The unexpected family, a tangle of beautiful threads

When a surprise half-sister shows up for dinner, the family around your table is not what anyone could have predicted.

Relatives of the author play a game called Knots on the day after Thanksgiving. (Image courtesy of Anndee Hochman)

A cloud of bats. A congress of salamanders. A mischief of mice.

But what do you call the crowd — three generations variously roped by blood, legal imprimatur, and choice — who gathered around the Thanksgiving table on my partner’s side of the family?

For the record, the group included:

- My youngest brother-in-law, with his wife and two daughters.

- Another brother-in-law, divorced, with his partner and two grown sons.

- One lesbian couple (yours truly) and our teenage daughter.

- A half-sister, unknown to my partner’s family until six months ago, when adoption records were unsealed in the state of Washington, enabling her to track down the adult children of the woman (my mother-in-law) who became pregnant at 20, was shipped out West to live with relatives, relinquished her baby to a couple who owned a kosher bakery and (nearly) took the secret with her to her grave.

- That half-sister’s husband, the daughter they raised from age 12 (child of their Honduran housekeeper, who died), and her daughter, who got along swell with my nieces.

- One aunt (OK, not technically) who was taken into my mother-in-law’s childhood family as a foster daughter after her parents were killed.

We were Jews and non-Jews, aged 11 to 70-something, hetero and queer, legally married and domestically partnered, conceived with intention or by happenstance, in the usual way or with donor sperm shipped cross-country in a box of dry ice — and brought together, in this wondrous and troubled time, by desire, diligence, and luck.

Maybe we should write a little note to the queen.

I mean Elizabeth, who, despite her professed approval of her grandson Harry’s engagement to the American actress Meghan Markle (“The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh are delighted for the couple and wish them every happiness,” the Royal Family tweeted), may opt to sideline herself from the wedding ceremony because the Church of England believes that marriage is for life.

The Queen and The Duke of Edinburgh are delighted for the couple and wish them every happiness. https://t.co/aAJ23uSbao

— The Royal Family (@RoyalFamily) November 27, 2017

Markle is divorced. She’s also biracial — daughter of a black mother and a white father — and will be the first non-white person to join the royal family in modern history. She and Harry are in plentiful company, though; about one in 10 people in the U.K. are in racially mixed relationships. (In the U.S., in 2015, 17 percent of all weddings performed were interracial.)

‘Life changes’

In case the queen or any of her compatriots are having quiet conniptions about that, I’d like to tell her about my mother. Thirty years ago, my mom spent the better part of an afternoon weeping in a car parked outside the Pharmacy Fountain café in Portland, Oregon, distraught that her only daughter was a lesbian, that I would never have children (surprise!), that she and my dad wouldn’t walk me down a petal-strewn aisle to stand under a wedding chuppah.

A few years later, she offered a pained apology for those tears. “I had dreams about how your life was going to be,” she said. “But life changes. You get other dreams.” In 2014, she raised a champagne flute to my legal marriage; now, she speaks on panels promoting adoption by LGBTQ parents.

It’s the job of each generation to put their elders’ assumptions to the test. Kids go to school — or even to the corner — and come home bristling with ideas. They rattle the family foundations. They confound everyone with their passion for turtles or Buddhism or anime.

Then they grow up, leave home and, maybe, fall in love with foreignness — someone whose accent, gender, religion or skin shade is different from the partner their parents imagined. Holidays get tricky, for a while. But in time, the interloper becomes kin: He makes his mom’s famous enfrijoladas; she teaches the whole clan to play mahjong. The family stretches and sprawls and reconfigures itself, and the world tips a little on its axis.

Love remakes us. Not always: Some can’t manage the leap. They slam their doors on difference and exile the beloved stranger from their tables.

But nearly everyone I know has a story running counterpoint to that scenario: a once-bigoted Nana smitten with her half-Filipino grandbaby; a trans-phobic uncle who gradually came to understand his queer niece. A mother-in-law who, despite (or perhaps because of) her own long-buried secret, embraced her lesbian daughter and her non-Jewish daughters-in-law.

Love remakes us

It was love — and the furious activism it lit — that finally put an end to miscegenation laws, that forced a decision on marriage equality all the way to the nation’s Supreme Court. It is love that kicks open long-sealed doors: in the home, and in the public realm.

In this wondrous and troubled time, when each new White House utterance makes me want to scream, I actually found some words of Donald J. Trump with which I had no dispute. “The happiest people I know are those people who have great families and real values,” he wrote in “Crippled America: How to Make America Great Again,” published a year before he became president of our fractured nation.

Great families. Real values. For me, those include radical inclusion, the precise opposite of Trump’s xenophobia, self-absorption, and race-based fear. A kind of inclusion that starts small, as we pass around the table the blintz casserole (brought by the just-found half-sister) and the teriyaki tofu (for the vegetarian daughter-in-law) and the vaulted apple pie (specialty of the divorced brother), then ripples outward, transmuting into empathy and alliance and change.

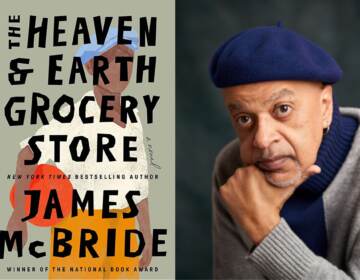

The day after Thanksgiving, our clan gathered in a park to play knots — a game in which players form a circle, hold out their arms, then grasp hands with two others who are not standing next to them. The goal is to untangle. When you’ve succeeded, after a raucous few minutes of bumping hips and ducking under the bridges of others’ raised arms, you’ve got a circle again — with some people looking toward the center, some looking out, and everyone still hand-in-hand.

The day after that, my daughter and I sat in a café near Golden Gate Park with four teenagers she was meeting for the first time: her half-siblings, all conceived with sperm from the same donor. Five kids, six parents, plates of scrambled eggs and furrows of laughter: What is the word for this constellation, for the zigzagging connections that stab us with gratitude and give us hope, in spite of it all, to hold on?

A dazzle of zebras. A parliament of owls. An astonishment of family.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.