‘Exit counselors’ strain to pull Americans out of a web of false conspiracies

(Matt Williams for NPR)

Michelle Queen does not consider herself part of QAnon, but she does believe some of its most outlandish conspiracies – including that Satan-worshipping elites in a secret pedophile cabal are killing babies and drinking their blood.

“When you are evil, you’re evil,” says Queen, 46, from Texas. “It goes deep.”

Queen also believes the big lie that the Democrats stole the election from former President Donald Trump, and that the people who broke into the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 were actually undercover members of the left-wing Antifa, even though none of those who’ve been charged are affiliated with the far left movement.

“That’s who they said they arrested,” Queen says. “They didn’t tell you all the others. Y’know the news ain’t gonna give you the whole thing.”

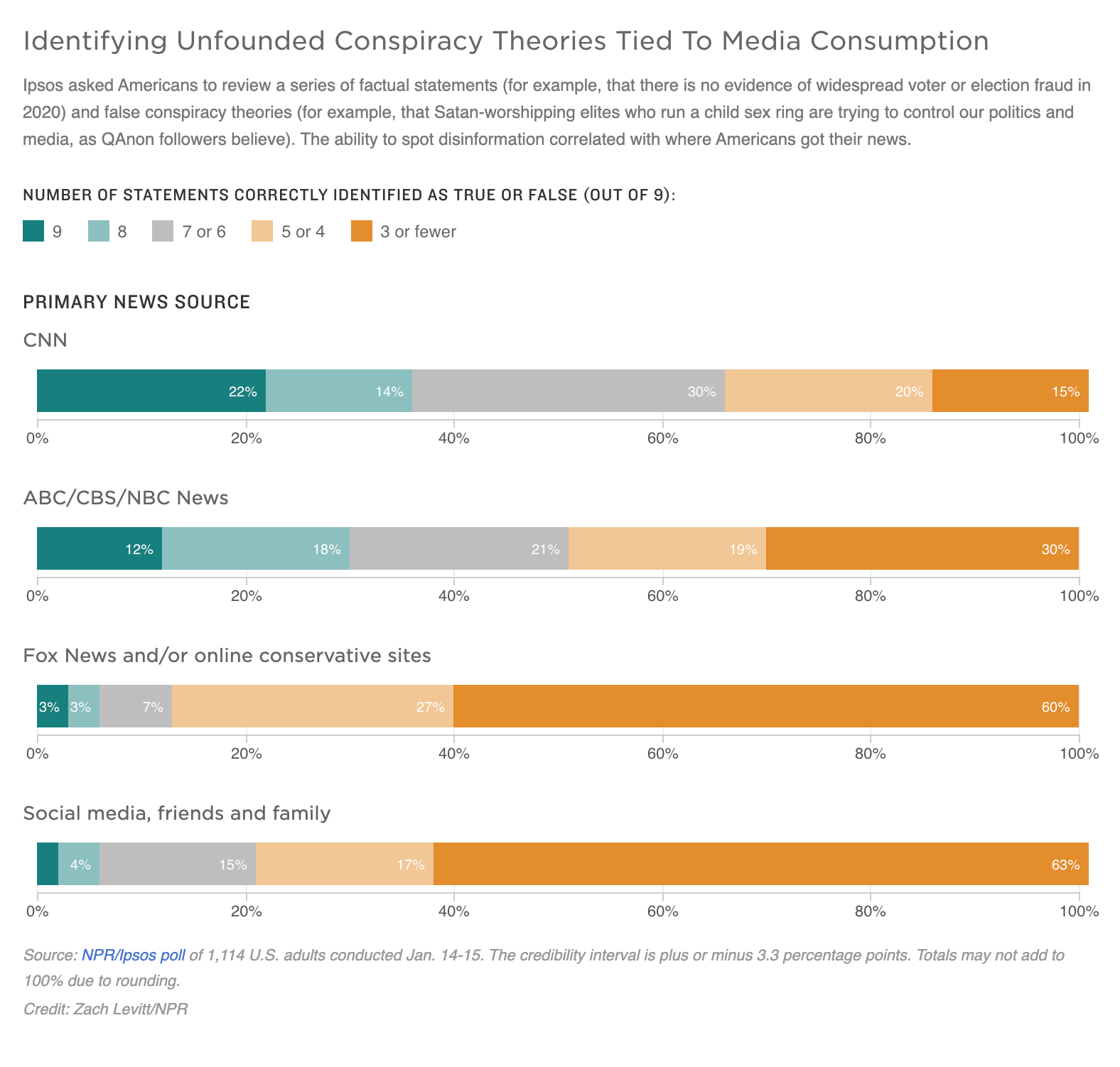

Queen is among an alarming number of Americans responding to a recent Ipsos poll, who mistook several false conspiracy theories for truth. While delusional conspiracy theories go way back, experts say right-wing disinformation, in particular, is now spinning out on an unprecedented scale.

