SEPTA battles Philadelphia before Supreme Court in jurisdictional war over LGBT protections (again)

On Tuesday the Pennsylvania Supreme Court heard oral arguments for the second time in a case over a now-deceased person’s complaints about a since-abandoned SEPTA policy.

SEPTA originally filed suit in 2009, making a responsive strike in what would become a war of litigative attrition between the transit agency and Philadelphia’s Commission on Human Relations.

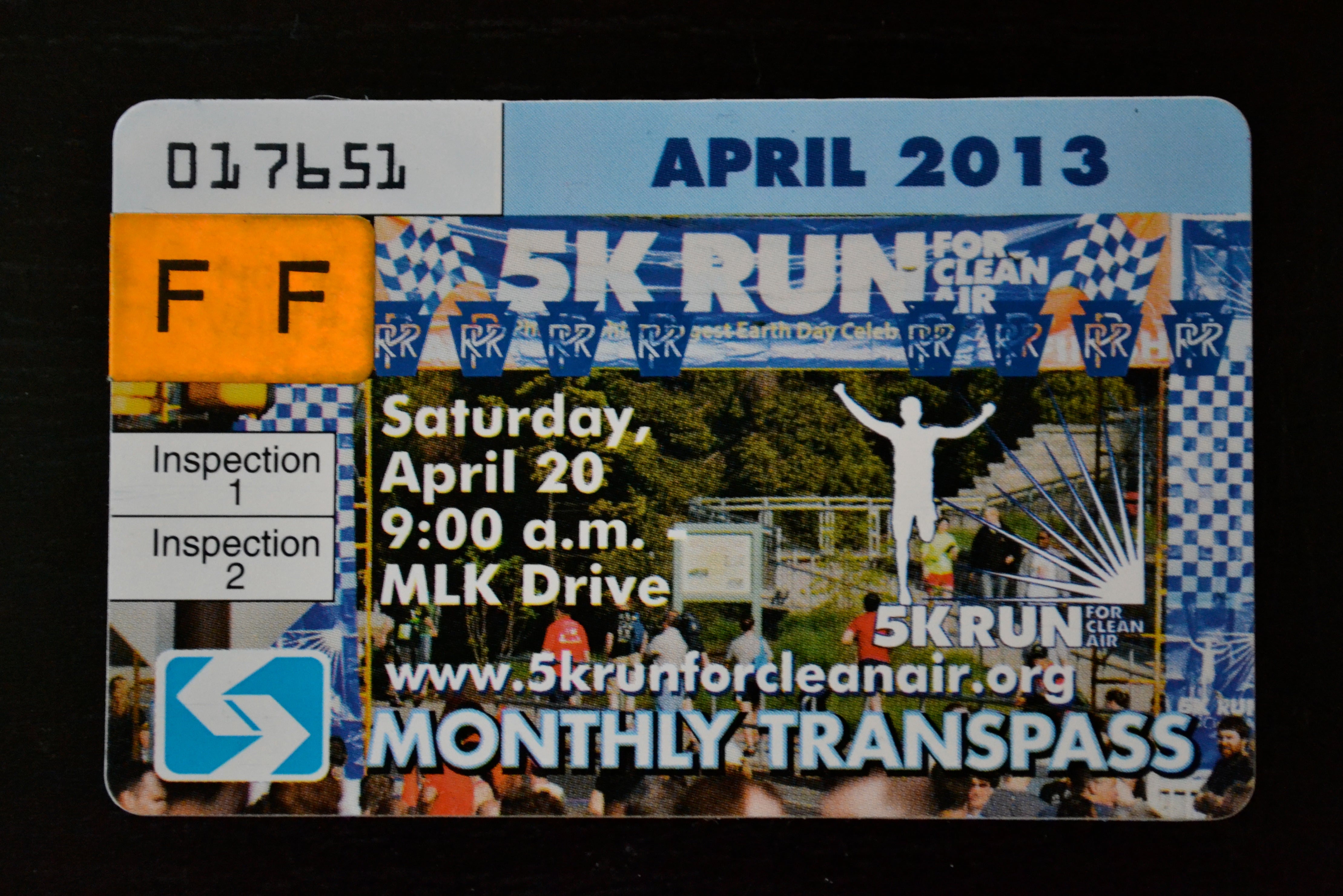

Two years prior, a transgender woman named Charlene Arcila alleged that SEPTA’s policy of indicating a passenger’s sex on their transit passes violated the Fair Practices Ordinance. The Fair Practices Ordinance (FPO) is the city’s non-discrimination law, which protects sexual orientation and gender identity—categories the statewide discrimination ban does not include—in housing, employment and public access. The Commission on Human Relations, which enforces the FPO, began an investigation of this allegation and six others against SEPTA.

In response, SEPTA sought a quick declaration that the Commission lacked jurisdiction over a state agency like SEPTA. That question — whether Philadelphia can regulate SEPTA, a state agency that operates in over 100 municipalities — has proven rather difficult to answer.

In 2010, SEPTA got an answer, but not the one it wanted: No, SEPTA did not have sovereign immunity from FPO claims. The transit authority appealed, getting the yes it always wanted, just two years later. That was followed by another appeal—this time, the court said maybe— followed by another court saying yes, then yet another appeal, and that brings us to Tuesday’s oral arguments before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which will issue a fifth decision in this case sometime over the next 12 months. That will finally put this moot issue to rest once and for all, unless, of course, the Supreme Court remands the case again to a lower court, which is a very distinct possibility that SEPTA argued in favor of on Tuesday (if it cannot win outright).

In the middle of this seven-to-nine year saga, SEPTA removed the offending ‘M’ and ‘F’ stickers from its passes, and Arcila passed away.

