The war after: How my great-great grandfather deserted the Union army and earned an honorable discharge

One hundred fifty years ago, Private James Early White returned home to his mother after deserting the victorious Union army. Thus began a complicated, 75-year odyssey.

One hundred fifty years ago, Private James Early White returned home to his mother after deserting the victorious Union army.

The Civil War had been over for nearly two months. Two younger brothers and a sister were dead. His remaining brother was at the state asylum. His father’s severe palsy tremors prevented him from farming the family’s 200 acres of tobacco north of the Missouri River.

White, my great-great grandfather, was 5 feet, 10 inches tall and 27 years old. He had brown hair and “hazel” eyes. He had marched 7,000 miles and fought in 28 battles. He was shot in the lip at the Chattahoochee River and struck in the head by shrapnel at the Battle of Atlanta.

Still, the U.S. government charged him with desertion, a crime that called for the death penalty. Even the governor of Illinois, a major general during the war, could not help his case.

His thousand-mile trek from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Saint Catharine, Missouri, was the beginning of a complicated, 75-year odyssey, brought to light on this sesquicentennial of the Civil War though pension records, interviews, and a pocket field diary that he kept during the war.

James Early White, is shown at the time of the Civil War. (Image courtesy of Michael Carolan)

James Early White, is shown at the time of the Civil War. (Image courtesy of Michael Carolan)

The bounty jumper

In January 1865, my great-great grandfather was in Beaufort, South Carolina. He had followed General Grant to Vicksburg and General Sherman on his “March to the Sea.” His three-year enlistment with the 26th Illinois was over. While most simply re-enlisted, my great-great grandfather’s commander told him to go home: His health was unmanageable, with chronic stomach pains and spells of dizziness, brought on by a piece of shrapnel to the head.

But James Early White didn’t listen. He had sent his paychecks home and was broke. So he went to New Britain, Connecticut, where the noted shirt manufacturer Isaac N. Lee paid him $550 to become his substitute in the 6th Connecticut.

“Most often pecuniary interests persuaded men whose terms of service had expired to seek out a new unit,” said Brian Matthew Jordan, author of “Marching Home: Union Veterans and their Unending Civil War.” “The end of the war was a maddening hour, and one riddled with uncertainty, fear, and conflicting emotions.” Oftentimes, soldiers became “bounty jumpers” — enlisting, taking the money, and then fleeing the unit.

I suspect my great-great grandfather became one of thousands of such men. He needed the money not just to return home for a few months, but also to help his father. His plan failed. The army detained him in a conscription camp at New Haven.

“I wanted to get out of there because they abused me,” he told a pension investigator years later.

Rumors circulated among the men of his former unit: He “was drunk or drugged” and forced into re-enlisting. The army meanwhile had “tied” him to a stairway to keep him from escaping.

“I told them that all I wanted was to get home to my mother and then come back,” he said.

Instead, according to records, the army took his money, $550, locked him up for 45 days, and sent him to Wilmington. On May 20, 1865, he told his new commander that he was headed home and would return in a few months. This time, the war over, the army let him.

Conflicting loyalties

By June 10, 1865, James Early White was home. He helped his father with the farm and comforted his mother over his siblings’ deaths the previous fall.

The brothers, 20-year-old Jackson and 28-year-old John William, were likely victims of Confederate General Sterling Price’s forces or of Southern sympathizers who terrorized pro-Union families during the conflict. Such sympathizers included the young outlaw Jesse James and William “Bloody Bill” Anderson, famous for hanging his victim’s scalps from his saddle, said Bruce Nichols, author of “Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri.”

Headstones in the Linhart Chapel Cemetery, Linn County, Missouri, mark the final resting places of John William White, age 28, and Jackson White, age 20, brothers of James Early White. (Images courtesy of Michael Carolan)

Headstones in the Linhart Chapel Cemetery, Linn County, Missouri, mark the final resting places of John William White, age 28, and Jackson White, age 20, brothers of James Early White. (Images courtesy of Michael Carolan)

“Some of the Missouri guerrillas were desperate men,” Nichols said. “Southern sympathizers who lived near the White family probably knew they were from Virginia. Some folks may have taken offense that the Whites did not feel allegiance to the South like others with Virginia or North Carolina or Tennessee roots.”

Alliances were notoriously complex in the border states that had joined the Union but kept the “peculiar institution” of slavery. Some wanted it abolished. Others believed in the Union, expecting President Abraham Lincoln to protect their interests (including slavery).

Then on Jan. 1, 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, setting free the three million slaves living in the Confederacy but not those in border states such as Missouri.

