Unregulated and unstoppable, recovery houses proliferating in Lower Bucks

Listen

Debbie Fleming

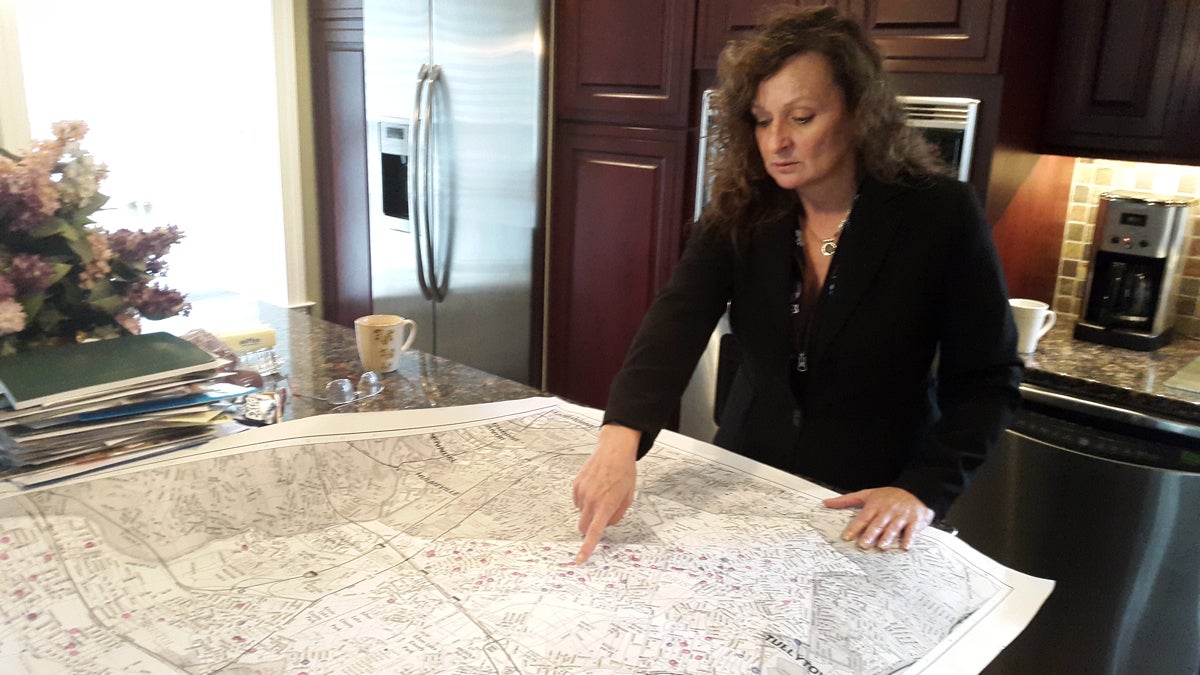

Councilwoman Amber Longhitano spreads a map of Bristol Township over her kitchen counter. It’s marked like a war plan, with pink and blue dots, representing the 95 “official” recovery houses located in the 17-square-mile township.

Some neighborhoods have one. Others have a half dozen. Taken together, they represent a snapshot of one unusually concentrated pocket of addiction services in suburban Philadelphia and the challenges that concentration present to residents and those in recovery alike.

Though they are an important part of the treatment process, recovery houses are completely unregulated by the state of Pennsylvania and at the federal level. That leaves local officials including Longhitano to grapple with their unchecked growth and try to shut down unsafe houses.

Bristol Township Councilwoman Amber Longhitano points to the locations of recovery homes in her township. (Laura Benshoff/WHYY)

Bristol Township Councilwoman Amber Longhitano points to the locations of recovery homes in her township. (Laura Benshoff/WHYY)

Many people who leave residential treatment or detox centers for drug or alcohol addiction aren’t immediately able to live on their own. Recovery houses, also called “sober living” houses step in to fill that void.

Why Bristol Township?

Bristol — with its affordable split-level houses, proximity to transportation and treatment centers, and critical mass of existing recovery houses — has become their hub in Lower Bucks.

“When I started this four years ago, we had 42 recovery houses in Bristol Township,” said Longhitano. Ninety-five is now the official count, though that number doesn’t include the couple dozen recovery houses believed to be flying under the radar.

That’s not to say residents in Bristol aren’t upset.

