Are you on the front lines of the coronavirus? Help us report on the pandemic.

Jeff Dodgson organizes so many burials now he sometimes doesn’t realize an acquaintance has died until he is preparing their final resting place.

“People I’ve known from working here for so long, people I would see a couple times a year, or people I would plant flowers for,” said Dodgson, foreman of the Glendale Cemetery in Bloomfield. “I’m out marking a grave, and I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, this was Mrs. So-and-So.’”

The cemetery Dodgson operates in Essex County, one of the hardest-hit areas in a state pummeled by the coronavirus pandemic, is doing three times the number of burials it typically would.

He said the pace of work and the new dangers presented by COVID-19 have heaped added stress on his staff and himself.

“I’m kind of the back end of the frontline workers,” he said.

Since the pandemic took hold in New Jersey, doctors, nurses, and paramedics have scrambled to treat the tens of thousands of patients who have become ill with the virus, battling both physical exhaustion and the mental anguish of witnessing the outbreak up close.

The same goes for those who work in the state’s “death care” industry — funeral directors, cemetery staff, clergy and even some police officers.

“We’re working as hard and smart and trying to do our best as the frontline folks are,” Kurt Larsen, manager of Volk Leber Funeral Home in Teaneck, said.

He went on, “We’re busy. We’re overwhelmed. We’re always working, 24/7,” when his colleague interjected.

“We would really love some recognition!” she shouted.