My great-great grandfather appeared to agree. On Jan. 20, 1863, his diary entry reads:

“Quite an exciting time about the Negro question. Some soldiers say they want to fight to free the Negroes. If I thought that what I was fighting for, I would lay down my arms.”

He was, after all, born in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, into a fourth generation of tobacco planters. But he did not lay down his arms, and he did fight for — and with — African-Americans. (His second enlistment was with the 6th Connecticut regiment, which fought with the famed 54th Massachusetts regiment of all African-American soldiers, featured in the 1989 film, “Glory.”)

Right on the Record

By September 1865, with thousands of Federal forces still occupying the South, readying for Reconstruction, James Early White returned east to the army. He stopped in Illinois — the state of his former regiment. Would the governor write a letter on his behalf?

Maj. Gen. Richard J. Oglesby, governor of Illinois, wrote a letter of pardon in the case of James Early White in September 1865. (Image courtesy of Michael Carolan)

Maj. Gen. Richard J. Oglesby, governor of Illinois, wrote a letter of pardon in the case of James Early White in September 1865. (Image courtesy of Michael Carolan)

“The boy is quite young, has been a good soldier and is very anxious to get right on the record,” wrote Governor and former Major General Richard Oglesby on Sept. 28. “I would be pleased if you would let him off with as light punishment as is consistent with the good of the service and I think that will not require a very heavy penalty.”

The army ignored the governor, and on Nov. 11 — which would much later become the national holiday celebrating veterans — James Early White was ushered out with a “dishonorable discharge.”

Coffee for tobacco

I had read about a diary left by my great-great grandfather in a handwritten genealogy passed down to me. I couldn’t find the Pioneer Family Museum in Oklahoma, where the diary had reportedly had been donated by a distant cousin. But last year, on a whim, I called the Okfuskee County History Center.

“We had the old diary out in a display case for some time,” said Center director Wayland Bishop. “There’s never been that much interest.”

Bishop had transcribed the diary and cross-checked the official battle records with the events in the diary. He loaned it to me for this story. I took it to the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester. Thomas G. Knoles, curator of manuscripts, said that it was comparable to a modern day planner.

“They were inexpensive items at stationer’s shops,” he said. “Soldiers could write their thoughts down so that they could share with family when they returned.”