“They’re kind of surrounding us here,” said Debbie Fleming, 35-year resident of the Goldenridge section of Levittown in the township. Fleming and a group of her neighbors have been going to town council meetings, lobbying for the township to pass a zoning ordinance that would restrict new houses, like the one passed in neighboring Falls Township.

Earlier this year, Bristol Township Council did pass a curative amendment, effectively lifting the hood on its zoning for group houses and initiating a stay on any new houses.

All are recovery houses are not created equal

With 47 houses spread among 20 member organizations, the Bucks County Recovery House Association is a voluntary, self-policing group that nonetheless represents the extent of accountability for the township’s recovery houses.

Like other self-governed recovery associations across the country, the Bucks group models its houses on the nuclear family unit.

“The rules, the signing in and signing out, the random urine testing are things to keep you accountable like mom and dad did when you were younger,” said Don Colamesta, association president and operator of Acceptance House.

This model of recovery house differs from a treatment center in a few crucial ways: no treatment services take place in the house and staff aren’t professional counselors. House managers tend to be residents who are more advanced in their recovery who receive a break in rent for offering mentorship and enforcing the rules.

Chase Bressler, an affable 32-year-old living at one of the Acceptance Houses, bounced around a dozen recovery houses on his path to sobriety. He credits them with helping him grow up.

“At first, I didn’t know how to cook, do my wash, I didn’t know how to hold a job,” he said. “The first recovery house kind of taught me how to do that kind of stuff.”

Aside from creating accountability and structure, these houses function as a business. Members pay between $160 and $200 a week and are expected to get a job or pay with disability or other private income. State funding for recovery houses is limited to a few referral circumstances, and it’s usually only enough to cover a week of rent and the intake fee, according to Colamesta.

Smaller houses may have six members, but larger houses can have a dozen or more. With profit as a motive, officials and recovery house owners describe unscrupulous or even exploitative situations.

“I’ve had many calls about one house where there are many women out at the end of the street and they’re doing sexual favors in cars,” said Longhitano. Other complaints include active drug use in the houses or cramming people into houses, far above fire code limits.

The Bucks County Recovery House Association enforces its own standards on members, but its only method of punishment is to kick out members that don’t adhere to the rules.

Regulatory vacuum means zoning fights

“If I’m a Realtor and I have to be licensed, just to sell you a home, and my hairdresser has to be licensed to cut my hair … why is it that people that own these recovery homes, that have people at the most fragile stage of their lives in their hands are not licensed?” said Longhitano.

That leaves local governments, including Bristol Township and its neighbors, to lean on what power they have to try to keep residents and those in recovery safe.

Their first line of defense are inspections, but — in Bristol and elsewhere — they are rare unless something goes really wrong.

“Once you have an OD, then you can go in there and shut them down,” said Longhitano. “We had another one that had a fire. This was all in the past couple months. We could go in and take them down.”

Some states, including Florida and California, have passed laws calling for voluntary certifications. But they are still plagued with high-profile cases of exploitative owners getting kickbacks for enrolling their clients in a certain treatment center or for demanding sex from women in their houses.

So far, state agencies have shown no interest in stepping into the role of regulator.

The Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs “licenses and regulates treatment providers and there is no treatment provided at a recovery house,” said Jason Snyder, department spokesman. Housing is viewed as separate, he said, and would not fall under his department’s purview.

Zoning restrictions are another tool that many small municipalities in Lower Bucks are using to restrict where or how many recovery houses can open up.

These kinds of ordinances don’t have a great track record in front of a judge, according to Michael Allen, a lawyer specializing in disability rights.

“I can’t think of a Pennsylvania case where any of those restrictions was upheld,” he said. “The difficulty is, you need to have someone with the capability of litigating those claims.”

Small municipalities still pass zoning laws that may violate the federal Fair Housing Amendments Act, which protects those in recovery from housing discrimination, under the assumption that there isn’t enough will to challenge them, said Allen.

Bressler, who lives at Acceptance House, said the concerns about too many or unscrupulous houses shouldn’t overshadow the good work that many do.

“It’s helping a ton of people,” he said. “And that’s what people need to remember.”

In 2014, Pennsylvania appointed a task force to come up with guidelines for certifying recovery houses, and state Rep. Tina Davis, D-Bucks, has written her own bill to create a system for voluntary regulation. Efforts to pass similar bills in previous years have gone nowhere.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.