‘They put me in solitary for having oranges’ — incarcerated Muslims struggle during Ramadan

A lawsuit in Franklin County highlights challenges faced by incarcerated Muslims during Islam's holy month.

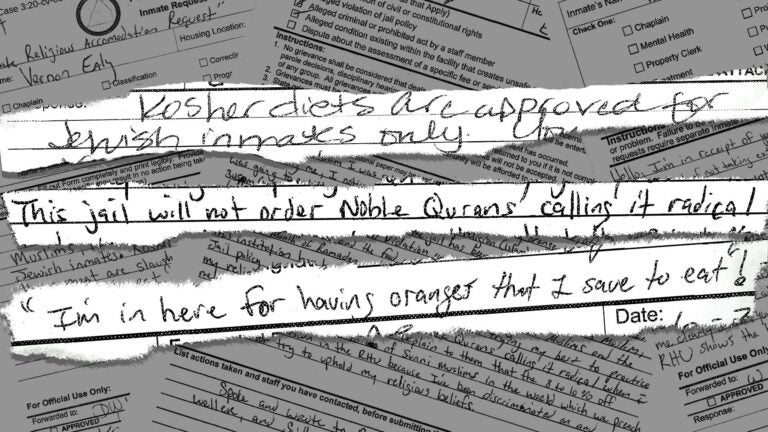

Photo illustration by WITF's Tom Downing Excerpts from grievances filed by incarcerated Muslims held at the Franklin County Prison. (Tom Downing/WITF)

This story originally appeared on PA Post.

Muslims around the world began the annual celebration of Ramadan on April 23. The month-long observance requires followers to fast during daylight hours, a practice that demands discipline and careful planning.

But religious rights groups along with civil rights attorneys say that people incarcerated at correctional facilities across the state are regularly prevented from properly observing Ramandan. And with coronavirus protocol in place at all correctional facilities, they say observing it has become even more difficult.

In Franklin County, Vernon L. Ealy, Jr., a 44-year-old incarcerated Muslim who also acts as the county prison’s unofficial imam, filed a lawsuit in January based on multiple grievances he filed against the jail last year. Those grievances allege that corrections officers failed to deliver food during non-fasting hours, put him in solitary confinement for trying to keep oranges in his cell, and denied all incarcerated Muslims access to their preferred versions of the Qu’ran, Islam’s holy text.

Ealy, who is still incarcerated, says that the problems brought up in his lawsuit have continued during this year’s Ramadan, which is set to end on May 23.

The question at stake in Ealy’s case is whether or not the jail is violating incarcerated Muslims’ right to practice their religion without undue burden. The Religious Land Use and Incarcerated Persons Act, passed in 2000, says that correctional facilities must provide appropriate religious materials and attempt to meet all religious needs of inmates. If they don’t, it’s on them to prove they can’t provide the accommodation.

“When it comes to religious rights, it’s the one area where Congress has explicitly recognized that people on the inside have the same rights as those on the outside,” said Alexandra Morgan-Kurtz, managing attorney for the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project.

For Muslims incarcerated during Ramadan, this means jails must make arrangements to deliver meals and medications before sunrise and right after sunset. And all year, Muslim prisoners should also be provided with prayer rugs, kufi caps, prayer beads and their preferred religious texts.

In a past investigation, PA Post reported that multiple county jails do not provide free Qu’rans to Muslim prisoners, while Christian prisoners almost always are able to obtain free Bibles. And even in situations where all believers of faith are required to purchase religious materials from a prison commissary, we found that Muslims were typically charged three or four times more for Qu’rans than what Christians paid for Bibles.

In his lawsuit, Ealy says prisoners haven’t been provided a copy of the Noble Qu’ran, an English translation of the Arabic text carries the seal of approval of Islamic religious authorities. The jail responded to Ealy, saying that he would only be allowed the text they have on hand.

Ealy claims that leaders at the jail called the text he requested “radical.”

The warden and county commissioners’ office never responded to calls or emails to PA Post that questioned the jail’s policy and decisions on providing religious texts.

But Matthew Callahan, an attorney with Muslim Advocates, a legal advocacy group in Washington, DC, said that the jail is likely violating the law if they’re not providing what Ealy has been asking for. He also said this and other denials related to Muslims’ rights to practice their religion is not an uncommon problem, especially during their holy month.

Most concerning, he said, is how Muslim prisoners get their food. During Ramadan, Muslims abstain from eating or drinking from daybreak to sunset. This includes water or medications. If guards don’t bring food at the correct times, Muslims can go days without food if they hold true to their fast.

And multiple lawsuits — both in Pennsylvania and across the nation — have challenged facilities that refuse to provide the proper meals for Muslim prisoners during Ramadan.

Similar to Jewish and early Christian traditions, Islamic belief says that pork is “impure.” And just like Jewish Kosher food, any meat served must be blessed — called Halal. (It’s common for Muslims to eat Kosher meals and vice versa.)

At the Franklin County Jail, the deputy warden wrote that prisoners are “not allowed to have Kosher meals” if they aren’t Jewish.

Another person currently incarcerated at the Franklin County Jail, Devon LeGrand, also complained about not being provided Kosher meals.

Past court decisions have sided with corrections departments on this matter. In 2019, the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania said that the Department of Corrections had not violated prisoners’ religious liberties by declining to provide Kosher meals to a Muslim prisoner. The court said there wasn’t enough evidence provided by the appellant, an prisoner at SCI Mahoney, to prove that the prison substantially burdened his religious beliefs by not providing a Kosher meal.

But since then, the Department of Corrections has allowed prisoners to apply for a vegetarian, Kosher or Islamic diet, which includes fish.

“It’s discrimination,” LeGrand said over the phone. He also pointed out that meals are served during times when they can’t eat while the sun is up.

As a workaround, Muslim prisoners observing Ramadan often try to cache food delivered during the day so that they can eat it once the sun goes down or right before prayer in the morning. But storing uneaten prison food in their cells is a violation of prison policy, unless it’s bought through the facility’s commissary.

In one instance, a corrections officer wrote that guards found food — oranges, bread and water — in Ealy’s cell. He was placed in solitary confinement for contraband and not following orders.

As Ramadan still has just under two weeks left of fasting, Ealy says that he and other Muslim prioners are doing their best, but they’re growing weak and frustrated. Noting the importance of food during Ramadan, he said in disbelief, “They put me in solitary for having oranges.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)