Experts see this spread of disinformation as a public health emergency that’s threatening democracy, increasing the risk of further violence, and straining family relationships. It also taxing a bevy of “deprogrammers” who are trying to help. More commonly referred to as “exit counselors” or “de-radicalizers,” they help people caught up in cultic ideologies to reconnect with reality.

“I’ve probably got almost a hundred requests in my inbox,” says Diane Benscoter, who’s been helping people untangle from extremist ideologies since the 1980s, after she herself was extricated from the Unification Church, commonly known as the Moonies.

She recently founded a non-profit, Antidote.ngo to run Al-Anon style recovery and support groups for the unduly influenced and their loved ones. There’s no end to the need for those kinds of services, Benscoter says.

According to the Ipsos poll, more than 40% of Americans believed some of the most virulent and far-fetched disinformation — either the baseless claim that the election was rigged, that a Satan-worshiping child sex ring is trying to control our politics and media, or that Antifa activists were responsible for the Capitol riots.

‘It’s almost unfathomable’

Queen says she gets most her information from a trusted friend who “digs deeper” on the internet than she does. “She doesn’t even Google,” Queen says, “because she says Google doesn’t show you the right things.”

The poll found that those buying into fallacies are far more likely to get most of their news from social media, friends and family, or conservative news outlets. Or they were likely to have recently used social media platforms like Parler and Telegram, which experts say have become disinformation super-spreaders.

“It’s like a free-for-all,” says Joan Donovan, who heads up the study of online disinformation at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University’s Kennedy School. “It’s almost unfathomable.”

Indeed, anyone can be psychologically manipulated, Benscoter says. Cultic groups all tend to fill some psychological need or void, such as a desire for meaning, purpose, or community.

“It establishes this camaraderie and this feeling of righteousness and this cause for your life, and that feels very invigorating and almost addictive,” she says. “You feel like you are fighting the battle for goodness, and all of a sudden you are the hero.”

In other cases, the allure may be what Benscoter calls “easy answers to life’s hard questions.”

‘This is like a war on thought’

That’s what drew in 32-year-old Jay Gilley, a pizza delivery guy from Alabama who spent three years caught up in QAnon. It started when he questioned the Black Lives Matter movement online and got assailed. One click led to another, and he wound up deep into dark conspiracies and hate speech dressed up as dogma. But to Gilley, it felt like validation.

“Just having someone tell you you’re right, and don’t listen to people, it just leads you down that path so fast,” he recalls. “You want to be right so bad. You don’t want to be dragged back into that confusion.”

Eventually, thanks to a patient friend who stuck by him and indulged his questions, Gilley says he came to understand how he had “allowed himself” to go from a left-leaning supporter of former President Barack Obama to a guy who had fallen all the way down a far-right rabbit hole.

“Looking back at it now, it’s terrifying,” he says. “This is like a war on thought. Like are we just going to start fighting for thought control?”

For all the psychological operations, or PSYOPs, used to suck people into a cultic group, experts say, it takes just as much savvy and precision to help them out.

The approach has evolved since the days when some deprogrammers came under fire for crossing legal and ethical lines by holding cult members against their will. Today, experts say the engagement is voluntary, and more cooperative than confrontational.

Approaches to helping people exit cultic groups

The biggest mistake families make is trying to argue with a loved one, says Pat Ryan, another former cult-member who has been working in the field for decades, and now calls himself an “interventionist.”

When a family hires him to meet with a loved one, Ryan says his first step is to do a kind of intervention on the family. He implores them to change their tone to be less adversarial, disdainful or mocking. That’s counterproductive, typically causing a person to just dig their heels in, Ryan says. Also, if he gets the family to back off a bit, he scores instant points with the loved one he’s ultimately trying to reach.

“It’s strategic, absolutely,” Ryan says. “Then I have credibility. And so then, we have a path to go on.”

Another approach to helping people exit cultic groups is a kind of mirror image of the tactics used to lure them in.

QAnon, for example, is known for dropping “bread crumbs,” or little clues that followers piece together to draw their own conclusions.

“That feeling of ‘I did my own research, and I didn’t just believe what I read in the newspapers’ makes believers more emotionally invested,” says Arieh Kovler, who researches online extremism and disinformation. “They believe it much stronger.”

Experts say that works in reverse, too, to help people reconnect to reality.

Steven Hassan is a former Moonie who has also made a career of helping people relearn to “think for themselves.” His approach is to “ask gentle questions” and then allow people “to connect the dots themselves.”

For example, Hassan will ask a person to recount how they first started buying into the ideology or group, hoping they, themselves, may start to recognize ways in which they were manipulated or led astray.

Hassan, author of The Cult of Trump, says shame and humiliation can also be enormous hurdles for someone interested in quitting a cultic group, and returning to their old lives. It’s why he recently helped launch a hashtag campaign, #IGotOut. He hopes destigmatizing those who have fallen prey to disinformation, and might make it easier for them to get out with their dignity intact.

