Ghost forests signal what’s to come due to accelerating sea level rise

Listen

Ken Able

On an unseasonably warm December day, in a pristine corner of Southern New Jersey, near Egg Harbor City, Rutgers professor Ken Able prepared kayaks for a day of exploring the marshes. He stood checking the conditions from an unpaved, puddle-pocked road that dead-ended in water.

“This area is unique in New Jersey and even for the East Coast of the U.S. because there are very few people living in the watershed,” Able said. “As a result, the water is very clean, there’s lots of undisturbed habitat.”

The marsh, a maze of natural and manmade streams cutting through vast stands of invasive phragmites grasses, fell as the tide receded. Able handed a paddle to Jennifer Walker, a Rutgers graduate student studying sea level rise. Able is a fish biologist, but he’s also a local that has spent years exploring New Jersey’s waterways; he had something to show Walker.

Walker and Able paddled on Jimmie’s Creek, out onto the Mullica River where the wind turned the water choppy and the steering wobbly, and then they ducked again into a smaller, more protected stream called Big Creek.

As they paddled, the tide fell further and Able started pointing out tree stumps just under the surface of the water. As the tide continued to fall, it became clear that another world was emerging, a past one, when a forest stood right where they now kayaked.

This is what Able wanted to show Walker, a historic forest peeking out of the marsh.

Rising seas drowned these trees.

Looking to the past to figure out the future

Called ghost forests, the stands of dead trees appear in two primary areas. In the first, where Able and Walker were paddling, the trees are completely submerged and the marsh has already taken over. Then, on the shore, stands a line of upright, bare, gray tree trunks – Atlantic White Cedars. The marsh is in the process of claiming these drowned, but still standing, trees.

“They kind of extend back until you reach the border of the living forest,” Walker explained, pointing to the green peeking through the dead trees.

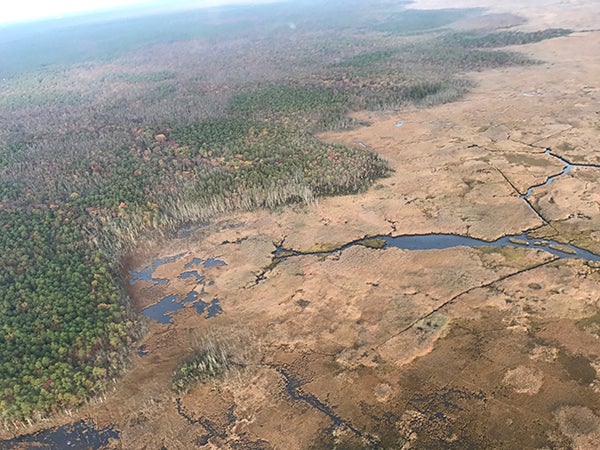

At one of Walker’s research sites, it’s possible to see trees completely drowned by the swamp, then the standing dead forest, and the live forest behind that. (Jennifer Walker/for WHYY)

As sea levels rise, water pushes up the water table underground and creeps further inland on the surface, inundating previously dry land. In the process, the water drowns trees and eventually forms marshes where forests once stood.

Walker’s job is to figure out how exactly that process unfolded in this part of New Jersey. She wants to understand the history of the marsh going back about 5,000 years, when it formed. To do that she’ll have to uncover when the trees died and how that relates to historic sea levels.

Seas rise when the climate warms and glaciers melt. The process of sea level rise – and fall – has happened repeatedly in the past. What may be unusual now is the rate of change. Sped up by human-caused climate change, everything seems to be happening very fast. Scientists are scrambling to better understand the complex relationship between climate and sea levels.

Walker is one of them.

“Since we want to figure out what kind of sea level rise we could see in the future we need to see how sea level responds to climate. So if you have a better understanding of that in the past, we can predict that for the future,” she said.

An aerial view of the New Jersey marshes showing the perimeter of dead forest on the shore. (Jennifer Walker/For WHYY)

Walker’s advisor, Ben Horton, said the idea is to paint a very clear picture of what happened in New Jersey, correlate that with research in other regions, and eventually clarify what we can expect to see around the world as the earth warms. If temperature and sea level rise together in a predictable fashion – for example, for each degree the temperature goes up, the sea level rises by X – that’s one thing. But if sea level begins to rise much more dramatically at a certain threshold or entire ice sheets begins to collapse, as seems to already be happening, it’ll be much harder to plan for.

“Sea level is a very sort of accurate barometer of climate change,” Horton said.

Happening everywhere

This part of New Jersey is an ideal place to study these processes. Because there hasn’t been much development here, the researchers can see how nature works with limited human interference. But Virginia Institute of Marine Science researcher Matt Kirwan said it’s happening everywhere.

“Nobody has summarized the effect of sea level rise on ghost forest formation across the U.S. or the Atlantic U.S. But it’s very clear that this process is occurring in most Atlantic coast estuaries,” Kirwan said.

He’s been studying marsh formation on an island off the coast of Virginia.

“Every storm, or high-water event that goes through, we see a few more trees that die. And usually new trees don’t get established once the adult trees have died,” he said. “Instead, the marsh just moves a little further inland.”

Kirwan said the rate of forest loss is accelerating. At his site, forest has been dying faster and faster every decade since the 1940s, something he attributes to the acceleration of sea level rise. Along the East Coast, the rate of sea level rise is even higher than the global average due to geologic and other factors.

“For people that live close to the coast, this is a depressing event. You’re talking about land that people have lived on maybe their families have lived on for several generations that was dry, usable farmland when their grandparents were alive. The big story here is that dry land is being converted to wetlands,” Kirwan said.

This isn’t theoretical for him. The marsh has swallowed up his grandparents’ land in Maryland. His grandparents grew strawberries until the 1940s and now that land is flooded twice a day, Kirwan said.

He’s trying to figure out how current rates of forest loss compare to forest loss during similar, historic episodes of change. He’s also trying to figure out whether the young marshes protect coastlines from storms as well as the older marshes being overtaken by ocean.

Nowhere to go

Back on land in New Jersey, Walker said everywhere she goes along the coast now, she sees these ghost forests. “I grew up near this area, close to the coast, going to the shore, so I feel more connected to the issue of sea level rise in particular,” she said.

She and Able drove to a cut of road several miles from the creek. Behind where she parked, stretched a swampy inlet, fallen logs criss-crossing the bottom. In front of her, Able, the Rutgers professor, pointed to a hem of standing ghost forest and then the live trees.

“So we’re right in the middle of the process here, you know,” he said looking around. “How old are those that aren’t standing? How old are those that are dead and standing? And then how about the live ones that are standing as well?”

“Here, where you have this nice transition right, live to dead, you should be able to match up the cores without too much trouble,” Walker said.

Jennifer Walker taking a core from a dead tree. (Irina Zhorov/The Pulse)

She marched into the ghost forest in her waders to take cores from the dead trees. She’ll use the cores to date the trees and start putting together a timeline of marsh formation in the area.

One of the cores Jennifer Walker took from a dead tree in a standing ghost forest in New Jersey. She’ll use the core to date the tree and start to assemble a timeline of when the marsh formed. (Irina Zhorov/The Pulse)

“We’ve had sea level rising for a long period of time, so why is it important now? But we’re seeing the fastest rate of sea level rise in 3,000 years right now,” she said. “Everything could shift backwards from the coast, except then you run into things like agriculture, or any kind of human development.”

Theoretically, coastal ecosystems can just retreat as the marsh pushes inland, but around the world, people have built up coasts with urban centers, levees, fields.

As if a reminder of that, right behind where Walker works stands a house, something else the swamp could soon swallow.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.