Todd Rundgren’s ‘Something/Anything?’ celebrated with a 50th anniversary charity tribute album

Proceeds from the ‘Someone/Anyone?’ tribute album will benefit the Spirit of Harmony Foundation started by Upper Darby’s favorite son.

Listen 7:05

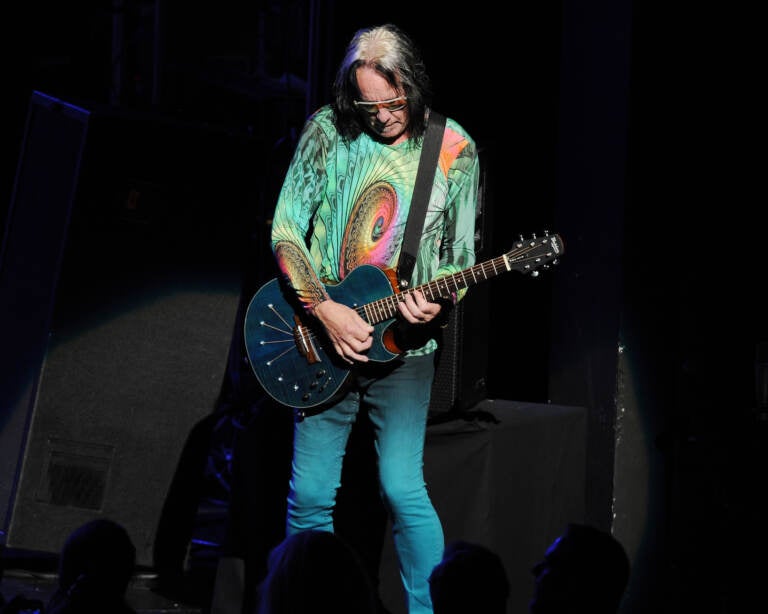

Todd Rundgren performs at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts on October 21, 2014, in Ft Lauderdale, Florida. (Photo by Jeff Daly/Invision/AP)

Todd Rundgren is a singular figure. A Rock and Roll Hall of Famer who has largely rejected rock stardom — he skipped his own induction in favor of playing a show in Ohio — Rundgren is widely considered to be a pioneering musician and producer across a wide spectrum of genres.

His 1972 double album, “Something/Anything?” for which Rundgren wrote, produced, and played all the instruments on three of the four sides, is a staple in record collections of both hardcore audiophiles and ’70s pop enthusiasts.

On Tuesday, a tribute album called “Someone/Anyone?” is being released to commemorate the album’s 50th anniversary. Proceeds will benefit Rundgren’s Spirit of Harmony Foundation.

Rundgren is known for his constant artistic reinvention and his contributions to technological advancements in music production. But before all that, he was just a kid struggling to find his identity while growing up in Upper Darby. Born in 1948, Rundgren described his upbringing in one word: bleak.

“I grew up in a postwar housing development just outside of West Philadelphia. It was called Westbrook Park. It was a typical sort of Philly/Baltimore area row housing development,” he said in an interview last week with WHYY News. “There’s nothing special about Westbrook Park.”

Even though his father, Harry, was not formally educated, he had a deep appreciation for classical music and show tunes. Rundgren said that exposed him to “more sophisticated musical ideas than maybe some of my peers.”

“The one thing he didn’t like was pop music after the ’50s. He did not go for that rock-and-roll thing. And for the most part,” Rundgren said, “would not have it played in the house.”

Rundgren always had a natural instinct for music, and could pick out melodies by ear at a very early age. But as he began to develop his own musical tastes, he said, he couldn’t afford to buy the latest hits from his local record store. So he made due with whatever esoteric discount records he could find.

“Eastern European electronic music and old live jazz shows that probably they only made maybe 200 records of, and things like that,” he said. “And it gave me opportunity to explore a broader range of musical genres.”

Rundgren described himself as a loner in his teens. In addition to obsessing over the Beatles and Rolling Stones invading the airwaves in the 1960s, he became infatuated with the Philly Soul playing on his local radio station.

He said the records spun by the “Geator with the Heater,” legendary Philly radio DJ Jerry Blavat, were ultimately his biggest musical influence growing up.

“He would play the hits, but he would play R&B records that other stations were less inclined to play. I think that accounts for the fact that so many white kids out of Philadelphia tried to sing like Black kids,” Rundgren said. “Just because we were exposed to the music in a way that maybe in some other cities, especially south of Philadelphia, they never would have experienced.”

After graduating Upper Darby High School in 1966, Rundgren moved to Philadelphia and began making a name for himself in the Philly blues scene with his band Woody’s Truck Stop. He left after eight months, shortly after bassist Carson Van Osten and before they released an album, growing disillusioned with playing the blues.

Rundgren and Van Osten began recruiting members for a new group: the Nazz (or, just Nazz, depending on whom you ask).

“We schemed up this band and we went out and stole a drummer from another band, and the singer from another band, and more or less put together Philly’s first supergroup,” he said. “And everyone was interested in it because it was the best of all of the local bands.”

The Nazz were managed by the owner of a local record store, who put the band up in a house in a “newly gentrified part of South Street near the Schuylkill River.” Shortly thereafter, the band got “so-called discovered” after watching The Who in concert in Philly.

“We’d heard that they were staying at the Holiday Inn downtown. So we went down to see if we could meet some of the guys, And we found Roger Daltrey in the bar,” Rundgren said. “We were dressed up like we always dress up, like we were in a band. And [one of The Who’s managers] approached us and says, ‘Are you in a band?’”

