Why is Pennsylvania’s water expensive?

Flickr Creative Commons)" title="water_drips_1200" width="1" height="1"/>

Flickr Creative Commons)" title="water_drips_1200" width="1" height="1"/>

Water drips from a faucet. (File image by nekidtroll via Flickr Creative Commons)

A recent ranking of the nation’s 500 largest water systems found the highest rates charged by private companies in Pennsylvania.

Aging infrastructure and an investor-friendly regulatory climate contribute to costs, experts say.

This caught our attention because multiple commonwealth cities are considering privatizing water treatment and delivery, or have done it recently.

Why do cities consider privatizing? To finance system improvement, generate cash for a relatively unrelated obligation, or both.

Findings

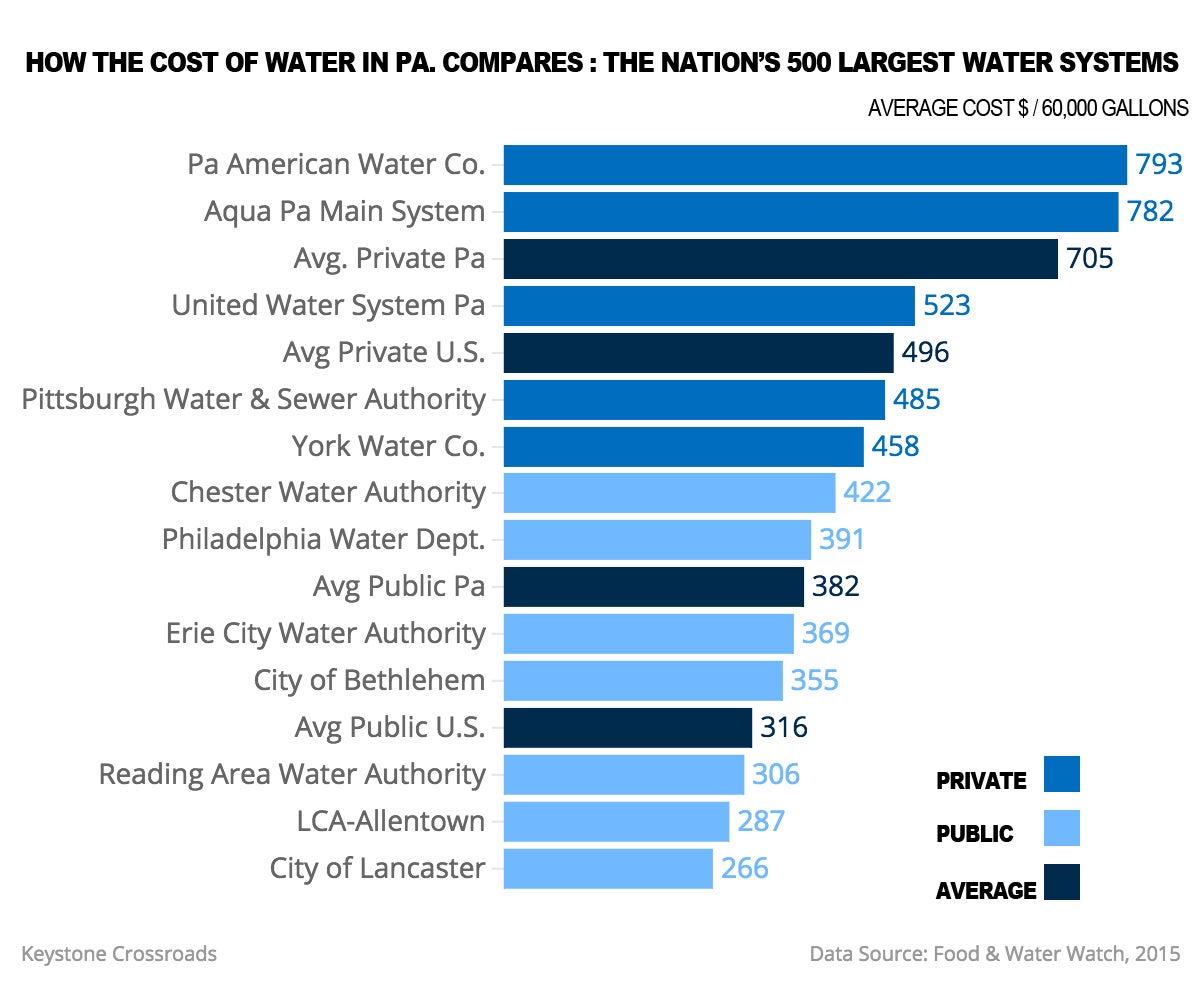

The chart above gives a detailed look at rates charged by 15 of Pennsylvania largest water systems serving about half of the 10 million or so residents (between 2.5 and 3.5 million state residents use well water, based on a survey and Penn State estimates, respectively).

