District (CED), such that the very casinos it was designed to accommodate would no longer be permitted. Casino operators would have to appeal for a variance, allowing citizens to challenge the variance. It would also forbid the erection of temporary gaming halls.

Plan C is an ordinance that would force the creation of a Neighborhood Improvement District covering the area of any new casino before that casino is built. DiCicco claimed this would give neighborhoods more power, describing the ordinance as a “de facto referendum process for nearby residents.”

Plan D would make gaming facilities a “regulated use” in the zoning code, again forcing casino operators to win city approval.

Other ordinances seek to rezone casino parcels to zoning designations that do not allow gaming, and to restrict check-cashing and related businesses from a 1000-foot radius around any casino.

What follows are highlights of the debate. In attendance were council members Anna Verna, Jim Kenny, Darrell Clarke, Bill Greenlee, Blondell Reynolds-Brown, and Dan Savage.

City officials skeptical

City Solicitor Romulo Diaz Jr. spoke first, reminding council members that “gaming represents a historic revenue opportunity.” Each year, gaming would funnel $5 million to Philadelphia schools and between $20 and $25 million to the city’s general fund, in addition to allowing a 13% reduction in the city wage tax. Diaz said construction of the facilities would employ 1,000 in the building trades, who would take home a combined $34 million in wages. Once open, the casinos would employ 2,000, mostly from Philadelphia.

Diaz suggested fighting the casinos with “unreasonable” legislation would “inevitably” be shot down by state courts, and would leave the city with less power to shape the casinos.

“We believe it is appropriate for the city to retain local zoning control, but we can only exercise our authority in a manner that compliments, rather than thwarts, the state’s plan,” Diaz said.

Thomas Chapman then reported that the City Planning Commission had considered DiCicco’s proposals the day before and recommended that Council reject all but one of them, the restriction on check-cashing operations. Chapman sought to defend the new CED zoning designation from DiCicco’s tinkering, arguing that it was the city’s best effort to retain zoning power over casino developments. He also announced that Mayor Street would be launching a series of “community engagements,” or public hearings on the specific casino proposals.

DiCicco fired back: “For the City Planning Commission to take the position that we should simply roll over because we’ll lose in court, I think, is simply irresponsible.”

Sugarhouse Speaks

Dialogue has been in short supply ever since irate neighborhood associations up and down the river launched a boycott of negotiations with casinos. Yesterday, executives from Sugarhouse and Foxwoods got a chance to make their case.

Sugarhouse casino president Bob Sheldon described his $550 million project on the Fishtown riverfront as an exciting destination with 3,000 slot machines and an accessible public promenade along the water.

“For the first time in a generation, for residents of Fishtown, the Delaware River will no longer be something they can see but not approach,” Sheldon said.

Sheldon said Sugarhouse would produce more than $1 billion in tax revenue over the first five years, and create 1,100 permanent and high-quality jobs at an average wage of $40,000, when benefits are factored in. He also argued against those who predict a rise in petty crime once gaming arrives: “Let me make it clear that if there is an increase in crime around our facility, we are not going to be successful as a business.”

Finally, Sheldon struck back at the widespread belief that the community has been shut out of casino design, listing ten public meetings at which Sugarhouse staff sought public input – all before community groups pulled out of negotiations. “These public meetings were well-publicized and well-attended and do not include dozens of private meetings we had with other community leaders,” Sheldon said.

Riparian Rights

Sugarhouse executives revealed their project could be chopped in half in the event that the state does not grant them use of the riparian lands on the site. Riparian is a technical term for land at the river’s edge and on the riverbed over which the state maintains legal control. At the Sugarhouse site, company executives said a loss of riparian rights could eliminate 11 acres from the 22-acre site. Should this happen, they said, the casino would occupy a building along Delaware Avenue, but all the waterfront public spaces in the plan would “disappear.”

Would that be a bad thing? The Rendell administration is currently reviewing the state’s process for awarding riparian rights, leaving future policy uncertain. But city council candidate Matt Ruben, speaking later in the session, argued that withholding riparian rights would allow the creation of a publicly-owned promenade along the river.

Foxwoods Faces the Traffic

Foxwoods casino executives Jeff Rottwitt and William G. Schwartz spoke next, sharply denouncing the ordinances as egregious acts of spot zoning. They noted that one bill would rezone just their site in South Philadelphia for homes.

“These bills are poorly thought out, or not thought out at all,” said Rottwitt. “Most legal scholars would agree these aren’t legal, and the State Supreme Court has spoken on this.”

Opposition to Foxwoods has been centered on the thousands of cars it will attract to an already congested stretch of Columbus Boulevard. Rottwitt took the topic head-on, however, promising to pay for road improvements that would not only reduce Foxwood’s impact, but make an improvement over current conditions.

“We’ve come up with a series of improvements, including additional left-hand turning lanes and improved signalization that will improve existing traffic flow by 32 percent,” Rottwitt said. “People should be skeptical. People should wonder if this is propaganda. But we’d like the opportunity to sit down with people and explain it.”

