At Villanova, working to slim the power-hungry ‘cloud’

Listen

Al Ortega and Amy Fleischer

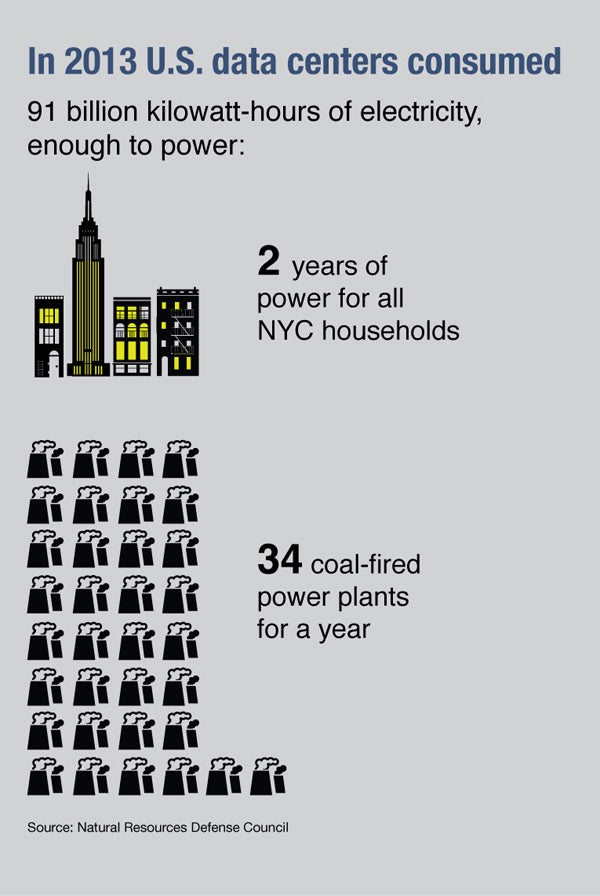

Data centers — both the big server farms that house “The Cloud” and the small systems storing company data — use over two percent of the nation’s power. According to a recent report on 2013, that’s enough electricity to run all of New York City’s households twice over.

A team of researchers from Villanova University is working to chip away at that figure, by capturing the heat that servers spit out and turning it into electricity.

And it all starts in a vacant, ’80s-era office building right on the Main Line, in Devon, Pa.

“Feels to me like when we come in here we’re working on top-secret research that nobody can know anything about,” said Al Ortega, a Villanova mechanical engineering professor and vice president for research.

It’s far from it, actually, but the empty building is eerily quiet — except, that is, for an old corporate data center, humming with a few racks of servers.

“Multiply that by about a thousand times and that’s what your typical data center sounds like nowadays,” Ortega said, over the din. “It’s like walking into a factory where they’re manufacturing jet engines.”

Computers get hot, and traditionally air has done the job of cooling them. You’ve probably felt a hot cell phone or some other overused gadget. That heat is not friendly to the chips inside. On the scale of a data center, cooling becomes a big deal.

Liquid cooling

What Ortega and his colleague Amy Fleischer are doing, is working to capture the heat generated by the servers and put it to work as something useful: fresh electricity that can power the data center itself.But the first step is liquid cooling.

“We’re just talking about hot water here,” explained Fleischer, also a professor of mechanical engineering at Villanova. “We’re heating up fluid as it comes across a chip and we’re using that hot system to generate electricity.”

Fleischer says using liquid cooling systems instead of air is a growing trend in high-powered data centers. What the Villanova system starts with is essentially a tiny boiler that turns that cooling-liquid into steam, which can then produce electricity.

“We’re going to capture that heat and then we’re going to use that heat to run a turbine and the turbine will create electricity that can then return back into the system,” Fleischer said.

It ultimately makes a more energy-efficient system meant to save data centers money.

“It won’t, of course, supply all of the electricity needs of the data center,” Fleischer said, “but anything that we can do to take a certain amount off the grid and off the national demand is wonderful. If we can create electricity out of the waste heat that’s coming off the servers anyway, this is just an economic benefit for everybody concerned.”

Fleischer is talking about turning maybe half of the wasted heat into something useful, be it for power or running cooling systems for buildings.

There are millions of data centers in the U.S., from your office’s server closet down the hall to the giant, middle-of-nowhere warehouses from the likes of Google, Facebook and Amazon — the kind that Ortega has trekked to before.

“I was expecting this ethereal experience,” he quipped. “In fact, I found a big-box-store-looking building out in a potato field. That’s the cloud. That big box consumes a huge amount of electrical power.”

New data centers from web giants are actually quite efficient, but all your Facebook photos and Gmail accounts still take lots of electricity to store.

Efficient or impractical?

Experts say the bigger problem may be the army of smaller, corporate data centers that tend to waste far more power.

That’s why the Villanova test facility represents such an energy-saving opportunity.

“[Data centers] all have the same problem: they run hot and they need to be cool,” Ortega said. Here’s a chance to make that waste heat, which is usually funneled outside, productive.

The work by Ortega and Fleischer at Villanova is still in the early stages. It’s funded by the National Science Foundation and supported by a few industry partners.

Dennis Symanski, an expert who studies data center energy efficiency at the Electric Power Research Institute, says the effort is one of just a few looking to put waste heat back to work.

“These are all good techniques,” he said. “We ought to take a look at using them where it’s appropriate and where you can actually get benefit from all the heat and power that’s put into the data centers.”

Another expert, however, says the Villanova approach is far from practical at this point.

Mark Bramfitt, an independent consultant who works with utilities on data center energy efficiency, says repurposing waste heat is very low priority for data center operators.

Cutting back energy usage on the front end is easier.

“It’s just far more effective from a cost savings standpoint to go after the power savings rather than trying to reclaim the waste stuff off the back end,” Bramfitt said.

A long-term approach

Back at Villanova, Al Ortega admits that the work there is solidly focused on the long term.

“Data center operators are getting more sophisticated, this whole industry is getting more energy conscious,” he said. “What we’re woking on here at Villanova and in our center are advanced concepts well beyond, well beyond what is currently being instituted in the industry.”

After all, the energy-consuming monster that is The Cloud is only getting bigger. And attempts to slim down its massive appetite for power will only multiply as our hunger for data keeps fueling its growth.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.