SEPTA funding conundrum: just riding Act 44 isn’t enough

Dec. 14

By Anthony Campisi

For PlanPhilly

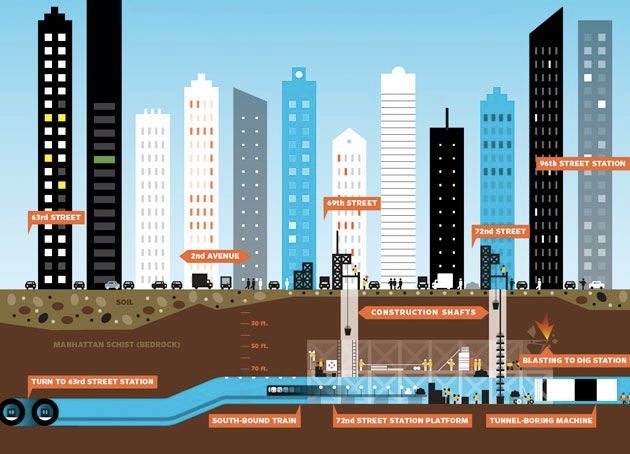

In 2007, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in New York began construction of the Second Avenue Subway, a dream of city planners more than 75 years in the making.

In 2002, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority opened its Silver Line trackless trolley line.

Want to see a new transit line in Philadelphia? Try coming back around 2016.

While state transportation officials are working to save Act 44 — the legislation that provides SEPTA with a dedicated source of funding — by pushing for federal permission to toll Interstate 80, what’s less talked about are the law’s limitations.

Because the act only provides enough money to restore highway and transit agencies up to a state of “good repair” — and sometimes not even that, according to transit planners — there’s not a lot of money for major system overhauls. In fact, according to the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, SEPTA will have only $1.7 billion through 2025 for system expansion projects.

(If you think that’s a lot, consider that the new rail tunnels New Jersey is building to Manhattan are expected to cost $9 billion.) This means that there’s simply no money to contemplate major SEPTA expansion projects, like extending the R8 Fox Chase line out to Newtown.

Money for that and other projects will have to come from sources other than Act 44 and existing federal transit programs.

Local funding options

The Philadelphia region currently contributes a small proportion of transit funding nationally. The city and its four suburban Pennsylvanian counties provide 7 percent of SEPTA’s annual operating budget. One way to bring that contribution up would be to assess dedicated local taxes to transit funding.

Many regions are funding or have funded transit system expansions through the levying of taxes to raise the capital costs incurred in building a new line.

Denver is a prominent example of this, paying for its FasTracks expansion, which will construct six new rail lines with 199 miles of track, in part through a region-wide sales tax increase.

Vukan Vuchic, a transportation engineering professor at the University of Pennsylvania, said that voter referendums to fund system expansions through increased taxes pass about 75 percent of the time.

Peter Haas, education director for the Mineta Transportation Institute at San Jose State University, said voters tend to be willing to pay taxes to transit. However, his research has shown that they are more likely to support taxes that go toward funding a specific improvement and have a sunset provision — a five-year tax to fund a new light rail line, say, instead of a tax to cover system-wide operating expenses indefinitely.

While referendums are more popular out west, Charlotte, N.C., has successfully passed referendums on capital improvements and Tampa, Fla., is considering a measure, Haas said.

Yet Denver and Charlotte are not Philadelphia.

SEPTA, along with other older, extensive transit systems, requires billions of dollars a year just to keep the current system running.

Federal stimulus money, for example, is going to replace power subsystems that are almost a century old.

And because the region has such an extensive transit system, it’s almost impossible for it to qualify for New Starts money, the federal program that subsidizes other systems’ expansion projects.

There’s hope in the planning community that the new transit reauthorization, which the Obama administration has put on hold while it tackles health care reform, will provide new sources of funding for established systems that can’t produce the ridership gains that newer systems can promise. That hope is underlying funding expectations for the proposed light rail line along the Delaware River.

Though the project isn’t expected to qualify for New Starts money, Chris Jandoli of Parsons Brinkerhoff, the consulting firm hired by the Delaware River Port Authority to help plan the line, said that he hopes the federal government will look to the line as a model project for innovative sources of federal funding.

