Can data help with suicide prevention?

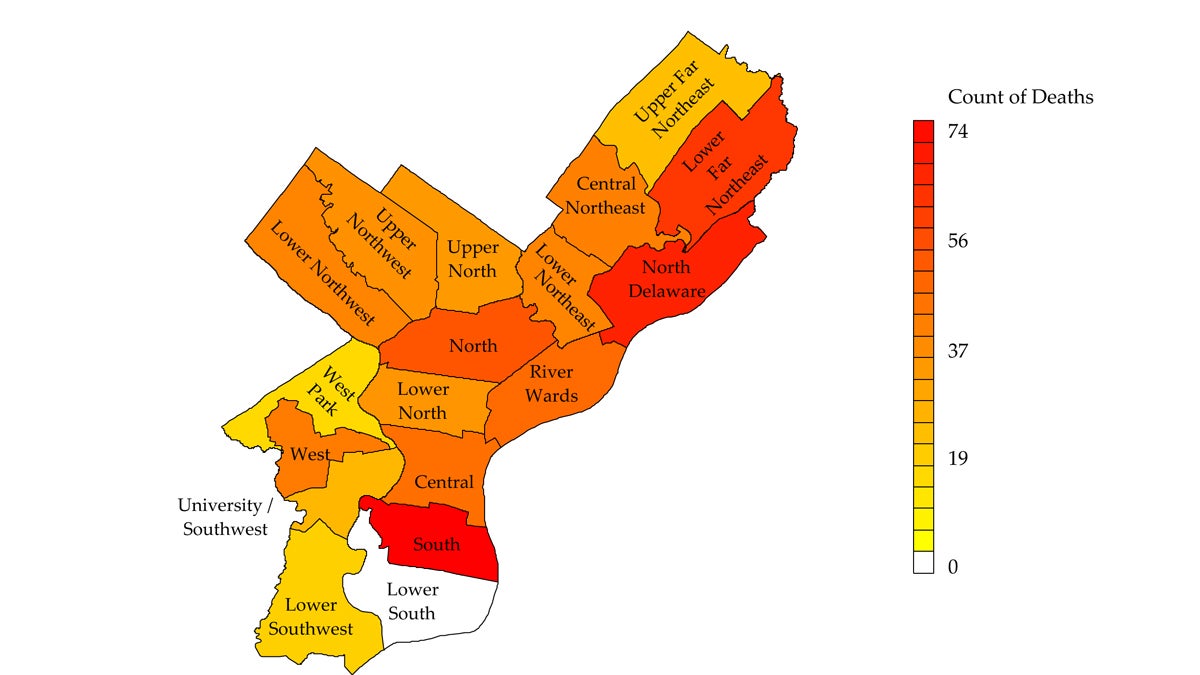

A map of suicide deaths by Philadelphia planning district between 2007 and 2011. (Image courtesy of Pennsylvania Department of Health)

Close to 40,000 Americans commit suicide every year, and that rate has been rising in the past decade, with an especially sharp increase among middle-aged people.

Could collecting and analyzing data help in preventing suicide?

To improve suicide prevention, you might start by gathering some seemingly straightforward information — such as where suicides occur geographically. But hard data on suicide is hard to come by.

“There is such a delay in getting the information nationally, as well as locally, that we’re looking now at info from 2011,” said Bob Gebbia, who heads the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “We have heard it mentioned from some of our friends in the federal government that they can get better information in HIV deaths in a country in Africa than they can get on suicide deaths in the U.S.”

Public health officials don’t routinely analyze or share in-depth information on suicide that goes beyond the most basic statistics — and the city of Philadelphia is no exception.

After weeks of asking the public health department for information on suicide in different parts of the city, officials finally compiled and shared a map that tracks suicides in Philadelphia between 2007 and 2011. There were 755 in total, with definite clusters in parts of South Philadelphia, North Philly, and the Northeast.

“It’s really interesting to see the patterns to say that, yes, there are places geographically where deaths happen more often than other places,” said Jonathan Singer, a professor of social work at Temple University who studies suicide prevention. Seeing this map leads to new questions about the areas where suicide is more prevalent, he said.

“Perhaps services are there, but nobody knows about them,” he said. “Is it a fact of there are no services, so transportation needs to happen?”

Factors such as bridges or train tracks could play a role as well.

“It would be fascinating to know that these are places where people die by suicide, but they don’t live there,” he said.

Cities such as Philadelphia could dig for more information when suicides happen, he suggested, and do something he calls a sociological autopsy. “What is it about the place, what is it about the place and the person, the person in the environment, that combination that contributed to this suicide death?”

Singer would like to gain access to more detailed information on suicides in the city. For example, ZIP codes of residence versus ZIP code of place of death, the method of suicide, and whether a person was involved in services prior to their death.

Philadelphia’s behavioral health commissioner Arthur Evans said that’s a question of resources, but generally he fully supports this kind of effort. “It would be a great idea, it would be fantastic, if we could routinely do that kind of thing when people are dying by suicide.”

The city is stepping up efforts to prevent suicides with public health measures such as “mental health first aid” trainings that help people recognize signs of psychological distress, Evans said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.