Food & Water Watch compiled the list of rates. The DC-based nonprofit advocates for, among other things, public ownership of water utilities.

Private water costs an average 55 percent more than water from systems run by municipalities and other public entities, the report notes.

Private operators pay taxes. They also have shareholders, whereas there’s not the same profit motive for a municipal authority or municipality. In that respect, it’s not surprising that private companies would charge higher rates.

“We’re public, they’re private. They make more, we know that,” says Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Association Deputy Director John Brosious.

But in Pennsylvania, it is more pronounced:

Of the 19 Pennsylvania water systems included in the survey, the average private rate in Pennsylvania is 84 percent more than the public rate average. The national markup is 55 percent, according to an analysis of the data.

The average cost for water provided by private companies is 43 percent higher in Pennsylvania than nationally; on the public side, it’s 21 percent higher, an analysis shows.

Good deals, not too slowly

Systems of both types face more of an expense in Pennsylvania because the state’s drinking water infrastructure is in relatively bad shape, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Often, companies that acquire municipal systems find infrastructure issues long deferred, which drives up rates with the switch to private ownership, says Pennsylvania American Water Company spokesman Terry Maenza.

The still-more dramatic premium on private water in the commonwealth also is attributable to a regulatory environment that the investment community considers a “gold standard,” according to Janney Capital Markets.

The Janney reports, which scored states on factors conducive to business, reference the Public Utility Commission, specifically.

(About 85 water systems fall under PUC jurisdiction. They include both private companies and municipal utilities with customers living outside the municipality. The PUC doesn’t regulate water systems operated by municipal authorities or by municipalities serving only residents, which account for about 2,500 other systems, most of them small)

Janney’s experts looked at what kinds of costs the PUC, and counterparts elsewhere, allow water companies to pass on their customers.

One is the rate of return on equity, or investment. Pennsylvania’s law says companies can increase rates to provide for a “reasonable” rate of return, and the PUC has discretion over what that means, exactly. It varies, so Janney averaged recently-approved figures to compare states. Pennsylvania’s number was 10.3%, which ranked fourth in 2013. The highest was 12 percent, in Washington, followed by Texas (11.4%) and then Maryland and Hawaii (both 10.4%), according to the report.

Another factor is something called a distribution system improvement charge, or DSIC (insiders call it a “disc”). That lets water companies recoup costs from customers for infrastructure improvements without applying for a full-blown rate change. This speeds up and simplifies the process for utilities and regulators, since the scope of the request is more specific. Pennsylvania was the first state with this surcharge, up to 7.5 percent of revenue annually. The majority of states in the Janney report haven’t implemented anything similar. But some states have, a few with more liberal guidelines (Maine and Ohio allow 10 percent per year, for example).

Janney also looked at the relative speed of state bureaucracies. They consider Pennsylvania middle of the road.

The report doesn’t mention public-private partnerships. But in Pennsylvania, companies can charge customers more than for infrastructure improvements if they paid for the projects by borrowing money from PennVest, the state’s infrastructure investment bank. That’s a separate surcharge from the DSIC, which helps to ensure the state gets paid back this low-interest loan, says PUC spokesman Nils Hagen-Frederiksen.

The point of these incentives is to entice private companies to take over small water systems that aren’t viable, according to Pennsylvania statute.

In addition to explaining rates, these rules shed light on why privatization is trending in Pennsylvania.

What it means

Local governments and other municipal agencies face drinking necessary water infrastructure repairs and improvements totaling $13.9 billion over the next 20 years in Pennsylvania alone, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.

They typically can borrow money at lower rates than private companies. But if the municipality’s distressed — like so many are in Pennsylvania — borrowing might be impossible or extremely expensive. In that scenario, private companies provide a cheaper option for financing system improvements.

And a sale means cash up front. Cities can use that to shore up a distressed retirement fund, as Scranton is contemplating. The city of York recently advertised for bids to do the same, says Brosious.

Allentown improved its pension health using cash from its water system. But that’s a long-term lease to the Lehigh County Authority. The deal kept the system public, which means more transparency and control. Nonetheless, rates increased.

The distressed city of Coatesville got $38 million when the city’s authority sold its water system in the 1990s to Pennsylvania American Water, the state’s subsidiary of the nation’s largest water company. City fathers spent good portion of proceeds unwisely, as this Al Jazeera story explains.

Listen to Emily Previti on Smart Talk as she discusses the Food & Water Watch report that found Pennsylvanians who get their water from private-owned water utilities pay some of the highest rates in the country.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.