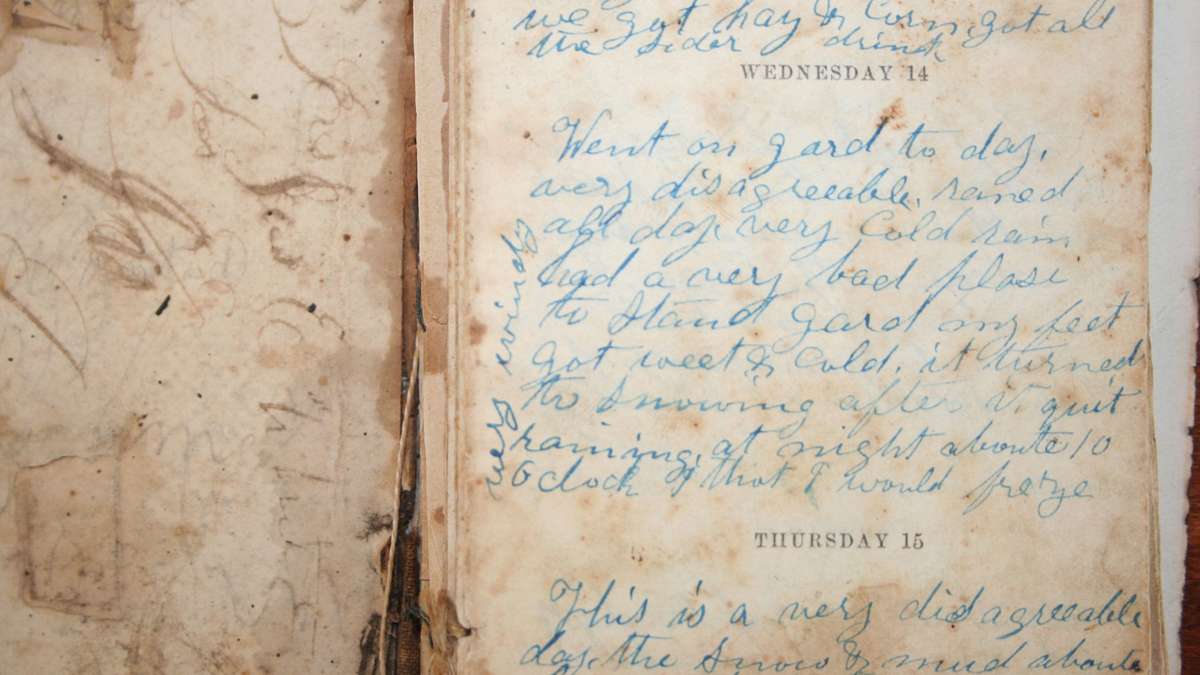

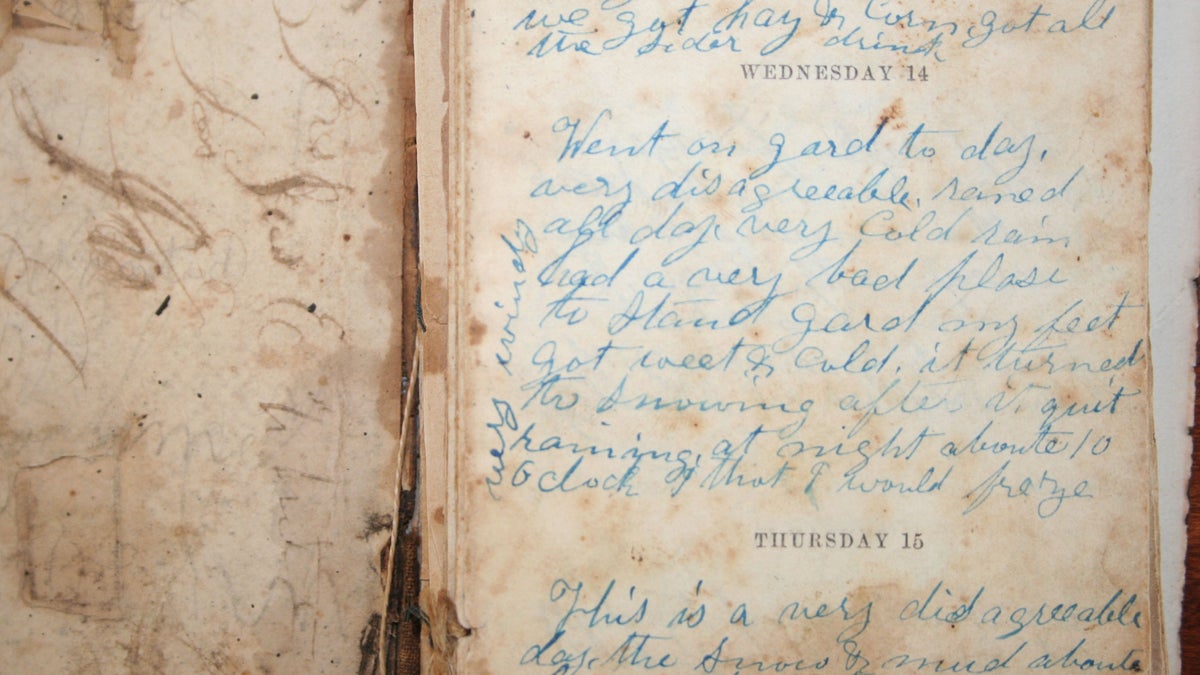

There are missing sections throughout the diary; its pages are yellowed, stained, loose or sewn together with a thread, and it is surprisingly small: five and a half inches long by three inches wide. What’s left is about 200 pages, covering the years 1863 and 1864.

Detail of a diary written by the author’s great-great grandfather during the Civil War. (Image courtesy of Michael Carolan)

Detail of a diary written by the author’s great-great grandfather during the Civil War. (Image courtesy of Michael Carolan)

I am floored to think my great-great grandfather carried the diary through the muds of Arkansas, the rains of Tennessee, the swamps of Georgia, that it was at his side while he fished the Big Black River in Mississippi, through the chaos of Atlanta.

My great-great grandfather notes when his unit gives three cheers on the first anniversary of Shiloh, when they march and how far, when it rains, when the Gens. Sherman, Grant, McPherson, Logan review them, when he is covered in dirt from shell explosions, when they forage for chickens and hogs, when they fight, and when they bury the dead.

The diary passage best showing the ambiguity of war was written during the Battle at Kennesaw Mountain, in Georgia.

Tuesday June 28 1864. Artillery was terrific all day. There was sharp musketry all day. One of our boys got shot today on the skirmish lines by a sharpshooter. The Reb’s sharpshooters get behind cliffs of rocks & conceal themselves. We can see them poke their heads out occasionally then we shoot them in the head. Our boys & the Rebs conversing to each other today on the skirmish lines, trade tobaco for coffy. We give rebs coffy & they give us tobaco in exchange.