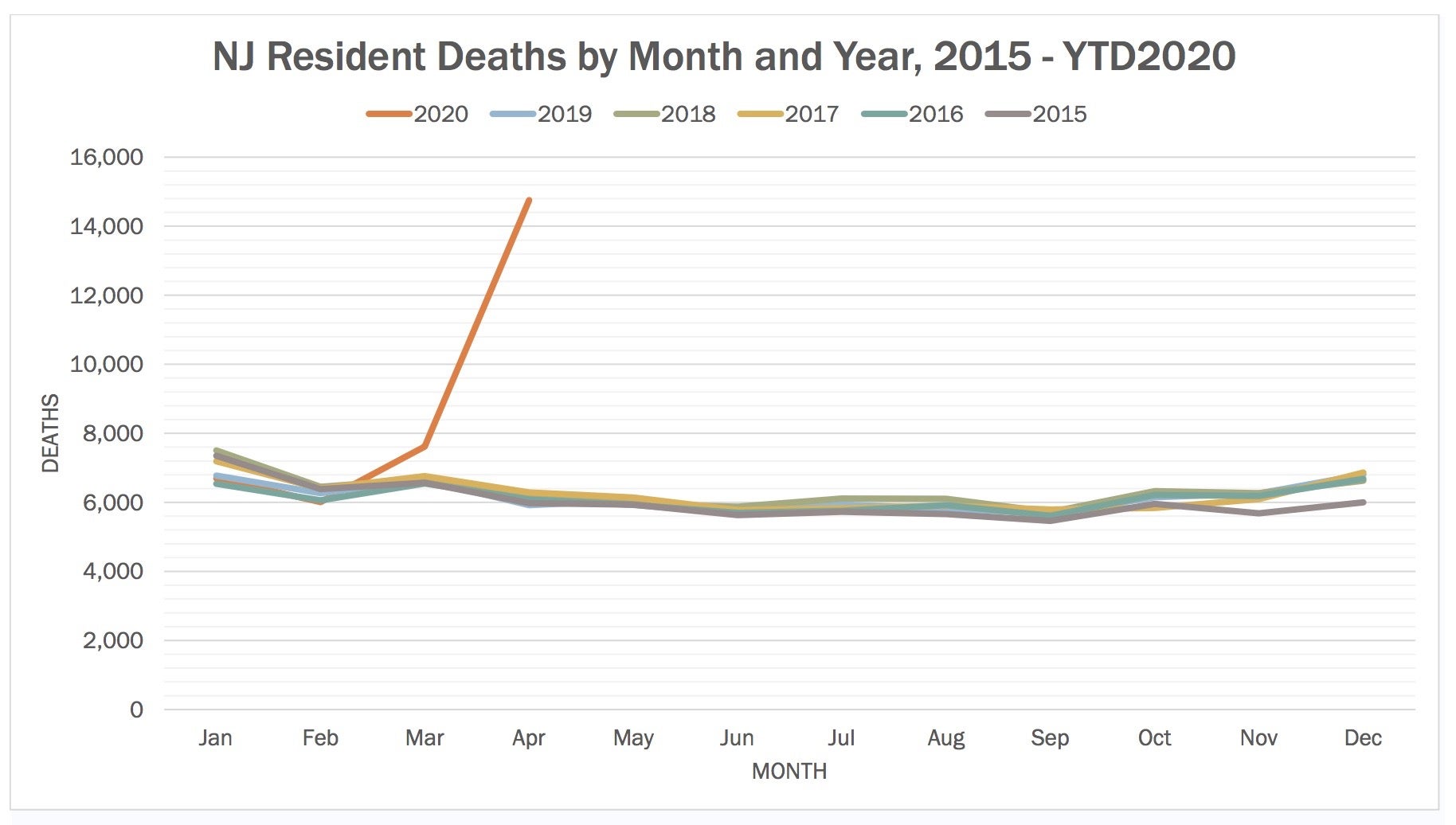

An estimated 6,000 people pass away in New Jersey every April. Last month 15,449 residents died — a stunning 254% increase.

Funeral homes and cemeteries accustomed to handling a certain number of deaths per week were suddenly facing two or three times that. The state’s roughly two dozen crematories faced a three-week backlog, causing bodies to literally pile up at morgues in hospitals and funeral homes.

To relieve some pressure, the state last month sent several refrigerated trucks to a temporary morgue site in Newark, where State Troopers and National Guard soldiers provide oversight.

State Police Superintendent Col. Pat Callahan said those operating the facility have a tough job.

“It’s not a normal thing to go through, to open up a tractor-trailer and see the remains of 82 people,” he said.

It’s not just that the pandemic has caused demand for mortuary services to soar. The highly transmittable nature of COVID-19 has also brought about emotionally painful changes to how end-of-life services are conducted.

Funeral parlors can no longer hold open-casket ceremonies and have had to stop hosting in-person viewings, per a recent state order. Many cemeteries now limit the number of people who can attend a burial, if one is held at all.

Some families are live-streaming services for mourners who could not or were not permitted to attend in person. The once intimate family affairs have gone, like many other parts of life under quarantine, remote.

Dodgson, for his part, used to escort grieving families around his cemetery. Now, he sends them videos he made of himself strolling the grounds pointing out available plots.

Such changes have gutted families struggling to mourn a sudden and tragic loss, but they have also impacted the psyche of death care workers, many of whom say they got into the business to provide comfort and support to people enduring the worst days of their lives.

“This is not what we signed up for,” said George Kelder, executive director of the New Jersey State Funeral Directors Association. “We signed up to be caregivers. Now we’ve simply become order-takers.”

Last month the National Funeral Directors Association wrote President Donald Trump asking him to issue an executive order identifying death care workers as essential critical infrastructure personnel. Part of the reason, the association said, was so death care workers could secure adequate personal protective equipment to deal with the bodies of people who died of COVID-19 and be around family members who may have contracted the virus.

In New Jersey, at least two funeral directors have died from complications of COVID-19, though it is unclear how they contracted the disease.

Judith Welshons, executive director of the New Jersey Cemetery Association, said managers of death care facilities are taking new steps to protect their staff from COVID-19. But those measures can often confuse or even insult families trying to bury a loved one, such as limiting in-person visits to 10 people or fewer.

“It’s almost like the families are shell-shocked. I’m not accusing them of deliberately defying anything, but they wouldn’t even think about [the fact] that they shouldn’t be going to a funeral home,” Welshons said. “It’s not comfortable for anybody on either side.”

For many death care workers, the psychological trauma of witnessing the fatal pandemic up close may be what causes them the most harm in the long run.

Col. Callahan has repeatedly noted during Gov. Phil Murphy’s daily briefings the need to support those who work in ‘mortuary services,’ who are being forced to witness an unprecedented surge in deaths.

The state Department of Human Services has provided crisis counseling to EMS and first responders. Crisis counseling for disasters, like the current pandemic, is also available to the public.

But Callahan said the emotional toll on death care workers may not reveal itself until well after the dust has settled, likening the delay to a developing photograph.

“Right now we’re in such head-down, nose-to-the-grindstone mode that when it ends, and you kind of take a breath, that’s when the photo really develops,” he said. “Even for me personally, I think that’s gonna happen.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)