The pre-existing condition conundrum before and after the ACA

Listen

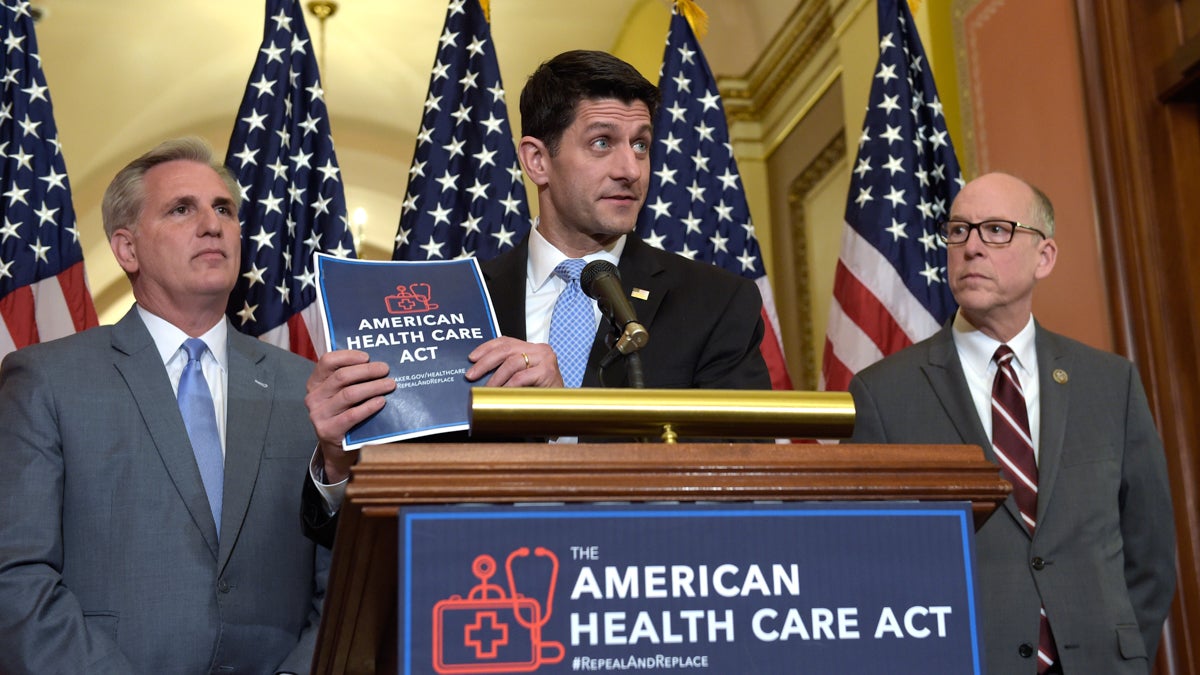

House Speaker Paul Ryan, standing with Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Greg Walden, right, and House Majority Whip Kevin McCarthy, left, speaks during a news conference on the American Health Care Act on Capitol Hill. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

As the heated debate over repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act came to a head in town halls across the country and in Congress last week, two words reverberated a lot: pre-existing conditions.

There is good reason these words keep being heard: prior to the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare), a lack of coverage for Americans with pre-existing conditions grew into a major issue. Addressing that was critical in shaping the 2010 law. As the current GOP with President Donald Trump shaped their own health care act, they were quick to reassure Americans that it’s an important issue for them, too.

“First, we should ensure that Americans with pre-existing conditions have access to coverage,” President Trump stated during his major address to Congress in February.

A proposed replacement to the ACA did not make it to a vote earlier this month, but the debate is far from over. With that, pre-existing conditions will likely remain a big part of health discussions and policies moving forward. So, how exactly did pre-existing conditions become so engrained in America’s health care crisis, and is it possible to solve?

The issue is not only complicated, but it has also been a long time in the making.

ACT I: Some health insurance history (thanks to an imperfect metaphor)

In the early days of American health insurance, pre-existing conditions weren’t overtly seen as a thing. One way to conceptualize how they fit is to turn to another arena.

“Think of the volunteer fire departments of the 19th century,” John Bertko said.