The original complainant and the offending policy may be gone, but after seven long years it still isn’t clear whether SEPTA must yield itself to the laws of Philadelphia, and perhaps 100 other towns, or if the next Philadelphian with a discrimination claim must go without redress if a bus driver violates rights that the City otherwise protects.

Throughout the lengthy ordeal, SEPTA has stated repeatedly that it has no intentions to discriminate and would not oppose an expansion of the state anti-discrimination laws to include LGBT protections; it’s simply a fight over jurisdiction.

In general, states enjoy sovereign immunity: You can’t sue them. Over the ages, the General Assembly has made exceptions to that rule, saying you can sue the government under certain circumstances, like when it violates the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act.

That same immunity gets extended to other governmental bodies like state agencies and municipal corporations, i.e. SEPTA and the City of Philadelphia. So while the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania undoubtedly has power over Philadelphia’s government, and Philadelphia cannot presume to tell the state what to do, SEPTA and the City are generally considered equals.

Both are considered instrumentalities of the Commonwealth: Children of the General Assembly born from the Metropolitan Transportation Authorities Act and Philadelphia by the First Class City Home Rule Act, respectively.

So SEPTA v. City of Philadelphia is a sibling squabble now in its fifth round, and like any good Dad, the Supreme Court effectively asked, “What did Mom say?”

Richard Feder, chief deputy city solicitor, argued that our matronly General Assembly hasn’t said a thing on this matter, and so it simply isn’t clear. In the immediately preceding lower court decision, the Commonwealth Court disagreed, siding with SEPTA’s assertion that SEPTA should enjoy immunity against local laws unless there is an explicit exception. Given that the Supreme Court decided to hear the city’s appeal to that decision, it seems like that it will agree with the City, at least on this one point.

Now the Supreme Court must decide how to interpret the interests of two competing state instrumentalities—SEPTA’s need to run buses, and Philadelphia’s desire to prevent LGBT discrimination—in such a way as to not frustrate either’s purpose.

In other words, it’s now just a question of whether this specific Philadelphia law can be enforced against SEPTA. Any other question about some other municipality’s ordinances against some other state agency, or some other Philly law on a different topic, would be a jurisprudential fight for another day. Or, as Chief Justice Thomas Saylor put it, “We’ll cross that bridge when we get there.”

That came in response to one example in the parade of terrible scenarios floated by SEPTA’s attorneys, each describing the horrors that would befall the transit authority should it be forced to yield to Philadelphia here: A slew of overlapping and conflicting ordinances from 100 towns would bury SEPTA’s legal department in a mudslide of regulatory compliance paperwork. SEPTA’s outside counsel, Patrick Northern, also hypothesized how SEPTA would—or even could—react if a municipality passed an ordinance banning public breast feeding, a practice protected by Philadelphia’s FPO. What then, asks SEPTA?

Feder provided a preemptive answer earlier during oral argument: When SEPTA’s in that still-hypothetical other municipality’s borders, it should follow its hypothetical laws, and when the transit provider is in Philadelphia, it should follow Philadelphia code, real or otherwise.

Both sides’ attorneys sounded willing to sacrifice a bigger win for a more probable win, arguing that the court could make very narrow rulings in their favor. For the City, that meant admitting that it couldn’t fine SEPTA for violating LGBT rights, but it could at least force SEPTA to the table for jaw sessions with the complainant, and maybe issue an injunction or two. Northern, arguing for SEPTA, said that, if nothing else went the transit authority’s way, the Supreme Court would have to remand to a lower court to develop a factual record to apply to the legal opinion it will finally issue.

The problem, of course, is that no matter who wins, both functions will survive. SEPTA frets about the slippery slopes it will fall down once subjected to dozens of local laws and the cost of that regulatory compliance. But it has managed to follow local traffic laws well enough, for one. Even if local control dominates, that means SEPTA will have to follow City A’s law in City A, and Town B’s in Town B; hardly the end of the world. The line between A and B would blur if a resident of City A takes the bus to Town B, where anti-Aism is entrenched in some invidious law, but the justices seem ready to punt on that hypothetical problem.

By the same token, the City’s limited ability to drag SEPTA before the Commission on Human Relations would hardly turn Philadelphia into a hotbed of intolerance. SEPTA has maintained throughout this proceeding that it has no desire to discriminate against anyone, and has updated its policies across the board to be sensitive to the LGBT community. Philadelphia also has two seats on SEPTA’s board and controls a veto power that the other counties do not enjoy. The mayor has his bully pulpit, and SEPTA, as a modern day corporation located in a liberal northeast city, has PR and labor reasons to avoid discrimination.

No matter who wins here, the other will get along just fine.

After arguments, Feder seemed pleased, while SEPTA’s hired guns from Dilworth Paxton left the courtroom quickly and quietly (in Northern’s defense, he argued another, emotionally charged case over school funding earlier that day). Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations Executive Director Rue Landau seemed thrilled by the proceeding. When asked how things went, Landau said “You can quote me on this” and hugged Feder.

This isn’t the same Supreme Court that overturned the Commonwealth Court’s first ruling for SEPTA in 2015. Since then, elections, retirements and scandals have replaced four of the seven justices. Justice Max Baer seemed convinced that a line in Pennsylvania’s own Human Relations Act, authorizing local governments to create their own commissions with “similar powers” as the state commission, evinced enough explicit legislative intent to settle the matter decidedly in the City’s favor. Rookie Justice David Wecht’s questions attempted to parse out how much ruling for one party might impede the other’s goals. The other justices barely spoke, if at all. Chief Justice Saylor, whose dissent last year strongly sided with SEPTA, seemed eager to get through the day’s 6th and final set of oral arguments. It’s difficult to make any predictions.

“I don’t like to read the tea leaves,” said Feder, “but I wasn’t convinced by my opponent’s argument. Were you?”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.