The Nazz auditioned the next day, and the band was quickly “whisked off to New York.” Its Brit pop-inspired sound caught on in Philadelphia and beyond, with many mischaracterizing the Nazz as being from across the pond.

“That may have contributed to some degree of the popularity we enjoyed in a city like Cleveland … They kind of like, they fell in love with us because they thought we were English,” Rundgren said. “Then, you know, later realized that we weren’t, we were just from the other side of Pennsylvania.”

The Nazz put out three albums in a year and a half before Rundgren quit because of the band’s constant infighting. Mostly, they fought about their lack of shows. Rundgren said their manager, John Kurland, had a theory that “the more you played, the cheaper it was to get you to play.”

While living in New York City and involving himself with the Greenwich Village music scene, Rundgren got a job engineering albums for Bearsville Studios founder Albert Grossman, the notorious manager of acts like Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, and The Band. Rundgren became known as a production wunderkind of sorts, engineering albums like the Band’s classic “Stage Fright.”

No fear of failure. Then, success

After becoming a much in-demand producer, Rundgren wanted to return to being a performing artist. And after releasing two solo albums, he began work on “Something/Anything?” in 1971, at just 23 years old.

Rundgren wrote and produced every song and played every instrument on three of the four sides of the 26-song double album. He didn’t fear commercial failure, since he had his production career to fall back on if the record flopped.

“That liberated me from a lot of the concerns that other artists had regarding success. In other words, I was never going to starve because I could always make a record for somebody else,” he said. “And so I never went into the studio with the idea that, ‘Oh, this has to be commercial success or I’m done.’”

“Something/Anything?” included the hit songs “I Saw the Light” and “Hello It’s Me” — a reworking of a tune he wrote with the Nazz that became a Top 5 hit. It would also be the biggest of his career.

“The original was very dirgy — morose, even. And so I thought there would be another way to do it that would make it sound more contemporary and maybe less dirgy and depressing,” Rundgren said, adding that he composed a new arrangement of the song “more or less on the spot,” despite (to this day) not knowing how to read music.

The album was a massive critical and commercial success that catapulted Rundgren to stardom.

On its release, Village Voice critic Robert Christgau wrote, “The many good songs span styles and subjects in a virtuoso display … And the many ordinary ones are saved by Todd’s confidence and verve.” The album was eventually listed as one of “The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time” by Rolling Stone.

The success of the album led to comparisons to other singer-songwriters of the early 1970s, like Stevie Wonder and James Taylor, which Rundgren resented, “with all due respect to Carole King,” he said. Instead of inspiring him to make more commercial records, his success further cemented his personal ideology of making music he found interesting, regardless of commercial success.

“That has been, and will continue to be, the operating principle upon which I make my decisions about what to do,” he said.

A tribute, a true cause

Fernando Perdomo, a longtime session musician and music producer, is one of many who cherish “Something/Anything?”.

“What other Top 10-charting album can you think of that combines hit songs with experimentation over two sides?” he asked. “The thing that made Todd different than every other hit artist in the ’70s is that you never knew what he was going to do next.”

Feb. 1 marks the 50th anniversary of “Something/Anything?”. To commemorate the occasion, a tribute album has been released, called “Someone/Anyone?”.

Perdomo spearheaded the tribute album, which features artists such as Stan Lynch, the original drummer for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, and Kasim Sulton, bassist in Todd Rundgren’s Utopia.

Perdomo said he put the album together as a labor of love.

“It’s an album that’s designed to pay tribute to the songs … This guy has inspired all of us. This music has been the soundtrack of our lives,” he said. “We would all be different people if it wasn’t for this album. So we’re giving back.”

In the spirit of giving back, proceeds from the album will benefit Rundgren’s Spirit of Harmony Foundation, which helps underfunded music programs, mostly in public schools, secure the resources they need to provide quality music education.

The founding of Spirit of Harmony was inspired by a “fan camp” Rundgren did for kids in New Orleans right after Hurricane Katrina.

“They had lost a lot of instruments. They were still recovering. They didn’t have money to pay counselors or teachers or anything. So the fans got together and got up a collection. They collected $10,000, and then we made up a big novelty check and we went down to the Ninth Ward, and the kids played a little show for us and we gave them the check,” Rundgren said. “The fans were all there, and they all got so warm and squishy about the experience. They started to beseech me about, you know, establishing something permanent.”

Spirit of Harmony chairman Ed Vigdor said the foundation functions as a conduit between programs and fundraisers.

“Todd has referred to us as the eharmony of music education. It could be, you know, strings or it could be instruments … whatever it is,” he said. “They say what they need, we try to see if we can hook them up with the resource that can help provide that stuff for them.”

Spirit of Harmony provides assistance to Play On Philly, which provides music education to underserved child musicians, and was working with the Upper Darby Arts and Education Foundation before the pandemic forced them to scrap their plans.

Rundgren said he made the decision to keep fundraising goals small.

“We were not going to measure our success by the size of our bank account or the number of our fundraisers,” he said. “We would only fundraise enough to cover our operating expenses, and we would make our strength be our ability to network and to connect entities together to identify a need and then connect it with a solution.”

Looking back, Rundgren said, he’s happy the album that propelled him to stardom 50 years ago still endures.

“I was part of, I guess, a singer-songwriter movement, even though I didn’t adhere to the same sort of rules. There’s something about that era in the ‘70s … that still has some charm for people.”

You can make a monetary donation, or donate an instrument, to Spirit of Harmony by visiting the website here. You can also purchase the “Someone/Anyone?” tribute album here.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.