Local activists call for an end to street harassment

ListenHave you been the target of whistles and catcalls by strangers on the street? You’ll want to hear how these artists and activists are fighting back.

Depending on where you live or how you get to work, maybe it’s been awhile since anyone yelled “Yo, Shorty” at you from across the street — or hissed “Hey, Ma” as you walked by.

Sometimes those callouts and come-ons turn aggressive.

Holly Kearl founded the non-profit group Stop Street Harassment.

According to her website, street harassment is “any action or comment between strangers in public places that is disrespectful, unwelcome, threatening and/or harassing and is motivated by gender or sexual orientation.”

“For women who have to hear [these calls] a lot, it just gets annoying,” Kearl said.

She’s working to make sure women and girls feel safe in public spaces.

“That’s something that men are afforded, the luxury of walking places without other people approaching them and telling them how they look, or telling them to smile or asking them for their phone number,” Kearl said.

Activists set aside the first week in April each year to have a national conversation about wolf whistles, catcalls and awkward stares from strangers. They say those actions are not truly come-ons at all, but acts of intimidation.

Kearl says teenage girls in particular struggle with catcalls that escalate to questions like “Where are you going?” or “Can I come with you?” That can feel threatening, she says, even if a man doesn’t intend to take those questions any further.

“We don’t know which men are going to take it further,” she said.

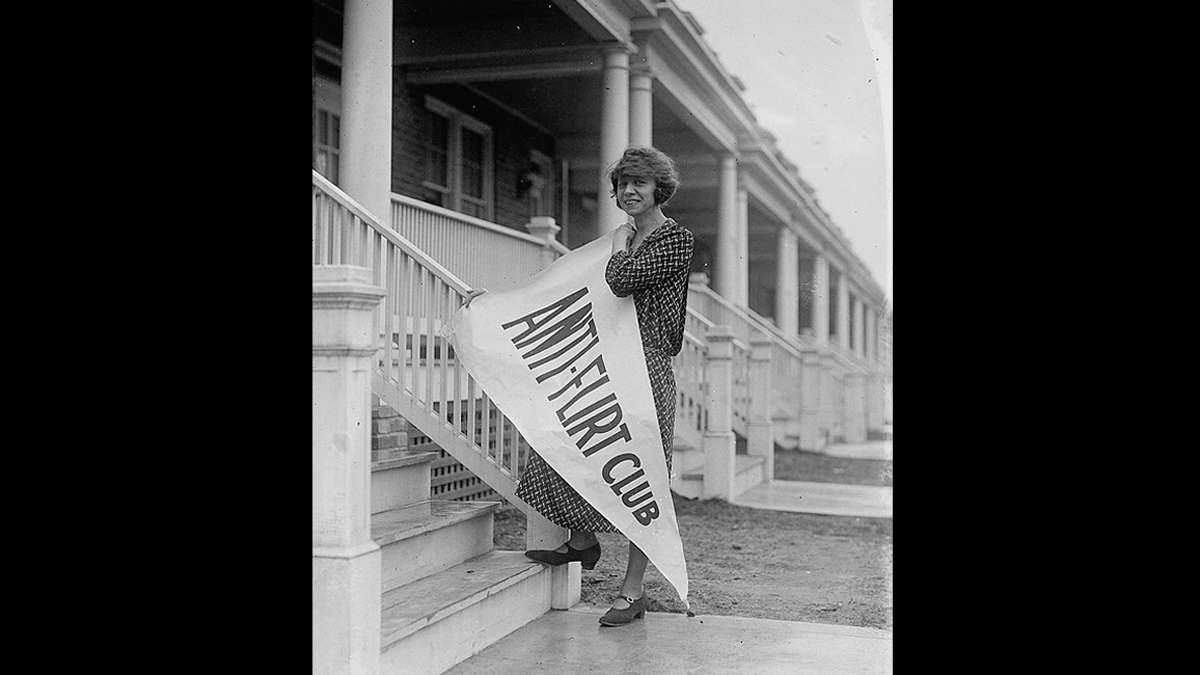

Policy ideas to stop street harassment have evolved, but early on, one solution was to simply separate women and men. In 1906, the Women’s Municipal League in New York City proposed a ladies-only commuter train to protect women from the ‘fearful crushes’ of licentious men. And in parts of Japan — today — some rush-hour trains are single-sex.

Back in the early 1900s, the New York City debate was heated in the editorial section of local newspapers and magazines. Opponents sneered and called the plan supporters “men haters.”

“I’m opposed to it. I don’t think our New York men are such beasts that we can’t sit in the same car with them. I like men,” Mrs. Lillie Devereux Blake, president of the Legislative League, was quoted as saying in the New York Times. “I think it would be most unpleasant if we had a car all to ourselves.”

Today’s anti-street harassment activists are sometimes also dubbed “man haters” — but Holly Kearl says she considers men allies in her work.

She wants to create a common definition for street harassment but is up against some pervasive — and conflicting — ideas about what behavior is acceptable. Take Saturday morning cartoons. For example, remember Pepé Le Pew?

“That skunk would chase that cat around, and she was always trying to get away from him,” Kearl said. “It’s like: Oh, ha ha— that’s funny. But she wants to get away from him. She should be able to get away from him.”

Anti-street harassment activist say their work doesn’t mean men and women can’t speak with each other outside. But Kearl’s advice to men who want to connect with women: Compliment a woman’s ability — not her appearance.

Kearl also suggests that men reserve their compliments for the women in their lives, who they actually know.

A public health problem?

Beth Livingston, an assistant professor at Cornell University, usually studies gender issues in the workplace but recently worked with the activist group Hollaback to review the collected stories of women who’ve experienced street harassment.

She noted some big emotional red flags beyond a quick flash of anger towards the perpetrator.

“There was a lot of fear, a lot of anxiety,” Livingston said, “a lot of people who described changing their behaviors and losing sleep because they knew they were going to have to walk by the same people every day on their way to work, on their way to school.”

For women who experience it frequently, street harassment is a stress that can accumulate, Livingston said.

“In the same way that having a sick child — or family member — for a long time can wear on you and build up stress and then your own health is then put at risk,” she said.

It’s still an open question whether street harassment is a public health problem. When you search health research databases there are few studies or even mentions of the term “stranger harassment.”

Several years ago, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention added questions about stranger harassment to one of its national surveys. Livingston says that leadership may encourage more public health professionals to consider street harassment a topic for study.

Community response

Hollaback is among the national groups trying to document where and how often street harassment happens. Activists are also using social media to give women a way to respond to street harassment — safely.

Locally, HollabackPhilly just posted a fresh batch of transit signs with anti-street harassment messages.

The feminist group Pussy Division has been out around town stenciling its own messages.

An artful approach

Others are talking directly to men about what’s acceptable.

“Having a man tell me that I’d be prettier if I would smile, or ask me to give him a smile makes me feel like I’m outside to entertain him,” said, New York artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh.

She attended Philadelphia’s University of the Arts and was a lead on a city mural dedicated to the music group The Roots. She created a series called “Stop Telling Women to Smile.” The posters include captions such as “Critiques on my body are not welcome” and “My outfit is not an invitation.”

“I wanted to talk about this because it’s something that I experience almost daily,” Fazlalizadeh said. “Before I started this project, I thought: Is it just me? Am I the only one that gets upset about this when it happens to me?”

The artist has heard often that the artwork is anti-male but rejects that opinion.

“It’s in no way anti-male at all,” Fazlalizadeh said. “It’s for women who experience — this who would like a voice, and it’s directed toward men to stop doing this behavior if that’s what you are doing.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.