Episode 1: You don’t have to drop a bomb

(6abc)

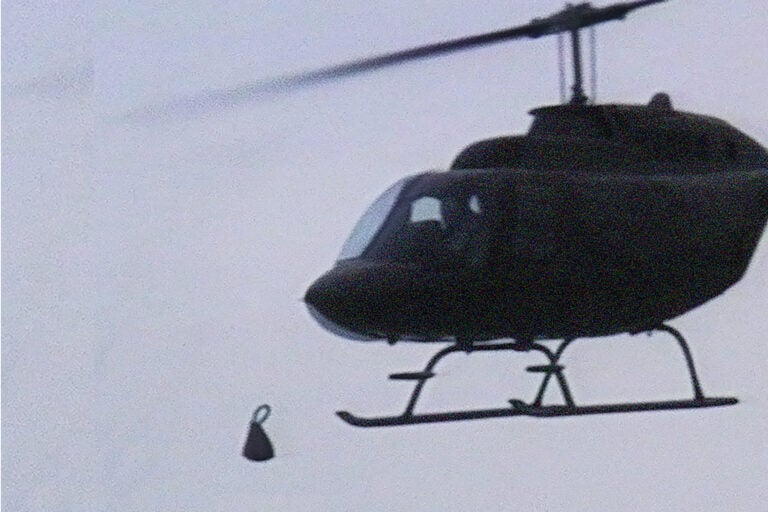

Forty years ago, the City of Philadelphia used a helicopter to drop a satchel bomb the size of a backpack on a group of residents. For the first time, a helicopter pilot who flew the route ahead of the bombing shares his story. He advised the city that “the bunker’s no threat.” And yet, the city dropped the deadly bomb on May 13, 1985.

-

Episode transcript

MOVE @ 40 Podcast

WHYY News

Episode 1 Transcript[SARAH GLOVER]

Hello, I’m Sarah Glover WHYY’s vice president of news and civic dialogue. This twopart series reported by Tom MacDonald uncovers an untold story about the horrific MOVE bombing that rocked the city of brotherly love 40 years ago.

This is the story that people need to hear, the stunning firsthand account of a helicopter pilot who flew the route and advised the city that “You don’t have to drop a bomb.” end quote. Content warning. This episode contains descriptions of violence, death, trauma and a bomb.

[TOM MACDONALD]

It is a moment frozen in Philadelphia history. The bombing of a rowhouse in West Philadelphia that resulted in death and devastation. Eleven people died including children and 61 homes were decimated from the resulting fire.

[MAN’S VOICE]

I don’t know Harvey could what kind of activity is…”

[TOM MACDONALD]

I’m WHYY news reporter Tom McDonald. This is Move at 40 episode 1. You don’t have to drop the bomb.

I covered the 1985 MOVE bombing and now 40 years later, I’m taking a look back at others who were there in the days leading up to the city’s decision to drop a bomb on its own residents. The order went against the recommendation of the helicopter pilot who did the initial surveillance.

[MARK CICCONE]

I said the bunker’s no threat. There’s nobody in it. It’s just a bunch of rows of sandbags with a little gas can. There’s nobody in it. So, you don’t have to drop a bomb on that.

That’s for sure. There’s nobody in it. It’s not a threat. Um, but they felt otherwise, so they wanted that bunker blown out.

[TOM MACDONALD]

This exclusive story from the helicopter pilot is riveting, and now for the first time he’s sharing his reflections on that deadly day. More of that coming up.

On May 13th, 1985, police were given two orders. Arrest four members of MOVE, a group that emerged in the 70s as a back to nature movement, but transformed into a black liberation group that later sparked controversy and tension with law enforcement. The second order was to remove children living at the MOVE residence on Osage Avenue. Police leaders worried about a bunker built atop the home.

They were concerned it gave MOVE a tactical advantage and the ability to fire on officers at will. At one point, officials tried to figure out how to use a crane to remove the rooftop bunker. Police commissioner at the time, Greg Sambor, testified during the MOVE commission the action was discussed for about two hours.

[GREG SAMBOR]

Well, we were told finally to the best of my recollection is is that it could not be done in any way other than a frontal assault and by a mechanical operation, not by swinging a ball or anything because of the clearance was prohibitive, but that by some mechanical operation is to go up and push it off by mechanical pressure.

Uh and uh that there was no way in which the safety of the operator could be guaranteed.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Sambor said they determined there was only one entry point to the house that they could use.

[GREG SAMBOR]

A frontal assault would have been prohibitive. A rear assault was prohibitive. Coming in through the lateral entry of the buildings had already proved to be ineffective.

The only That left us only one recourse and that was in to if we were to get any control of the situation in any reasonable amount of time, it would have been to go through the roof.

[TOM MACDONALD]

In order to gain entry through the roof, the bunker still had to be removed. Police decide to scout the bunker via air by using a traffic service helicopter that gave reports to city TV and radio stations.

