Thousands of Pa. voters disenfranchised?

Listen

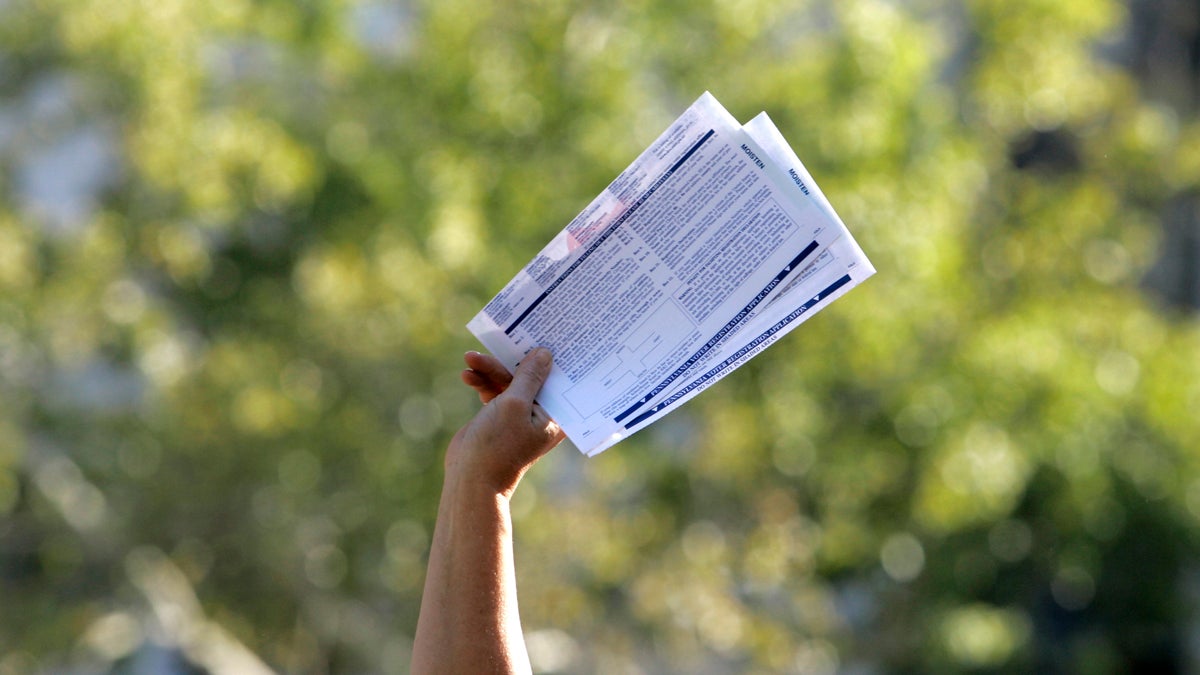

A new report finds that thousands of Pennsylvanians who filed voter-registration applications such as these last year may have been unable to vote in the presidential election because the applications weren't processed quickly enough — or at all. (AP file photo)

Thousands of Pennsylvanians who filed voter-registration applications last year may have been unable to vote in the presidential election because the applications weren’t processed quickly enough — or at all, according to a new report.

The report, by a coalition of groups called Keystone Vote, said the biggest problems occurred in Philadelphia. Nearly 26,000 people were “potentially disenfranchised,” the report finds, 17,000 of them in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia Election Board co-chair Al Schmidt said Monday he couldn’t respond to the report because it didn’t provide its source data or methodology.

“We have no idea where they are getting their number from,” Schmidt said in an email.

He has a point. The report is a little confusing, and it’s hard to tell exactly on what some of the claims are based.

But I spoke to some of the participants, and it seems there’s enough there to be concerned about whether Philadelphia and some other counties are up to the job of processing voter-registration applications.

What happened?

There’s no allegation of partisan tampering or Russian hacking here, just bureaucratic failures that could have disenfranchised people.

The report tells two kinds of stories. There are troubling anecdotes from groups that turned in registration forms that seemed to go nowhere.

Wei Chen of the group Asian Americans United said he personally handed in 37 completed voter application forms to the city in July, months before the election. He asked the guy across the counter for his name, so he’d have some point of contact.

When none of the applicants appeared in the state’s online voter database after several weeks, Chen followed up with city election officials. They couldn’t find the applications or any record of their submission.

“You know, those forms just disappeared,” Chen told me. “We couldn’t find any of them.”

Chen had scanned the applications and re-submitted them.

Former Penn Law student Glen Forster said he followed up on applications for 83 Penn law students he’d submitted. When he followed up later with election officials, he found that 15 percent never yielded registrations.

In four cases, city workers incorrectly entered the material in the state voter data base, he said. In nine others, the applications were lost, or the material entered so incorrectly they couldn’t be traced.

[NOTE: An earlier version of this story stated incorrectly that Forster had photocopied the applications. Though other non-profits whose experiences were described in the study did photocopy applications submitted, Forster simply kept the names of the students’ applications he submitted and asked election officials to look them up later.]

The big numbers

The assertion that 26,000 may have been disenfranchised comes from the second kind of information in the report — an analysis of processed applications done by the Philadelphia Public Interest Law Center.

Statewide, 55,708 voter registration applications weren’t processed by their county boards of election until eight days before the election, the center found.

Forty-six percent were then added to the rolls, but that was too late for many voters to get a registration card in the mail, and too late for them to appear in the main voter rolls that are distributed to polling places.

That 46 percent is the nearly 26,000 the report says “were potentially disenfranchised.”

They were presumably eligible to vote, but many may not have voted because they hadn’t received their registration cards and didn’t find their names in the statewide database.

Others could have shown up at the polls and hoped election workers would see they were in the supplemental lists of newly registered voters, since they wouldn’t be in the main voter rolls. Or they could cast a provisional ballot and hope it would count.

There’s no information about how many of those 26,000 voted, or tried to vote, but the report said failing to process their applications in timely fashion put their votes at risk.

One person I spoke to, Penn law student Estee Ward, had to cast a provisional ballot which was never counted because election officials couldn’t locate the application she submitted.

Pat Christmas of the watchdog Committee of Seventy said the findings are clear enough.

“It seems clear that on a systemic level, counties around the state, but particularly Philadelphia county have big problems processing voter registration applications,” he said.

What next?

I have to note that it’s not easy for county election boards to handle a flood of registration applications in the last few days before the deadline, 30 days before the election.

But it’s their job, and it’s critical to a functioning democracy that they do it well.

Changes would make a difference — some involve better technology, others improvements in the state election code.

Election officials should sit down with the authors of the report and have a constructive conversation about what happened, and do better next time.

State response

I received this response from the Pennsylvania Department of State, which oversees elections:

“We are reviewing the findings in the Keystone Votes report and will continue our ongoing work with the counties to identify ways in which processes can be improved.

“The Keystone Votes report confirmed a key belief of Governor Wolf and the Department of State – that Online Voter Registration (OVR) is the single most effective way to ensure that voter registration applications are received and processed in a timely fashion. With OVR, there are no incomplete or illegible application forms. With OVR, citizens can track their application as it moves through the verification process. Moving forward, wider use of the Department’s new OVR Web API will greatly mitigate the problems encountered with traditional paper-based applications used in most voter registration drives.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.