Much easier said than done

Of course, it’s all much easier said than done. Michelle Queen, for one, is adamant that no one can change her mind. But as she put it, the Bible teaches that “discernment is a gift,” and since she’s confident that she’s got it, she agreed to sit down with Benscoter, just to hear her out.

“Hi, Michelle,” Benscoter begins tentatively. Hoping to set a tone of humanity and compassion, she starts by asking Queen how she’s faring in the aftermath of last month’s snow storm in Texas, and expresses gratitude that she’s warm and well.

Then, Benscoter walks a fine line. She’s upfront that her aim is to get Queen to consider the possibility that she’s caught in a web of disinformation, while at the same time, she insists she’s not trying to change her by turning her into a Democrat, for example.

“That’s not what I’m about,” Benscoter tells Queen, “even a little.”

Then, Benscoter wades in, carefully making the case that anyone can be duped, making sure never to take aim at Queen. Instead, she offers up herself as Exhibit A, explaining how she – when she was a Moonie – thought she was following the Messiah.

“I know that sounds outrageous,” she sighs, “but I was wasn’t stupid, and I just … one thing led to another, and it kind of fed into some fears that I had, and it just kind of just pulled me in. And next thing I knew, I had cut off all contact with my family.”

Queen listens quietly as Benscoter explains how extremist groups need to control what people think in order to convince them to dedicate themselves to a cause, and so these groups paint everything else as a lie or evil. And she tells Queen how those indoctrination tactics worked on her.

“I started believing that all information, from regular news sources, or different faiths or churches was wrong,” Benscoter says. “They became like the enemy.”

A few minutes in, Queen starts to push back, insisting she’s not the impulsive or emotional type who would do that.

“I pray on everything,” she says. “I’m not in a cult. Nuh-uh.”

It was the first of many times during their conversation that Benscoter would back off and pivot, in search of even the tiniest patch of common ground.

“Well,” she says at one point, “one thing that I think is so sad right now is that the country is so divided, people are almost like spitting at each other. And that’s not what our country should be.”

Finding common ground

“Right! That’s right!” Queen responds.

Before long, they’ve found even more they can agree on: that the violence at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 was wrong. “I’m not a fan of some of the Democrats,” says Queen. “But it doesn’t mean they need to be tortured or killed.”

They also both abhor the idea of hurting children – even though they disagree on how much of the fantastical, horrific stories are actually happening. Benscoter senses an opportunity to take one more shot at dispelling the disinformation.

“Some of the things that are being spread about babies being eaten and things, I don’t think those things are true, personally,” Benscoter says.

“Um, I do!” Queen interjects.

“I know you do,” Benscoter says. “And we need to get to the bottom of that.”

“Now, how would we do that?” Queen asks. “How do we prove they’re not doing that? I don’t put anything past people.”

Benscoter talks about the many reputable non-profits fighting human trafficking, and suggests Queen might like to get involved.

She also cautions that when people are suffering — like they are during the pandemic — it’s easier to get them riled up,” and how big-hearted, caring people can be especially “susceptible to buying into things.”

And Benscoter warns Queen about believing everything from a trusted friend; they may have the best intentions, but anyone can be deceived, she says. Instead, she suggests neutral sources, like academic research that Queen can read herself.

But Benscoter is careful not to come on too strong, and not to tackle too much, at least for this initial conversation.

Indeed, the idea is never to “snap the person out of it, or do an ‘a-ha’ moment where it’s a light bulb,” says Steven Hassan, “but rather to do incremental ‘A-ha’s'” so the person may slowly realize what doesn’t add up.

When Benscoter’s conversation with Queen veers off toward an area of disagreement one more time, Benscoter makes one last pivot to try to end on a more congenial note. She expresses sympathy for how Queen’s business has been hurt during the pandemic.

“I know it’s been really tough,” Benscoter offers. “I think now is the time to start building bridges, you know.”

“That’s right,” agrees Queen. “And sturdy bridges! Nothing that’s going to fall apart!”

“Yes, I’m with you,” Benscoter answers, as the two have a good laugh.

A tedious and time-intensive process

By the end of the conversation, they agree to keep talking, just what Benscoter hoped would happen.

“It may seem like you’re being tricky or crafty, but really what you’re doing is respecting the fact that this is not going to be an easy process for [people] to get out with their dignity.”

But it’s a tedious and time-intensive process, and one that Benscoter concedes, cannot keep up with disinformation spreading virally online.

The only viable strategy is prevention, she says, which is why she’s helping to develop a public awareness campaign to help keep people from falling down the rabbit hole in the first place.

“I think it’s really important to try to help people inoculate, to try to create herd immunity to psychological manipulation,” Benscoter says, “and to hit that tipping point in society where more people understand how these tactics work, and those who try to use them will be less successful because those using them are easily spotted now.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))