Should we be paying organ donors?

Listen

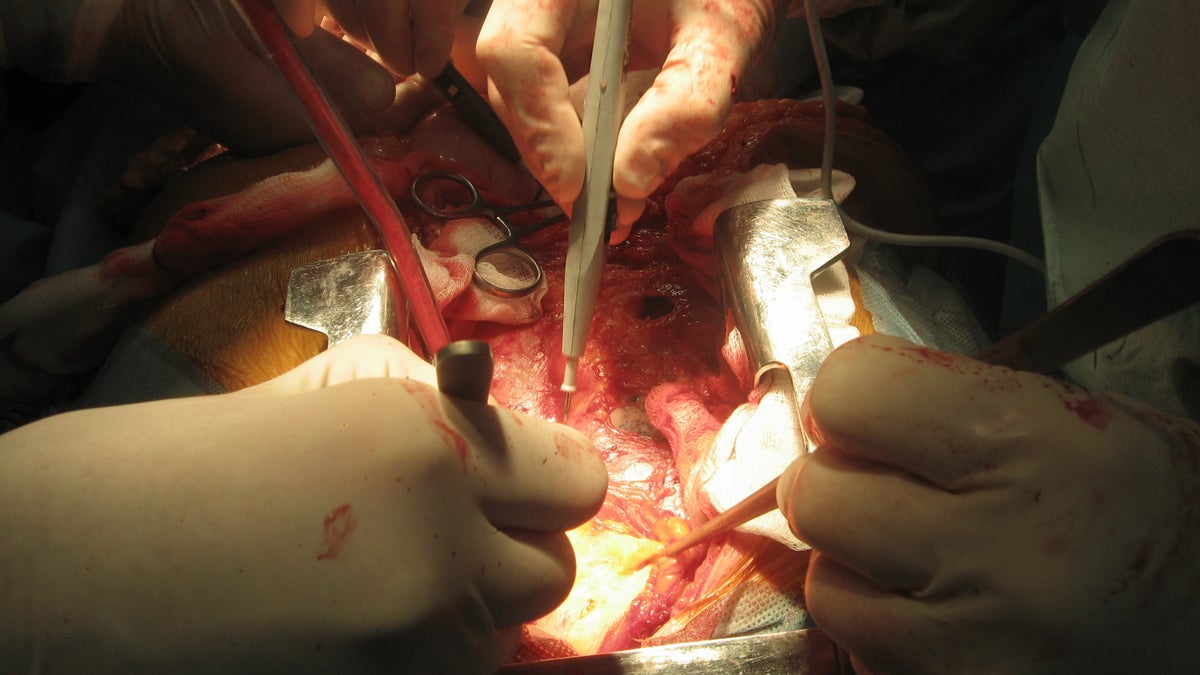

(Shutterstock Image: http://shutr.bz/1gtTMEX)

The idea could shorten waitlists, but violates a long-held taboo.

After a routine check-up in August 2004, Sally Satel’s doctor called with unexpected news. Despite feeling in good health, routine lab work came back showing she had rapidly failing kidneys.

“He was quite shocked, and he repeated it, and it was the same dismal result,” says Satel, who was 48 years old at the time. “And then I knew what faced me.”

Satel, a psychiatrist and lecturer at the Yale School of Medicine, had end-stage renal disease, which meant she’d require years of dialysis while she inched her way up the organ transplant list. The alternative was securing an organ from a friend or relative.

“It was a very, very difficult and, frankly, unusual time. You are in a position where you’re asking people for a body part,” she says.

After several false starts–what she calls near-transplant experiences–an acquaintance on the other side of the country proved a willing match. The transplant was completed in March 2006, with the donor receiving nothing more than Satel’s profound gratitude.

But the experience left Satel, who is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, frustrated with the country’s organ transplant system and organ shortage. More than 120,000 people are currently waiting for an organ, roughly triple the number from two decades prior. According to federal government, 22 people die each day waiting for transplants.

“The scope of the problem is tremendous,” she says.

A selfless act

In 1984, a law called the National Organ Transplant Act laid out the modern system by which donors are wait listed and organs procured for donation. The legislation put a strict ban on compensating donors, although reasonable reimbursements for things like travel and housing were exempted.

Altruism, the idea that people should and will donate out of the goodness of their heart, was placed at the core of the American organ system. Satel believes the statistics prove it hasn’t been enough.

“I can understand why we started that way in 1984, but three decades later, it is clear that it is a qualified failure,” she says.

Satel is calling for an end to what has long been seen as taboo in the field. She’s a leading advocate for a pilot program that would give living donors–people who give a kidney or portion of their liver–a non-cash payment of $50,000. The money would be in the form of a tax credit, scholarship or 401k-style contribution, but it wouldn’t come from the recipient. Instead, the federal government, through Medicare or Medicaid, would distribute the money. (The entities, in theory, would save money overall by decreasing the number of members on dialysis.)

The idea of a trial program has its backers.

“We have to stop writing about it and actually do it,” says Dr. David Goldberg, who runs the Living Liver Donor Program at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia.

He says financial incentives aren’t just about attracting more donors. Instead, its about compensating the friends or relatives who are already interested, but can’t go through with it because of money problems.

Donating an organ often means missing a fair amount of work, and while there are programs that do provide limited reimbursement for donors, the financial math still doesn’t work out for many families.

“There have been times where we have decided that we would not go forward because we could not risk putting a potential donor and his family and his kids, who are living paycheck to paycheck, at risk of going to debt and losing their home even,” he says.

Bought and sold

For others in the transplant system, the concept of significant financial reward raises serious red flags.

“It becomes more of a business transaction than a gift, and there is a big social change when you talk about things like that,” says Howard Nathan, longtime CEO of Gift of Life, an organ procurement organization in Philadelphia.

In 1994, he played a major role in crafting what remains a groundbreaking state law. Pennsylvania Act 102 awarded a stipend of $300 to the family of a deceased organ donor, but rather than going directly to relatives, the money would go to a funeral home to pay for burial expenses.

But just before being implemented in 1999, state officials got cold feet over concerns it violated the federal ban on compensation, and they pulled the plug.

“I guess we were pretty naive,” says Nathan. “I think the idea was, we thought this made good sense.”

Nathan still likes the idea of a funeral voucher (and notes the law is technically still on the books) because it acknowledges the family’s contribution to society. It maintains the altruistic system, but one with a formal ‘thank you’ gift from the government.

The idea of a payment as large as $50,000, however, doesn’t sit well with Nathan, in part because it could result in a system by which many more poorer donors lured by the payment give organs to wealthy recipients.

“Could a trial take place and could the trial take place so that people have some sort of rewarded gifting? I might be in favor of that. But I think the key is when it gets to be a significant amount of money, it really is repugnant,” he says. “You are buying and selling organs.”

There’s a line here between what’s expressing gratitude, and what comes off as a bribe. And for each person, that line gets drawn in a different place.

Sally Satel has laid out her position, and says she’ll continue pressing for a pilot program to test an incentive system.

“It has just been so ingrained in the culture of the transplant community that altruism is the sole legitimate method for giving an organ,” she says. “That’s what all the campaigns and educational efforts have been built around, and it is a beautiful sentiment: I’m talking to you because of it.”

But a decade after her own transplant, Satel believes that we can no longer rely solely on altruism. “It’s just simply not enough.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.