Mark Ciccone flew the helicopter he operated for a traffic service known at the time as the SnoCo traffic update. He knew what was going on because of a close relationship with police.

[MARK CICCONE]

Apparently, it was well planned, you know, in in police circles and the city circles. Um, we were advised advised that what was going on because I had a highway trooper on board at all times because in those days Philadelphia didn’t have their own helicopters.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Chikoni is a former Vietnam pilot who had combat experience, another trait that was called into play on the day of the MOVE confrontation. He was asked to fly over 6221 Osage Avenue in a reconnaissance mission. He did the first pass at a speed of almost 150 miles an hour.

[MARK CICCONE]

First thing I did was a high speed run. So, I had, you know, that Jet Ranger going as fast as it probably could possibly go, maybe 126-27 knots. And just feed off the rooftops because I didn’t want to give them any chance. This is the same tactic we use low level um attacks. The same. We didn’t want to give them any chance to oh here comes a helicopter. No chance to fire at me, which they did anyway, but they didn’t have any chance of hitting me. So that was a low level pass and I had the helicopter turned up on its side and I was looking right down that that bunker as we we flew over.

[TOM MACDONALD]

The helicopter had access to police frequencies and Chaconne was warned by police observing across the street from the headquarters The MOVE members are trying to shoot the chopper down.

[MARK CICCONE]

Harry was a SWAT guy. He was in the building across the street, good friend of mine. And he radio’d that they’re shooting at you as I did the recon.

Um so they got guns that sticking right out the wind and they’re trying to hit that like or they missed fortunately.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Ciccone knew about the plan to use an entry device or satchel bomb as it was referred to by those who built it. He was experienced with them while in combat. After looking at the bunker, he told police using was unnecessary.

[MARK CICCONE]

I told him whatever you do don’t bomb it. It you don’t need to. My my report back to them, my considered opinion with a lot of experience doing exactly the same thing was totally unnecessary. It’s a little tiny bunker, maybe three rows of sandbags high with a gas can sit next to it. No, no activity. I don’t even see any hatch open on the roof for access. Um so don’t do it. Uh, but they felt otherwise, so they wanted that bunker blown out.

[TOM MACDONALD]

But why was a civilian helicopter being used for the surveillance flight? Ciccone said the weather kept the state police from flying down to the city.

[MARK CICCONE]

It was a drizzly day, gray day, light rain, and uh the state police who were tasked to drop the bomb couldn’t get down from Redding, which was their home base.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Even though he was against the move, the decision was made to move forward with the bomb. And Ciccone said he flew up to the police academy in Northeast Philadelphia to pick it up. He describes the device.

[MARK CICCONE]

The satchel charge, this what we called it in Vietnam. It was like the civilian would think it was a bag with a handle on it. And it was all in, you know, it doesn’t look like you’re like a bomb that the typical person would think comes out of an aircraft. It was a satchel charge. Um, used extensively by the Viet Cong in the in the Vietnam War.

We didn’t use the much at all. We had more sophisticated stuff. But that’s what it was. It was a bomb in a bag. And it was only about say 25 pounds, 30 pounds and easily handled by one person.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Police loaded both the bomb and the officer tasked with dropping it into the traffic helicopter. But just moments before they were to drop the bomb, they received a message over the radio from the state police.

[MARK CICCONE]

Just moments before we were to fly over and drop it to the We got a message from the state police that they were on their way down, they made it. So, I flew over to a little schoolyard in West Philly. Landed in the schoolyard and the state police landed next to me. We transferred lieutenant and the bomb over to the state police. And then we continue to fly high cover for him. Just keeping eyes on, you know, as I said, they were shooting at everybody.

[TOM MACDONALD]

The bomb was dropped from the state police helicopter at 5:27 p.m. It contained the combination of C4 military explosives and TOVEX, a water gel explosive, a type of blasting agent that’s largely replaced dynamite in applications. It’s known for being safer to manufacture, transport, and store, and also has a lower toxicity compared to dynamite. Ciccone was high above the rooftop when the bomb hit.

[MARK CICCONE]

It certainly worked. It blew the bunker completely apart. So, that worked. Um, it wasn’t like they overpowered the the bomb didn’t destroy the roof of the home or anything like that. I don’t think it was designed to do that. And but subsequently it caught that can of that gallon can of gasoline on fire and that that caught the house on fire.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Pete Kane was a photo journalist for Channel 10. He was able to hide in the house across the street from the MOVE compound after the neighborhood was evacuated on Sunday night. His description of the time leading up to the bombing, including police and major fire fight with MOVE members and the use of several means to attempt to extricate the men, women, and children from the encampment.

[PETE KANE]

Throughout the day, they estimated 10,000 rounds of bullets were fired from 10:06 that morning until I left the house 8:30 Monday night. So, throughout the day, I went through uh tear gas being fired down on on Osage Avenue. Um, I was smelling the tear gas, the bullets whizzing by.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Before the bomb was dropped, fire department deluge guns were trained on the bunker trying to use their high pressure streams to eliminate it. Kane watched as the fruitless effort continued.

