The unsettling social media aftermath of a Philly hate crime

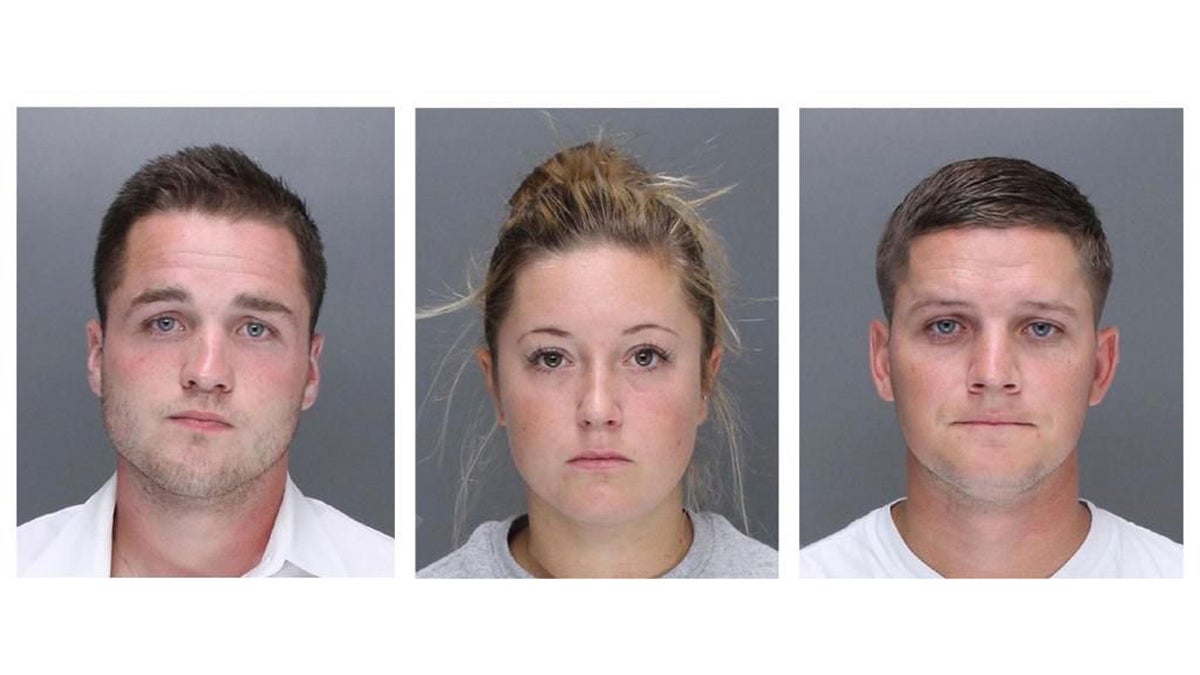

In this undated combination of images provided by the Philadelphia Police Department

A few weeks ago, watching my social media feeds, I would’ve thought my friends had scaled Mt. Everest, found a way to reverse global warming at the summit, and then discovered the cure for cancer on the way down. But it was hard to put my finger on what was keeping me from joining in the celebrations after a social media manhunt helped identify suspects in the Sept. 11 assault of a gay couple about two blocks east of Rittenhouse Square.

“This won’t take long,” my friends said as they shared a grainy surveillance video, released by the Philadelphia Police Department, of a crowd that may have been responsible for the attack.

Sure enough, within days, the Internet exploded with headlines extolling the perpetrators’ identification. My own feed filled with “we got ’em!” status updates and hopes that the suspects (referred to by many expletives I can’t repeat here) were headed to prison for a long time. It was one big digital high-five by and for everybody who, by virtue of sharing the video online, had helped take down the perpetrators of the kind of crime we hate to believe could happen here.

It was as if the case were closed overnight, when in reality, the alleged assailants hadn’t even been arrested or charged.

Many websites charted the light-speed identification: the PPD video shared alongside another photo of a suspiciously similar group of people in a restaurant, which was swiftly identified by other self-appointed sleuths. A Facebook Graph Search of check-ins from a quick-thinking Twitter user helped the police gather their leads.

Philadelphia Police Detective Joseph Murray tweeted his support for the help.

This is how Twitter is supposed to work for cops. I will take a couple thousand Twitter detectives over any one real detective any day.

— Joseph Murray (@PPDJoeMurray) September 17, 2014

And people rejoiced as if investigating and prosecuting a vicious hate crime is as easy for everyone to get in on as the Ice Bucket Challenge.

It may be how Twitter is supposed to work for cops, but is it the way we’d like it to work for the rest of us?

Innocent until …?

Without downplaying the horrible nature of the crime, in which Kathryn Knott, 24, of Southampton, Kevin Harrigan, 26, of Warrington, and Phillip Williams, 24, of Warminster are now charged, I have to say that the apparent 21st-century version of “innocent until proven guilty” — this “innocent until you are possibly spotted in a Facebook photo by self-appointed Twitter detectives” paradigm — leaves me cold.

Within a day of the social media identification, a Storify post went up for the express purpose of collecting and broadcasting all of Knott’s most rude, drunken, and apparently homophobic and racist tweets from the last three years or so. Again, my friends pounced on the chance to publicly denounce and shame the suspect, before she has even gone to trial: Here was proof positive that we had all been right from the moment we suspected that we’d spotted the carousers in that video.

But did disseminating and wallowing in that spite, however well-deserved it might be, help the victims of this crime, or help to prevent it from happening again? The heinous nature of the attack makes it all the more important that we treat it with the gravity it deserves, and respect a proper investigation by trained professionals, not roll in a week-long Internet back-slapping frenzy before we move on to the next local flash of drama and hate.

And what if, the next time a police department turns to online crowd-sourcing to hunt down the perpetrators of a violent crime, you or your family happen to be in the picture someone turns up and drapes across the Internet days before any arrest is made?

It’s happened before

If Knott, Harrigan, and Williams are convicted of this crime, I hope they’re properly sentenced. But in the meantime, I don’t want to blast each new tidbit of information that confirms my own fears and biases.

Because about a month ago, we saw the flipside of this public circus when Fox News published a video from the Ferguson, Missouri, police department that claimed to show shooting victim Michael Brown robbing a convenience store of about $50 worth of cigars just a few minutes before he died at police officer Darren Wilson’s hand.

Despite the fact that the Ferguson police department itself emphasized that Wilson had not known of Brown’s possible involvement in the alleged crime when Wilson fired his gun, many commentators gleefully seized on this viral video “evidence,” as if it somehow proves Brown, not convicted of any crime, deserved to die.

The truth is that the video of the Ferguson robbery suspect, splashed across the Internet for public consumption in the wake of Brown’s death, and the mobs of digital denizens cheering the ID of the 16th Street beating suspects as if locating them via Twitter equals an irrefutable conviction, are two sides of the same armchair vigilante gang, and we should be wary of them both.

I follow cases like this with as much revulsion as anyone who believes every citizen ought to be safe from attack regardless of skin color or sexual orientation. But until I feel sure of all the facts, I won’t be splattering extra hate around, whether it’s directed at the victims of a crime, or the alleged perpetrators.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.