Remaking Sharswood: Rise and fall of the Norman Blumberg Apartments

It’s 6:30 a.m. on Saturday – chilly and still dark out.

Philadelphia Housing Authority CEO, Kelvin Jeremiah tries to warm up the crowd of people gathering under a white tent, clutching cups of coffee.

“Change has come to Sharswood-Blumberg,” Jeremiah said. “Doesn’t this feel great?”

Jeremiah is the chief architect of PHA’s large-scale plan to redevelop this neighborhood of North Philadelphia known as Sharswood. The agency has already begun acquiring roughly 1,300 properties in the area. The next step is demolishing the aging Norman Blumberg Apartments, PHA’s “most distressed” public housing complex.

There’s a story Jeremiah often tells about Blumberg. When he first took over the agency three years ago, he visited the complex twice without wearing his suit and tie. The second time, it was a Saturday night and Jeremiah claims he was confronted by a group of “entrepreneurs” – he won’t say they were drug dealers – and one of them, told him if he didn’t leave, he would be shot.

“I left Blumberg frankly feeling scared for my life,” he told PlanPhilly in a recent interview.

Now, there’s less than one hour to go before Jeremiah and others will push a large detonator and reduce all but one of the towers to a pile of rubble. Only the senior tower, which will be rehabbed, will remain.

Outside the white tent, people from the neighborhood are starting to congregate on Ingersoll Street, about six blocks away from the Norman Blumberg Apartments.

Mimi Riley’s family moved into a house nearby in 1972 and she’s feeling nostalgic.

“They getting rid of a lot of people,” said Riley.

Riley sees one of her neighbors, who won’t give us her name. Riley asks her if she’s sad to see Blumberg go. The woman shakes her head.

“No I’m not,” she says. “Because they shouldn’t have never built them before anyway. You don’t put people on top of each other like that.”

Riley’s surprised at her neighbor’s reaction.

“Wow, I always called them the ‘Good Times’ projects,” she says. “When I got out of school, came by, saw people going in there. Always wanted to go in there, but I could never go. I hate to see it go.”

I ask Riley if the people in Blumberg looked like they were having a good time.

“No, not at all,” she says with a belly laugh.

But there was something about the place, she adds. It’s where all the people were.

“Concentrated poverty”

When Blumberg was built in the late 1960s, it was at the tail end of a public high-rise building boom in Philadelphia. Federal housing officials at the time said it was the best way to house the largest number of people for the least amount of money. It was also a way to clear blighted blocks in the inner city – “slum clearance,” they called it.

The Blumberg complex took up eight acres of the North Philly neighborhood known as Sharswood and consisted of two brick high-rises, a senior tower and 15 low-rise buildings, all clustered around a courtyard.

By the late 1960s, when the first families were moving into Blumberg, public housing had already gotten bad reputation in America and the story of Blumberg is the story of many high-rises across the country.

“Those towers became homes of just concentrated poverty,” said Mark Joseph, a professor at Case Western Reserve University who studies public housing.

Many of these projects were being built in poor, mostly black neighborhoods like Sharswood, where middle-class families were moving out and there were few opportunities for work.

“What comes along with concentrated poverty are a host of other social ills – disinvestment in not only the housing, but the schools, other community amenities… which then leads to other problems like crime, violence,” Joseph said.

