Study on targeted medicines shows different front of cancer battle

Researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia are reporting success with a new targeted anti-cancer therapy. Experts say the small study shows the ways doctors are fighting cancer differently.

For some conditions, there are now anti-cancer drugs that zero in on DNA-level miscues that allow cells to grow uncontrollably. A targeted medicine from drug-maker Pfizer Inc.has been successful in fighting a particular kind of adult lung cancer. Researchers thought the drug, called crizotinib, might also work in children against aggressive and uncommon types of lymphoma and neuroblastoma.

The researchers weren’t sure what dose of medicine might work best, so as a first step, Children’s Hospital oncologist Yael Mosse and the team signed up children in urgent need of another option.

“These are patients that, by the time the physician talks to them about a Phase 1 trial, it means there’s no known cure. It means they’ve had all the best available treatment that we know of in the year 2012,” Mosse said.

The study was conducted by the Children’s Oncology Group, a network of researchers across the country looking for novel and less harsh ways to treat childhood cancer.

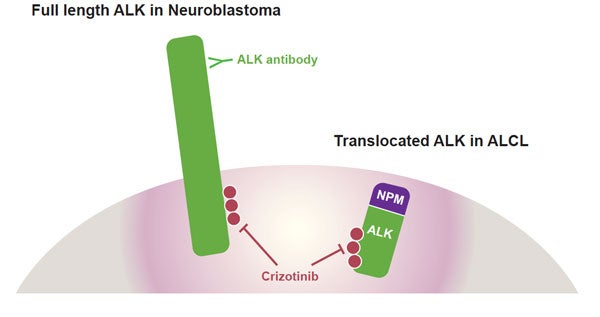

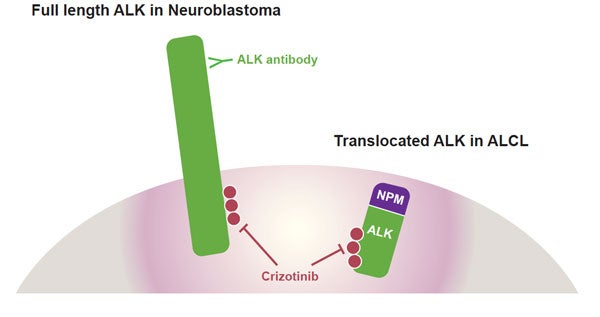

When it works, crizotinib latches on to, and shuts down, a gene called anaplastic lymphoma kinase. The scientists call it ALK.

Rearrangements in the DNA or breaks in ALK can ignite and promote cancer.

In some cases, Mosse can now tell her patients not only that they have cancer, but an ALK-driven cancer. That subsetting, she says, points the way for drug developers.

“So if you find what’s driving the cancer, you hypothesize, that if you turn it off, it will have a significant impact on slowing down, or turning off the growth of the cancer,” Mosse said.

(Graphic courtesy of CHOP graphic designer Angela Knott)

Utilizing lock and key

Drug developer Robert Sweetman searches for ways to explain how the drug binds with the ALK gene.

“Cut off the fuel line … other people use an analogy where it’s a lock and key. Where crizotinib is the key and where cell growth is being driven is the lock, and it goes in there and turns that off,” Sweetman said.

Sweetman’s company Pfizer supplied the medicine used in the trial. He says there’s a trade off in developing targeted anticancer medicines such as crizotinib, or brand-name Xalkori. While they offer new hope for fighting cancer with fewer side effects, they are useful for a smaller number of patients.

The Children’s Oncology Group study was small – just 77 patients. But Sweetman says with a targeted medicine, preliminary successes are more promising.

“We are becoming more intimate with the tumor on a molecular basis. We’re more comfortable with this early data when we have these very precise targets and very precise drugs,” he said.

So far in, the results have been most promising in the children with anaplastic large cell lymphoma. After treatment, doctors could not detect cancer in seven of the eight kids. Some children experienced easy-to-control nausea, while others had some liver irritation when the medicine dose was high.

“That’s all we’ve seen for now,” Mosse said. “There’s not been any hair loss, the blood counts stay pretty much normal. Patients don’t need blood or platelet transfusions the way they do with traditional chemotherapy.”

Zack’s story

John Witt’s first-grader Zachary was one of the seven whose cancer went into remission after crizotinib treatment.

“It’s dealt with the lymphoma quite nicely without doing other things to him,” Witt said. “The drug is made to go after the tumor but not to affect all the other cells of the body, that’s how they explained it to us. Apparently that’s what’s going on here.”

The Witts live in Berks County. In 2010, they helped Zachary through the tough side effects of standard chemotherapy, but the cancer came back. Then doctors suggested crizotinib and the Children’s Oncology Group study.

“Even though experimental sounds a little scary, the expectation would be minimal and manageable side effects,” Witt said.

Zack’s mom, Pam, says it wasn’t hard to take a gamble and participate in the study after her high-octane son relapsed and was admitted to the hospital.

“He would just say: ‘I want so much to go to the playroom.’ But he’d say: ‘I just need to rest first.’ Then he’d sleep all day. He just had no energy to get down there,” Pam Witt said.

She noticed a difference just days after Zack started the targeted therapy. “I opened the door and he just flew out around my legs and ran down to the playroom,” Pam Witt said.

His mother says Zack is doing well now, loves basketball, likes playing the card game Uno and just learned to write in cursive. He’s fuzzy on the facts about lymphoma but knows the medicine helps him feel better.

“Every day, I take two pills twice a day, supper and breakfast, and the next day I keep doing that,” Zack said.

Study leader Yael Mosse says doctors will monitor Zack and the other children closely.

“Indefinitely. That’s paradigm shifting. In the past, the average time kids with relapsed cancer have stayed on investigational drugs is one to two cycles. We’ve now have patients on for two years,” she said.

Watching, waiting

No one knows how long the medicine will work, says Susan Blaney, a pediatric oncologist at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

“Developing targeted therapies sounds easy, but the body is very, very smart. And just like bacteria develop resistance to antibiotics, cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy or targeted therapies,” said Blaney, one of the leaders of the Children’s Oncology Group collaborative.

“Our ultimate hope is that we can avoid some of the long-term side effects that are associated with traditional anticancer therapy,” she said.

While the progress with ALK-targeted treatment is encouraging, Pfizer drug developer Robert Sweetman says the tests and medicines for children are not widely available.

“It’s not become routine yet, but this is how routine starts,” Sweetman said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.