Bertko is not a fireman. He has been knee deep in insurance for a long time, most recently with the state of California’s health insurance marketplace. But back to those fire departments:

“You couldn’t put out a house fire by yourself, and so you’d contribute both time and money,” he continued. “And the community would buy a fire engine.”

Hopefully, nothing would ever happen to your house, but if it did, the trucks and hoses were on hand to help (and in reality, only a small percentage of houses would ever have major, costly fires). Bertko sees similarities to the early days of health insurance, at the onset of the 20th century. In communities around the country, the main doctor and hospital groups, the American medical and hospital associations, started up Blue Cross and Blue Shield non-profits.

These Blues, as they were called, “would take a certain small amount of money per month, and then for that amount of money, they would guarantee that a person could come in and have a doctor treat them, or they could get into a hospital and their hospital bills would be paid for.”

Pre-existing conditions weren’t overtly factored into coverage, largely because the Blues were regulated by each state as a community benefit.

“That meant that your profits were limited, but your goal would be to provide health care services at the lowest possible cost to members of the community,” said Bertko.

Ok, ok. Health insurance did have some key differences with other forms of insurance, and even fire departments, points out economist Melissa Thomasson of Miami University in Ohio. During the 1930s, health care was a small expense, for example, “nowhere near where it is today.”

Additionally, Blues started off targeting, not individuals, but rather groups of employees. The first was a teachers group in Dallas. In that way, and in her tracking of early documents related to these company formations, she argues, these insurers were eyeing the healthier working population, who’d be less sick, as a business model from the get-go.

Health insurers turned into a community benefit because, with their roots as medical providers, they didn’t have the reserves required of typical insurers. The deal they reached with states, explains Thomasson, was that they’d “agree to cover individuals as a condition for non-profit tax status.”

Around WWII, medicine was gaining a better reputation, thanks to advancements like penicillin, and with that, health care demands and the related insurance landscape took off.

The Blues were still the insurance administrators, but coverage really became defined by work. With ongoing wage controls in place, employers and employee unions negotiated an alternative benefit, one that was exempt from taxes: health care.

Again, these were big companies with lots of employees.

“And so the risk would be shared across a 1,000 or 10,000 or a million people,” Bertko said, referring to the ability to support that small percentage of people who have or would develop costly health conditions.

As an actuary for four decades, first privately and for Humana, then for the federal government and now for California, Bertko thinks a lot about risks and costs. He is basically the person tasked with trying to predict who is likely to get sick and what those costs will be in any given year. Insurers factor that in to prices.

This is a really, really hard thing to do: an underlying condition or unexpected health event is often not apparent in advance. It’s something that would further complicate and amplify pre-existing conditions in health care moving forward.

ACT II: Pre-existing conditions in a pre-ACA world

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed Medicaid and Medicare into law, the nation’s public health program for older adults and younger ones with disabilities or certain medical conditions.

It was by that time that something else was really escalating in the private insurance world.

For-profit health insurance companies gained more traction, and their model hinged on trying to identify the cheapest, or rather, healthiest groups of people to insure.

“For-profit insurance companies decided to jump in and they immediately recognized that some people were much more likely to use services, they might have some conditions already or they might be prone to have conditions,” Bertko said.

The for-profits realized they could make more money, Bertko explains, if they only covered healthy people and the people who were most likely to stay healthy.

“Yep, that’s right. And the name of that science is underwriting,” he said, referring to the practice of using predictions of who might be most likely to get sick and need costly care and factoring that into coverage options and prices.

Thomasson says beyond individuals, companies would have also been targeting companies overall which seemed to have a healthier workforce.

It’s at this intersection where pre-existing conditions really take hold. To keep up, the Blues got on board.

“So the companies [not just the Blues] started out by having a list of about 20 conditions,” said Bertko. “And these would be what I would call very, very serious conditions.”

For example: someone with cancer, or who had a previous heart attack or who has diabetes.

“But as they found out how well this worked, the list got longer and longer and more complicated,” he said.

That might have included a woman who was considering getting pregnant or someone who was obese.

“So by the 21st century, the list would be as many as 400 different conditions of varying difficulties.”

