Stonewall changed Mark Segal from invisible Philly gay kid to visible gay rights advocate

Jennifer Lynn speaks with Mark Segal, publisher of Philadelphia Gay News, about his participation in the Stonewall Riots of 1969.

Listen 6:54

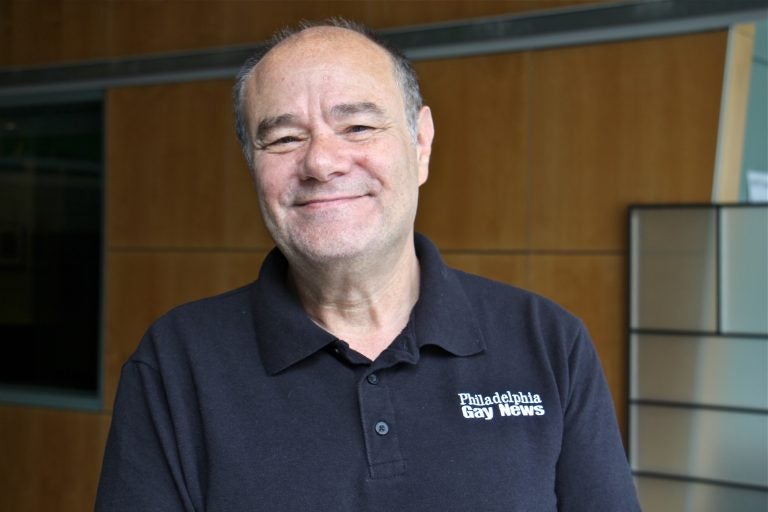

Mark Segal, publisher of the Philadelphia Gay News. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Those who witnessed the police raid at the Stonewall Inn in New York City 50 years ago today say that singular event at a popular gay bar was life-changing for themselves and for gay people in America — that it touched off the gay liberation movement and led to gay rights.

Mark Segal, publisher of Philadelphia Gay News, was there. Morning Edition host Jennifer Lynn discusses his path from invisible gay kid growing up in Philly to visible gay rights advocate — and what it means to publish the newspaper.

—

I had the opportunity of walking over here with my husband and my puppy. We obviously look like a couple with our little dog, or a family in a sense.

Right, so there was a time when you really couldn’t do that. Even just walking by yourself was uncomfortable.

Oh, absolutely. I left Philadelphia, a city of 1.6 million, because I didn’t believe there were any gay people here when I was 18 years old. That’s why I went to New York, and that was six weeks before Stonewall. I went to New York to be with my people.

Remember your young self for us at 18.

Oh, I mean there are pictures of me at 18 at various demonstrations in New York. I was adorable. I had hair; I was skinny. Much different than what I am today.

What were you into?

Well, you went to New York to be yourself, to be free. And I didn’t know how much of that you could be because, after all, when I was growing up in the 1960s, we were invisible. You didn’t see us in newspapers. There were no radio interviews with gay people. You didn’t see us on TV. There were no characters, no LGBT anchors. We were nowhere. If you wanted to find out who you were once you figured out who you were, you might go to a library and you might find, maybe, five books on the subject. But each of those books told you you were immoral, illegal, told you that you were mentally ill. And that was it.

You moved to New York. Did you go to school? Were you living with friends?

Well, I told my parents I was going to school in New York. Although when I went there, I had literally no plans, no nothing, actually.

You made friends.

Oh, immediately. You didn’t know where gay people were in New York, but you just thought, possibly, there is a place called Greenwich Village, and all the beatniks and hippies went there. So you figured, if unusual people could be there, and I certainly was unusual being what I was, at least I thought maybe I’d find gay people. So the first thing you do is get on a subway, go to Greenwich Village, and there’s no neon sign saying, “This way to the gay people!” So, you look around. The minute I found Christopher Street, it was nirvana. I had found my people. And that became my life every night, walking up and down Christopher Street all the way to the Stonewall. At the end of the night, you always went to the Stonewall. It was the only place in New York where you could go and dance, and 18 years old, you want to dance.

What kind of kid were you? Were you an activist or were you just living large enjoying yourself? What were you like?

I think I have to talk about my grandmother, Fanny Weinstein. Why I’m doing what I’m doing today is her. As a young kid, she used to tell me about her family and the pogroms in Russia, which were anti-Semitic. And to my grandmother and family we’re living in a Jewish village, and as she says, if the Cossacks came and destroyed the village, and they wanted to escape that kind of life, they came to the United States. As a young girl, she became a suffragette and fought for the right for women to vote. And when I was 13, she took me to my first civil rights march with Cecil B. Moore around City Hall.

But moving to New York, was that part of an agenda of any sort? Catching on to a wave of any kind of activism, or were you simply there?

OK, so there was no real “gay movement.” What there was is, once a year in Philadelphia from ’65 to ’69, about 40 people would march around City Hall or in front of City Hall. That was it. I lived in Philadelphia. I never heard about them. That explains to you the invisibility that we were. Up until what we did with Stonewall and gay liberation front, the movement in America was no more than 100 out people. Think about it: 1969, not more than 100 out people in the entire country. It’s sort of amazing. So, the riot’s happening, and sometime during that night, I was standing across the street, and something in my head clicked. I thought about what my grandmother said, and I realized: Blacks are fighting for their rights. Women are fighting for their rights. Latinos are fighting for their rights. What about our community? Or, what about me? And I decided right then and there that’s what I was going to do for the rest of my life. And that was sort of unusual in the sense that there was no thing called being a “gay activist.” So I didn’t know where my life would end up. I thought I’d end up being on the street.

You’ve worked for the Philadelphia Gay News as an editor.

I don’t have the brains to be an editor.

Sorry, publisher. Let’s end on this notion of the pen being mightier than the sword and what it means to you. And you have a voice and you’ve been visible through this newspaper.

One of the things we did which was revolutionary when the paper came out, its name itself was visibility: Philadelphia Gay News. We got vending boxes and we plastered stickers on them: Philadelphia Gay News. We wanted that to be visible. We wanted people to think about us every single day when they passed those vending boxes. We now have over 100, many boxes around Center City and West Philadelphia and other locations in the Delaware Valley. They’re there for people who are just coming out, who they walk by them and they go, “Hmm …There might be something about me in that paper, something that I can utilize.” Or it might be for an activist who might have different views than what the paper has, and we give that space so they can give their views. It’s a communication platform for our community, and it also informs the community of dangers. Best example of that was during the HIV crisis. We were the place that people had to turn to because publications like The Inquirer just didn’t do it.

Good luck carrying on. Thank you.

Thank you. Lovely being here as always.

And you know everybody here. You’re quite visible at WHYY. I couldn’t get down the hall without you high-fiving and hugging. What’s up with that?

Well, because you were one of the first media, mainstream media in America to really take us in and let us talk on the airwaves so people could see we’re not that monster in the closet. They realized that we’re flesh and blood. We’re your sisters, your brothers, your uncles, and your aunts and your cousins. We are literally everywhere, and you should get to know us. Get to know us. You won’t be frightened of us.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.