Applying proven flood controls along with green infrastructure, Philly stays above water

Listen

When Philadelphia gets too much rain for its storm sewers to handle, millions of tons of sewage drain into surrounding rivers.

Many of the city’s sewers are from the 19th century. And with climate change projecting a soggier future for Philadelphia, the city’s water department is working hard to be able to accommodate all that extra moisture.

Instead of building ever larger storm sewers and treatment plants, the department has been investing in “green infrastructure” so more rain is diverted or absorbed into the soil. That all adds up to meeting an ambitious goal months ahead of schedule.

Chris Crockett’s team at the Philadelphia Water Department has already greened 750 acres of public property — well before the expected completion date in June. But the deputy commissioner isn’t taking it easy.

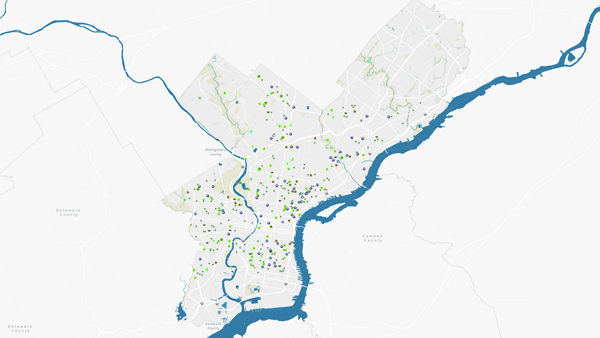

City of Philadelphia Green Water Projects Map (Electronic image via phila.gov)

City of Philadelphia Green Water Projects Map (Electronic image via phila.gov)

“From 2011 to now, we’ve been trying to take it from trying a couple projects here and there to actually building hundreds of projects and then figuring out how to operate, maintain and monitor them,” Crockett said. “In the next five years, we’re going to have to double the rate that we’re producing these things.”

The federal Environmental Protection Agency is encouraged by the short-term improvements of this approach.

“I think what distinguishes Philadelphia from a lot of cities is the scale of the commitment to green infrastructure in tandem with traditional controls,” said John Capacasa, the EPA’s director of water protection for the mid-Atlantic region. “We’re going to continue to monitor them to make sure that they’re accountable for results in the long term, not just in terms of greened acres.”

The goals are cleaner rivers, managing stormwater and improved quality of life. EPA officials call it the “triple bottom line” because these projects are cost effective, spur economic development and improve neighborhoods.

‘Big Green’ partnership

A seven-acre stretch of formerly abandoned lots in Kensington, now called “The Big Green Block,” illustrates the triple bottom line.

The Philadelphia School District, streets department, parks and recreation, and the Horticultural Society all invested here over 10 years. The water department provided rain gardens, street trees, and underground water-retention systems. And the New Kensington Community Development Corporation kicked in some money too.

The community group’s deputy director Shanta Schachter said that while everyone loves a new playground, it took a while for residents to adjust to the rain gardens.

“There were some kids in the neighborhood who used it as their dirt bike jumping ground. There were people who were afraid that the grasses and greening were going to bring bugs,” she said.

The solution? A sign, full-grown shrubs and a small fence.

The water department’s Crockett doesn’t worry too much about landscaping mistakes. “The good news is they’re only plants. It’s not like we’re tearing out pipes and putting a lot of concrete in,” he said.

Creating a local market

The goal of improving a neighborhood, as well as cooperation among city agencies are vital to the program’s future success, Crockett said. But so is finding ways to encourage the private sector to help.

The program employs local firms that design and maintain the green stormwater infrastructure. It has partnered with AmeriCorps to train young people — many of them ex-offenders — for the GSI jobs.

And business is booming. A new report from the Sustainable Business Network said Philly’s new GSI market grew 13 percent from 2013 to 2014, including everyone from engineers to landscapers. “We are seeing rapid growth, and we are seeing growth that we feel is different and better than what we see in other industries,” said the network’s executive director Jamie Gauthier.

Crockett said the water department wrote regulations to encourage this sector:

“We’ve created a market. We create regulations that say if you’re a developer, you have to manage [part of the] runoff from any hard surface,” he said. “And, on the other end, we create a billing process where you get charged for that pavement. And those create the bookends for private industry to come up with all kinds of ingenious ways to do that.”

New infrastructure, renewed neighborhoods

Back at the Big Green Block in Kensington, $25 million in private dollars has been invested within a two-block radius. The various partners involved credit the projects, saying it’s not just because the neighborhood is on the upswing.

Schachter of the New Kensington Community Development Corporation is now working to maintain affordability — in a neighborhood that used to worry most about blight.

“You make something look a little nice, you make it a little safer and then the private market and development community doubled down on that effort to provide additional eyes on the street,” she said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.