Councilman Kenny argued that Foxwoods traffic could strangle the Port. “I’m worried our shippers might say: ‘You know what? I can’t get my cargo in or out of the Port of Philadelphia, because of all the traffic.’”

Kenny said a proposed new ramp to I-95 – itself a controversial issue – was at least 5 years away. He said traffic congestion in the interim “will be a nightmare for you and a nightmare for us.”

Rottwitt returned that there would be no interim: Foxwoods will not be building a temporary slot parlor, and the permanent structure will not be open during the two years it will take to make road improvements.

Casino Free Philadelphia

Fresh from gathering 27,000 signatures to get a casino referendum on the May 15 ballot, the anti-casino group Casino Free Philadelphia flew Connecticut anti-casino crusader Jeff Benedict in to unload his broadside against casinos in general.

Benedict, a former president of the Connecticut Alliance to Stop Casino Gambling, described Connecticut’s experience with gambling as a false seduction followed by lasting regret.

“Our two casinos currently generate 80,000 automobile trips on an average day,” Benedict said. “That impact comes on like a light switch. It’ll arrive overnight.”

Benedict attempted to debunk several pro-casino claims, including the suggestion that casinos produce “spin-off” jobs in nearby restaurants and hotels.

“Casinos want to capture the customer. They want to keep him inside,” Benedict said. “We [in Connecticut] bought that line. It’s been 15 years and the spin-off still hasn’t happened.”

Benedict also attacked the notion of casinos generating revenue. He said that even though Connecticut draws a whopping $2.4 billion in annual revenue from gaming, the state has not moved to build more casinos, but has instead banned all new construction. The reason? Benedict said state officials realized that hidden impacts to businesses, infrastructure, social stability and public safety outweighed the obvious cash benefits. Connecticut, he said, has had to open 17 gambling addiction counseling centers

Benedict grew graver still when discussing Philadelphia, where the casinos will not be in a rural location, but within walking distance of neighborhoods. He predicted the emergence of a “new class” of casino poor, afflicted with bankruptcy, gambling addiction, property foreclosures and petty crime.

Fighting for the Port

Longshoreman’s union vice president Jim Paylor continued his campaign to win respect and expansion space for the Port of Philadelphia – and the 45,000 jobs he says grow out of his industry.

While casinos offer as much as 2,000 new jobs, Paylor argued that the global shipping business is about to bestow far better-paying jobs on Philadelphia’s port facilities, as the Panama Canal is widened and ports like New York run out of space.

“We now handle 300,000 containers a year,” Paylor said. “I’m talking about a scenario where that number is 3.5 million containers.”

While casinos offer the city as much as $30 million in tax revenue each year, Paylor reminded council his industry generate $43 million, and will be threatened if casino traffic ties up trucking routes, and a casino-inspired building boom starts eating up valuable industrial land.

“What I am saying to you councilmen, is that a well-designed plan doesn’t have to hurt anybody,” Paylor said.

Fact and Fiction

Among the citizen voices heard in council on Wednesday, Rene Goodwin of the Pennsport Civic association launched the sharpest attack with a rapid-fire listing of various “Fictions” about casino developments, and the “Facts” that are hidden behind them.

“Fiction: Casinos generate revenue,” Goodwin said. “Fact: They don’t generate anything. They take from other sources by drawing in persons to gamble with monies that would be used for food, clothing, rent, bills, or that would be spent in local businesses.”

“Fiction: It’s a done deal. Fact: Maybe not.”

Other resident opponents included A.J. Thompson, Matt Papajohn and Matt Ruben, who is running for city council. Ruben launched an impassioned defense of DiCicco’s eight proposed ordinances, likening the casino licensing process to the “fruit of a poisoned tree.”

“These bills will stop this process in its tracks,” Ruben said. Casinos are not private development. They are public policy. They were legalized to raise revenues and therefore they should be subject to public input as much as any public policy that affects daily life.”

The Convention Center at Stake?

As the session moved toward conclusion, six highly placed regional tourism officials testified in favor of the casinos, not simply as tourist attractions in their own right, but as a crucial source of funding for the expansion of the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

Ahmeenah Young, executive vice president of the Pennsylvania Convention Center, reminded council members that the convention center is probably the most important economic generator to arrive in the city for the last 20 years.

Bill Walsh of the Philadelphia Hotel Association argued that casinos would boost his industry, and that expansion of the convention center should not be put in jeopardy.

“It’s absolutely essential,” Walsh said. “And that expansion is primarily funded by gaming.”

Jack Ferguson of the Pennsylvania Convention and Visitors Bureau, added that the two casinos would “expand our nightlife offerings and develop the waterfront to become a vibrant destination.”

Councilman Kenny was doubtful: “If the goal of the casinos is to maximize the machine revenue by keeping people in front of them, how does that improve our nightlife in Old City?”

Tourism officials countered that convention guests often stay for several days, and choose cities based on the diversity of nearby attractions. The casinos would make an attractive after-dinner event, said Ferguson.

DiCicco challenged the notion that the convention center would not be expanded without casino revenue, or that not having casinos will hinder the convention business.

“As I understand it, casinos are not a deal-breaker for the convention center,” he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.