[PETE KANE]

What I was looking at was is a fortress on the top of that house. I mean the the lumber they used was heavy lumber because the fire department hit that thing with everything they could with that deluge gun that was thousands of pounds of pressure. Only thing that came off of that bunker was the wrap that was around it like a tarp that was on the outside of it that would never bolt pieces of wood came off. And but as far as that bunker goes, it it stood there. It withstood hours of hours of being hit with water. Um the only thing you can see is wood debris coming down into the street. The tarp that was on the outside and coming down on the street, but that bunker never moved.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Kane says he remembers the feeling when the bomb struck the house and he still believes people were alive inside.

[PETE KANE]

When the bomb was dropped and when I went upstairs out the window, I saw the flames. I was saying to myself, please come out the house. I knew they were in there cuz throughout the night I heard them. I heard Ramona. I heard a male person on the bullhorn. So, I knew that people may have still been in that house cuz I never saw them come out. I never heard anything that from the station that hey they you know they came out they’re out. So, at my mind I knew people were still in 6221 Osage Avenue.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Kane eventually evacuated his perch at a point when he feared for his own life. Once the bomb was dropped and the gasoline caught fire, the controversial decision was made to let the fire burn for several reasons. Police wanted to clear the roof of the bunker and firefighters didn’t want to fight the fire because of the fear of being shot by MOVE members. During the MOVE commission hearings, Charles King, an expert in the cause and spread of fires, did a play-by-play of pictures and video from the fire that started after the bomb was dropped. He said the deluge guns were turned on but had very little effect.

[CHARLES KING]

This is the uh deluge gun which is put in operation on 62nd and 0 Sage. Uh it’s it’s not having an effect of putting the fire out. What it’s trying to do is to contain it. Uh the only way you can really stop a fire of this magnitude is to bring forces down Osage Avenue. There again, this is on man on man because of the threat of gunfire or gunfire.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Fire department crews finally were able to fight the fire conventionally at about 9:30, four hours after it started. At that point, King said under questioning from commission member Charles Bowser, there was no stopping the flames as they went from home to home. It was an effort to designed to keep the spread to a minimum.

[CHARLES KING]

At this time when it was permitted to fight the fire, they had 50 homes involved in fire. [CHARLES BOWSER]

Uh, Mr. King, let me understand. Are you saying that it was about 9:30 when they were permitted to fight the fire in a normal fashion?

[CHARLES KING]

That’s correct, sir.

[CHARLES BOWSER]

Uh, if I could just stop the film.

[CHARLES KING]

Yes.

[CHARLES BOWSER]

For one moment and ask you one other question. You alluded to some civil unrest situations in New York

[CHARLES KING]

Yes, sir.

[CHARLES BOWSER]

That made firefighting in a normal fashion risky and impractical.

[CHARLES KING]

Yes, sir.

[CHARLES BOWSER]

Uh, and I assume you were aware of other civil unrest situations that sort of changed the balance in terms of whether it was was a police scene or a fire scene. [CHARLES KING]

That’s correct.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Fire Commissioner William Richmond said, “Fighting the fire also cause problems.

[WILLIAM RICHMOND]

Porches are a horrendous problem for firefighters. The fire will get under there and like a tunnel effect and just whip right down the porches. That happened through those partitions that Sergeant Connor explained to that he blew out on one occasion. The second critical problem was the backs of both of these houses on the north side of Osage and the south side of Pine had bay extensions, which are frame extensions. And when the heat radiated across the alleyway, it didn’t take long to get those going.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Photojournalist Pete Kane realized that himself when he made the decision to flee the home where he’d been hiding.

[PETE KANE]

I did not leave the house I was in till 8:30, which was 3 hours after the fire got out of control when my station told me to get out of there because I’m feeling a heat. I’m not not even not even a quarter block away from where the MOVE house was. And by that time, all the homes on the north side of Osage Avenue was fully engulfed in flame.

[TOM MACDONALD]

Kane said he’ll never forget that day and glad he was a photo journalist, not a police officer as he originally wanted to be as a younger man.

[PETE KANE]

May 13 is the nightmare. It’s always going to be a nightmare for me and the people I work with, I’m sure.

[TOM MACDONALD]

MOVE at 40 is a production of WHYY News. I’m Tom MacDonald, the reporter and fill-in host at WHYY. Our executive producer is Sarah Glover, WHYY’s vice president of news and civic dialogue. Our editor is Mark Eichmann, WHYY News senior managing editor. Our engineer is Charlie Kaier.

Some of the audio provided by the Temple University Archives, which houses the WHYY broadcast of the MOVE commission. Funding for this podcast has been provided by WHYY. Please rate and review this content wherever you get your podcast and share on social media. Visit WHYY dot org for more news content on the MOVE bombing. Thank you for listening and engaging.

collapse

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by MOVE Bombing @40

![MOVE Podcast Tile_FINAL[85]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MOVE-Podcast-Tile_FINAL85-300x300.jpg)