Temple class guides participants through tough options for end-of-life care

Listen

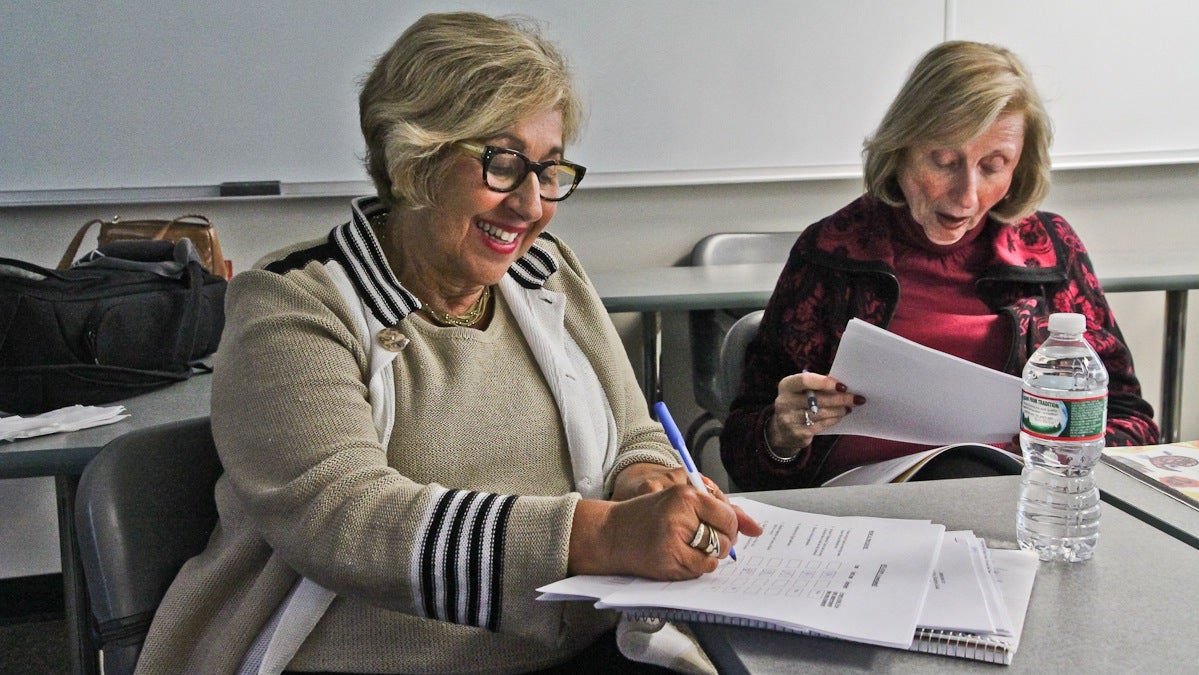

Barbara Greenspan Shaiman fills out a survey of what she would for herself should she be unable to direct her medical care. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

A recent Institute of Medicine report called “Dying in America” called for an overhaul of end-of-life health care in the U.S. It noted high costs and unnecessary procedures, and also found that most people do not receive the kind of care that reflects their wishes and values in the last months and weeks of their lives.

The majority of people will be cared for in a hospital by a doctor who doesn’t know them, stated the report, which calls on Americans to actively plan what kind of care they want to receive as they are dying.

Death is a tough and perhaps even taboo topic for many people, and a class a Temple University’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute guides students through these challenges step by step.

“None of the above” was not an option on the forms Mark Peterson handed out to his students during a recent Monday afternoon session in his four-week seminar. Instead, the group of seniors gathered in a sun-lit classroom was mulling over tough situations with even tougher options. For example, what kinds of interventions would they like to receive if they were in a coma with no hope of recovery.

Barbara Shaiman of Bala Cynwyd quickly checked off the boxes on 12 options.

“This is a scenario where there is no hope, so all I would want is No. 12, which is pain medication,” she said. “I don’t want surgery, or antibiotics, nothing else.”

Shaiman, who is in her 60s, looks perfectly healthy and fit with a nice sun tan. She decided to take this course after losing her parents, husband and a step-daughter within five years, which gave her a sense of wanting more control at the end of life.

“Death is an inevitable act of life, and if we’re prepared for it, maybe it’s not as frightening,” she said.

Peterson guides conversations around different decisions, the group reads articles together and watches videos. But that’s only half the work.

“Then we take a look at how they can make presentations of their decisions to their family as well as their physician, the two most important people ensuring their voice is heard for the rest of their life,” he explained.

Peterson, who spent his career as an educator, developed this course after reading about terrible experiences patients and their families have at the end of life.

One of the obstacles that gets in the way of having one’s voice heard is family quarrels when the patient is cognitively unable to discuss wishes, Peterson said.

Shaiman has not told her friends or children that she is taking this class yet.

“I’m sure they won’t be happy,” she said with a chuckle. “But I’m doing it a lot for them!”

She said she doesn’t want her children to be faced with tough choices on her behalf during a time of stress and grief.

Once all the paperwork is filled out, and participants have named proxy decision-makers who can take over their care decisions if they become unable to do so themselves, Peterson said, they still have to “talk, talk, talk” about their wishes.

He said the more people communicate about their wishes for end of life care, the better their chances are to die they way they had intended to.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.