That funding could be based on the projected economic benefits the line would bring to the waterfront and could be funneled through the Department of Housing and Urban Development, he explained.

Regional roadblocks

But federal funds won’t solve the local funding problem, which is complicated by restrictions placed on counties’ ability to impose local taxes, according to Leo Bagley, assistant director of the Montgomery County Planning Commission.

The suburban counties rely on real estate taxes for funding, which don’t provide enough revenue for major capital projects.

Only Philadelphia and Allegheny counties have the power to levy a sales tax, which would bring in more money. Those increases also require state approval, which, as Mayor Michael Nutter recently discovered, is hard to get. The state also has restrictions on referendums for transit funding.

“It’s a pretty difficult state to do large projects in,” Bagley said. He sees the way forward through funding measures pushed by both transit and highway interests. Individually, they don’t have enough clout to push something through the legislature.

Bagley is banking on that support for a plan he’s pushing to alleviate congestion along Route 422.

The plan, currently under study, would involve tolling the highway and using that money for highway upkeep. Extra revenues would be used to fund an extension of the R6 regional rail line along the corridor, which would hopefully take commuters off the road and put them into trains.

Don Shanis, deputy executive director of the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, said that the intermodal component of the 422 plan is the reason why his organization is strongly supporting it.

Tolling schemes like that are effective, he said, because they directly charge the people who are benefiting from transit improvements. A county- or region-wide sales tax, on the other hand, can garnish opposition from people who are taxed but won’t be taking advantage of the new transit options the money is paying for.

Shanis also said that innovative public-private partnerships may be important for future capital projects. As an example, he cited a transit line that would be built at the same time as a shopping mall. The mall would provide the impetus to build the line, which would in turn support the mall by bringing in shoppers and employees.

(Bagley pointed out, though, that current state law makes establishing public-private partnerships difficult.)

At the same time, system expansion might not be the best use of capital dollars, Shanis said. The DVRPC’s goal in its long-range plan is to work on making the core system as user-friendly as possible, not to promote sprawl by extending transit lines out into the exurbs. He pointed to the SEPTA smart card system as a good example of that type of capital investment.

A question of political muscle

The question remains, though, whether there is political will at the state level to push through legislation to empower the region to increase capital spending. Bagley doesn’t think Harrisburg will touch the issue until at least a year or so into the term of the next governor. While Shanis is cautious against making a similar pronouncement — he argued that it’s easy to continually find excuses against doing something — he did say that transit funding isn’t anyone’s No. 1 priority. “People get it, but not enough to fund it,” he said .

Shanis said that the DVRPC and transit officials could do more to push for projects.

A good step, he said, would be to reduce the number of projects on the region’s long-range plans. The Delaware River tram, for example, which would connect Philadelphia with Camden, is still on the DVRPC’s list of projects even though serious efforts at construction have been abandoned.

He said that it’s a diffusion of energy and resources to include projects, like the resumption of trolley service along Route 23, that no one believes will happen. Shanis also said that the region should be lest risk-averse and more willing to accept the occasional failure in pursuit of larger goals.

It’s that type of thinking, he said, that has led SEPTA to leave most of the political heavy-lifting on the R6 extension to the Montgomery County Planning Commission. The authority would like the project to be completed but isn’t going to risk embarrassment if it fails.

Ultimately, however, “I don’t think … transportation is in control of its own destiny,” Shanis said. He believes that transportation funding will ride on a larger societal decision about what to do in the face of increased competition from the developing world: Either the United States will decide to make substantial investments to remain competitive or it will fall into a long, slow decline.

ON THE WEB:

http://planphilly.com/node/9384 — PlanPhilly feature story on Act 44

http://planphilly.com/septa — The Newtown expansion article in PlanPhilly

The link to the DVRPC long-range plan: http://www.dvrpc.org/Connections/

And a link to a DVRPC graphic showing major capital projects through 2035: http://www.dvrpc.org/asp/connections/majorProjects/

Contact the reporter at campisi.anthony@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.