Solving mysteries key to next generation of computers

Listen

If researchers can successfully braid quits

A missing physicist and the puzzling particle he hypothesized hold the keys to quantum computing.

While we all oooh and aaah over the latest tech gadget, some of the biggest technology companies in the world are quietly chasing the holy grail of the information age. Quantum computing. They’re hoping to build a computer so powerful; it would do everything from solving incredibly complex mathematical riddles to sorting through the universe of data collected about us. The first challenge is getting the quantum bits to dance how we want them to.

Before getting too high-tech, let’s go back to 1938. A brilliant physicist, an Italian named Ettore Majorana, withdraws all his money from a bank and boards a boat. Then, somewhere between Palermo and Naples, he vanishes without a trace.

“That’s a million dollar question. I wish I would have an answer. Majorana disappeared, and a lot of theories, a lot of speculations have been made. What can I say? The answer hasn’t been found.” says fellow Italian Lorenza Viola, a Dartmouth College physics professor. She researches what’s come to be known as the Majorana particle.

The year before his disappearance, Majorana published a paper theorizing a revolutionary concept: that there was something out there that could be both a particle and its own anti-particle at the same time. A quasi-particle floating around in the subatomic world.

Decades later, scientists have come to believe these properties would make it a good base for a quantum computer.

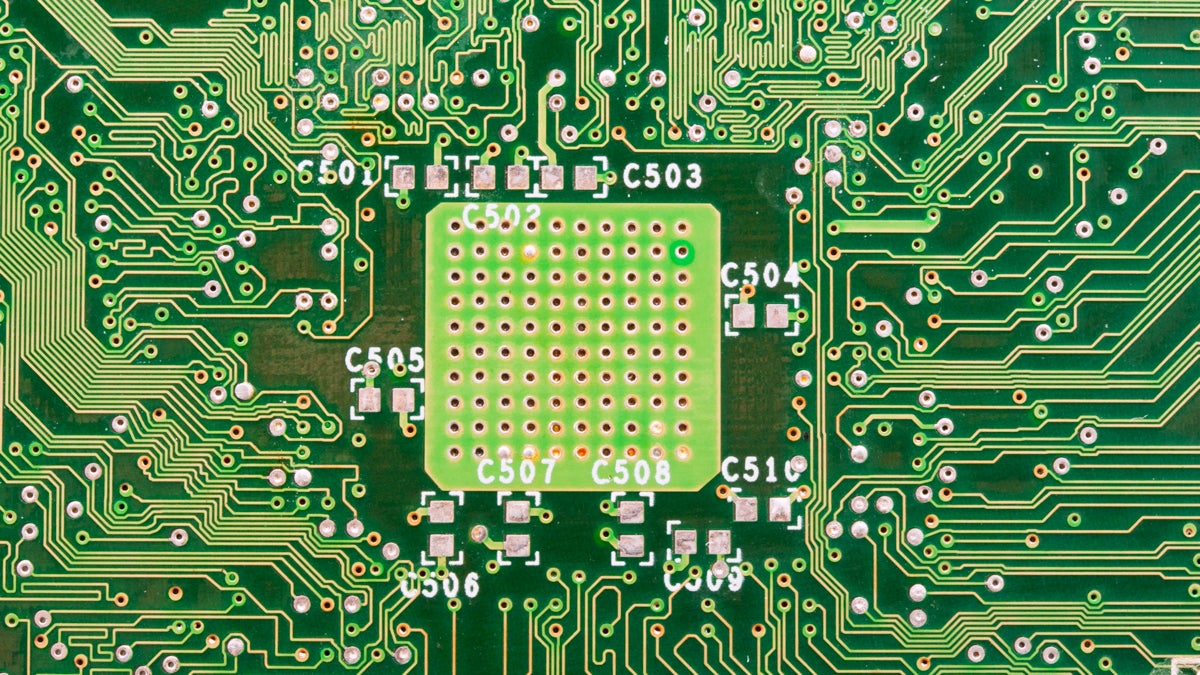

Today’s digital computers are built around bits, all the 0s and 1s that run our machines.

The idea behind a quantum computer is that instead of bits, you have qubits, which can be a 0, or a 1, or basically both at the same time.

The problem is, so far, the qubits researchers have identified keep falling apart when put into action. Viola says the Majorana, because of its peculiar qualities, may hang together.

“The fact that once created, once identified, it would be harder to destroy them, and so they would be intrinsically more stable, more protected, and so potentially more useful in a qubit. I don’t know if it makes sense, but, that’s the idea.”

At this point, the Majorana is still mostly theory. In 2012, a team of Dutch researchers came the closest to proving its existence. But if someday finally harnessed, researchers will face a second challenge: getting it to do the computer operations they want it to.

University of Pennsylvania physics professor Charles Kane says that will require a concept called braiding. The Majorana particles get braided together into patterns to maximize their power.

“What I want you to imagine is a square dance party where the two-dimensional plane is the dance floor, and the particles are the dancers,” he explains. “And the caller tells you to do a dos-e-do. That means you move around your partner. The way that a quantum computer accomplishes a computation is by making the quasi particles dance around each other.”

Huge sets of data get tossed into the qubits, which dance and compute and then spit out the answers. Math problems that would stump the computers of today could be worked out in short order, including factoring numbers with hundreds of digits.

Professor Kane says right now, researchers are still at the early stages, working to tame the systems. “It is a very difficult problem. You have to understand your materials and you have to have control over them, and that’s requiring real state of the art technology.”

And that requires big money. Companies like IBM, Microsoft and Google are pouring tens of millions of dollars, if not more, into the field. Practical applications may be years off, but a working machine could advance encryption technology, or drug research, or any other area where big data holds answers.

“It is a risky venture, but if you can make a quantum computer, then you can do something that other computers can’t do,” Kane says.

That’s got companies and academics like Dartmouth’s Lorenza Viola still combing over the physics Ettore Majorana first put forward 75 years ago before his mysterious disappearance.

“I think if he could see us, or somehow be here, he would be very pleased because certainly he has left a big legacy,” says Viola.

And who knows? Maybe in another 75 years, Majorana will be a household name.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.