Imagine everything from high blood pressure to acne, depending on the company and the plan. A Kaiser Family Foundation study found that in general, anywhere from a quarter to a third of Americans have some sort of pre-existing condition.

By the 90s, the feds had placed protections on people who already had coverage through their work, with the passage of HIPPA. Before that, workers with chronic health conditions may have faced greater challenges. One common practice, says Thomasson, was for companies to offer health insurance to new employees that would exempt coverage of the related health condition during the first three months to a year of employment. Additionally COBRA, established in the 80s, gave people who ended their employment for whatever reason the option to stay on their work-based coverage, unsubsidized, for up to 18 months.

Still some Americans, anywhere from four to eight percent, according to Kaiser Family Foundation studies, relied on the individual market. These were the small farmers, the self-employed and people like Carl Goulden of Littlestown, Pennsylvania, near the Maryland border.

In the early 80s his situation changed overnight.

“The company I work for [for 18 years] called us all to the time clock early one morning and told us within 48 hours the entire company would be packed on trucks and moved away to Florida,” Goulden said. “So with no notice, I basically had no job.”

And with that, he had no guaranteed employer-based health insurance for himself and his family. Goulden got a temporary gig as a florist, quite a contrast from his factory work as a metal fabricator and assembler for a food packaging equipment company. He loved the change and then decided to start his own business.

“We did custom silk work, big flower vases. You bring me you your wallpaper, I’ll make an arrangement that matches,” Goulden recalled of his store, “Carl’s Creations.”

As for insurance, he went directly to the local Blue Cross Blue Shield and got a small business plan that covered him and his family. Without being part of that big employer pool, it was a bit of a sticker shock, he recalls, but business was good and he managed.

But then “about 10 years ago, my house caught fire.”

Not literally (Goulden agreed to play along with our imperfect fire department metaphor), but after a series of unusual symptoms, including fatigue and jaundice, Goulden was diagnosed with chronic liver disease, Hepatitis B. It was a complete surprise. Then he realized his work years ago as a member of the volunteer fire department might have been the cause.

“This was before the time of breathing masks when we did CPR, or gloves,” Goulden recalled. “We treated open wounds with bare hands, so I was in constant contact with body fluids.”

(Under some insurance plans, occupations like firefighters would have been factored into insurance underwriting.)

Goulden says the specialty drugs helped manage his condition but cost thousands of dollars. His insurance covered it. But then, he says, some unexpected things started happening during the annual policy signups.

“The insurance renewals went way up,” he said.

The cost of those renewals kept going up, while covering less. Eventually, Goulden says it became unaffordable and he had no choice but to drop his family’s insurance.

“I was devastated because I didn’t know when my liver might fail,” he said. Liver transplants are one of the costliest procedures in health care, costing tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars.

When Carl Goulden unexpectedly lost his job, he had to figure out what to do for health insurance. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

According to John Bertko, Goulden’s experience was not uncommon.

“Many companies, whether Blue Cross Blue Shield companies or for-profit, did similar things over the last 20 years or so before the Affordable Care Act.”

States addressed those who fell through the cracks of insurance in different ways, such as through the creation of so called high risk pools. But for individuals without employer-based coverage who became sick or developed a chronic health condition, their situation could be tenuous.

ACT III: The Affordable Care Act

The health insurance industry and the role of pre-existing conditions once again hit a major point in 2010, when then President Barack Obama signed Obamacare into law

“This year, tens of thousands of uninsured Americans with pre-existing conditions, the parents of children who have a pre-existing condition, will finally be able to purchase the coverage they need,” Obama stated.

The law meant people like Goulden couldn’t be denied coverage or face hefty price increases because they had a health issue. It also required plans to cover certain things (this is what’s become known as essential benefits). The idea was this major change in insurance could work for insurers, so long as young, healthy people also signed up for coverage, in order to create a large enough pool of people to spread the risk. This is where the whole individual mandate stems from: buy insurance or face a fine.

“In general, when you have a voluntary insurance system, adverse selection is a problem. You’re more likely to participate if you have a health need. You can cure adverse selection [when only sicker people enroll] a couple ways: one is by subsidies if you make [insurance] cheaper or free for people to participate,” said Karen Pollitz, a researcher with the Kaiser Family Foundation.