The veteran

After the war, my great-great grandfather suffered from the health problems that plagued many veterans and filed for a pension. He was denied; the army did not reward deserters. He hired the help of a noted attorney, and on May 20, 1890, the army overturned his dishonorable discharge.

“It was often extremely hard for a veteran to track down former comrades and physicians to verify his claims,” said Will Hickox, of the history department at the University of Kansas and contributor to the New York Times’ “Disunion” blog. “It was very difficult to overturn a dishonorable discharge, as the government spent a lot of money on pensions and tried to only pay those deserving them.”

By the turn of the century, James Early White had fathered 10 children. In a family photograph, my he wears the classic long, white beard of the Civil War veteran. He is smiling, sitting in a chair surrounded by his family in front of his white clapboard farmhouse. One of those children is my great grandmother, Olive Pearl White. And so the closest I came to the Civil War in the flesh was holding the hand of the daughter of James Early White. She died when I was 9 years old.

The author’s great grandmother Pearl Olive White (1884-1975), daughter of James Early White, is shown in 1964. (Image courtesy of Michael Carolan)

The author’s great grandmother Pearl Olive White (1884-1975), daughter of James Early White, is shown in 1964. (Image courtesy of Michael Carolan)

The federal government went back and forth on whether to offer a pension to my great-great grandfather. Investigators traversed the country, taking dozens of depositions from those he fought with, lived near, or ever knew.

In 1895, federal investigator J.J. Nelligan weighed the case of James Early White in a letter to Commissioner of Pensions William Lochren.

“We might speculate and conclude that because [James Early White’s] brother was insane (through self abuse) that this claimant inherited that germs of the disease from some ancestor, near or remote, and that he would manifest a condition of impaired mind at some time in his life, if he lived long enough, whether he ever went to the Army or not. But I think that this would not be just. Were it not that claimant’s brother has been in an asylum, there is no doubt in my mind but that this wound of head would be accepted as sufficient basis for sign of the disability or disabilities alleged. As to the Hollenberg’s (a neighbor) statement that the whole White family as far as he knew are a weak-minded family, he cited no members of it except for Ben (his brother) and [James Early White]. The other brother and sister seemed to be perfectly sane. The cause of Ben’s insanity having been shown to be self abuse, and the wound had being sufficient grounds for claimant’s alleged disabilities, I think he should have the benefit of the doubt, and therefore I shall recommend the claim for admission.”

The following year, according to doctors, my great-great grandfather suffered “attacks of vertigo, convulsions, double vision, noises in his ears.” His conversations were “disjointed and rambling.” Neighbors reported that he “was not right in the head.” Three years later, in 1899, a medical board labeled him “Insane Invalid” — a condition likely called traumatic brain injury or PTSD today. Ten years later, Sept. 28, 1909, my great-great grandfather was dead. He was 72.

His wife died exactly 18 years later, to the day, in 1937. She was buried next to him, “200 yards from the front door” of the farmhouse at the Pleasant View Cemetery. Her son, Roy Ellsworth White, wrote to the government. He wanted to be reimbursed for her casket, services, vault, dress, slip and hose including sales tax, all amounting to $279.25.

My great-great grandfather’s pension file does not mention whether the claim was paid. Nor does the 385-page file reveal whether the $550 paid to him by shirt manufacturer Isaac Lee was ever returned to him.

The last document in the case file of James Early White is a letter from his son to the Veterans Administration, dated Jan. 5, 1938. Roy is 44 years old and living on the farm his grandfather purchased in 1859. He requests the remainder of an accrued pension for his mother, Carrie H. White, deceased beneficiary, for $37.33.

I suspect that the government did not reimburse the funeral expenses. In the middle of the Great Depression, Roy would have needed the money.

“Please advise me why this has not been done,” he wrote, a final query regarding the most famous of American conflicts.

—

Michael Carolan teaches literature and writing at Clark University. He is finishing his first novel, “Highway for Our God.” Michael wrote about his Philadelphia Civil War ancestor for NewsWorks in 2013.

—

Sources:

Frederick H. Dyer, “A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion.”

Charles Cadwell, “The old Sixth regiment, its war record, 1861-5.”

Illinois Civil War rosters from the Adjutant General’s Report, 26th Regiment.

James Marten, “Sing Not War: The Lives of Union and Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America.”

New York Times, “Men is Cheap,” Feb. 4, 2015.

1860 Missouri Census table.

Pension file: James E. White, National Archives and Records Administration.

Hattie Gertrude “Trudy” Lineberry, These Are Your Ancestors, unpublished.

Diary of James E. White, 1863-1864, unpublished.

Kenneth Waldo Lineberry, History of the Lineberry Family from 1752, unpublished. February 22, 1976.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.