She also points to the challenges and lessons learned from when Massachusetts changed its health system and became one of the frameworks for the ACA. The other way to address this issue and create a bigger pool of people is through mandates.

“Just make people go in.”

Still Tom Miller, an insurance expert with the D.C.-based think tank, the American Enterprise Institute, worries the ACA placed too much emphasis on pre-existing conditions.

“The preexisting condition issue was used as a marketing device in order to sell a lot of other policies,” Miller said.

The issue, he says, is that healthcare is just expensive for everyone. Those with really costly pre-existing conditions comprise a small piece of the pie. He thinks this emphasis on pre-existing conditions in the ACA deflected that bigger problem and created other ones. For example, not enough healthy people enrolled, some markets lost money and the premiums went up.

“When you make insurance much more comprehensive and also try to hide the price of that insurance and the costs of it from as many people as possible, thinking that it will somehow be financed below the table, then insurance as a market breaks down,” Miller said. “And the question is what type of mangled political mess we’re going to try to live with in order to hide more costs and subsidize more people, and find taxes to pay for it.”

Miller says one option for now dealing with pre-existing conditions are high risk pools. These were around pre-Obamacare in some states, as a state insurance option for people who couldn’t get affordable care because of a pre-existing condition.

Pollitz could not disagree more. She says states who tried these pools faced major challenges. They cost a lot, both for the state and for the patient. And in many states, “the one that usually surprises people is that these state high risk pool programs would exclude coverage for the preexisting condition that made you eligible in the first place.”

This wasn’t a permanent thing, but it often meant necessary care for a health condition, like those $1,000 health meds – the ones Goulden needed for his Hepatitis B would require waiting six months to a year before the pool would cover it. Bertko recalls huge backlogs when he was involved with California’s high risk insurance program.

“At one point in time there were another 10,000 people on a waiting list,” he said. “They may or may not have gotten in, but we only could have funding for 20,000 people at any given point in time.”

Pollitz acknowledges the ACA has had growing pains. A lot of healthy people didn’t sign up. The current fine of about $700 wasn’t a big enough stick. And even with the options of federal subsidies, coverage for some people was still unaffordable. At the same time more chronically ill people, like Goulden, signed up (after enrolling, he experienced an unanticipated heart attack. He fully recovered, and was glad to have coverage for upwards of half a million dollars in care).

Pollitz was hopeful the rough transition for insurers would smooth out in the coming months and years.

“[The ACA] was transformative. It completely changed the nature of the individual health insurance market,” she said. “It completely changed the business models of insurance companies.”

The uninsured rate is also way down, as is the rate of national health spending. Employer based premiums have risen at slower rates than they did before the ACA was enacted.

ACT IV: Repeal and replace

The ACA is at another turning point now. President Donald Trump and Republican leaders of Congress campaigned and took office on the premise of repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act.

Although the GOP’s recent efforts to replace the law did not gain enough support to make it to an important vote, leaders have emphasized that pre-existing conditions will be covered in any kind of replacement. That latest proposal also had its own version of the individual mandate incentive – a surcharge of about 30 percent on people who don’t sign up for continuous coverage. There was a section creating a federal fund for states to use in a number of ways, from providing extra support to insurers who cover more patients with pre-existing conditions (also known as reinsurance) to bringing back high risk pools.

“High risk pools are a smarter way to guarantee coverage for people with preexisting conditions,” House Speaker Paul Ryan touted at a CNN town hall in January.

Even though the plan has been tabled, the challenges of managing pre-existing conditions don’t appear to be going away. One issue that keeps coming up is what will insurance cover and how will that be paid for.

“In the years when we’re sick, we need help paying for it,” Pollitz said. “So one way or another, we have to find a way to pay for it.”

So how will this affect Carl Goulden? Actually, he just turned 65 and moved into a different neighborhood of coverage. It’s a big one that pretty much everyone pays into and then joins:

“Medicare is a pretty reliable fire company,” said Goulden. “I haven’t had any trouble at all.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.