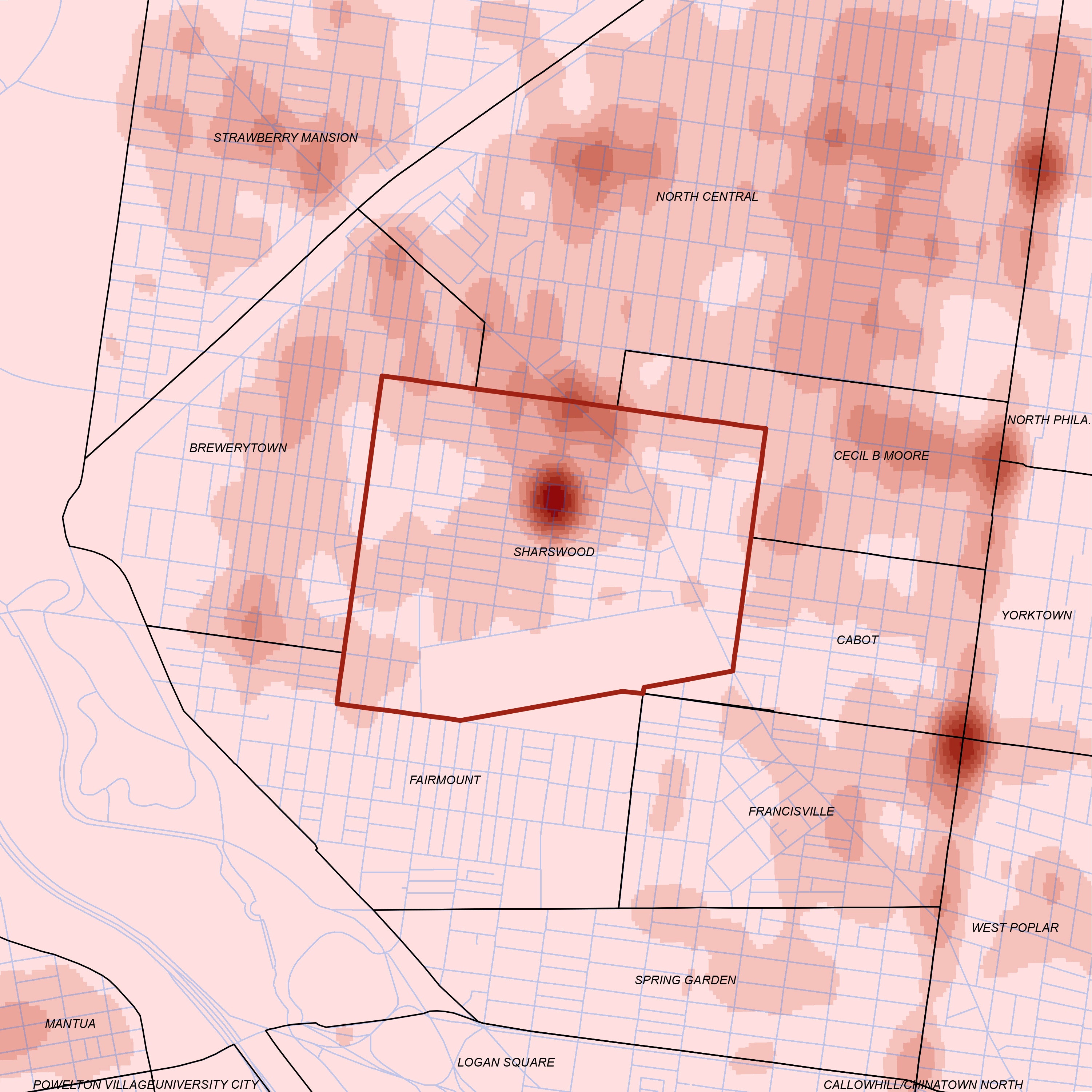

By the time more than 500 families were forced to move out last summer in preparation for Saturday’s demolition, the poverty and crime rates at Blumberg were double the rest of the city’s. Crime maps show Blumberg like a bright red dot in the middle of Sharswood, a clearly marked hot spot for violent and drug crimes.

Outside the Blumberg complex, the rest of Sharswood is pocked with vacant lots and boarded-up, dilapidated homes while surrounding neighborhoods, such as Fairmount and Brewerytown, have been gentrifying rapidly with new housing and restaurants.

Conditions inside the Blumberg buildings deteriorated as well, as fluctuating federal dollars and an ever-growing demand for more affordable housing stretched thin resources for agencies like the Philadelphia Housing Authority.

“The towers actually started falling, like the bricks was coming off,” said Shakera Zellars, who lived in the low-rises for 12 years. “And I don’t think they was doing a good job as far as keeping them up, as far as cleaning them.”

Zellars and other former residents spoke of stairwells that reeked of urine and dirty diapers, constantly breaking appliances and elevators, and the frequent sounds of gunshots.

Many also described a feeling of always needing to watch their backs, or if they were children, parents who were hyper-vigilant about their safety.

Lisa Moore, who lived in the senior tower for five years, compared it to driving a car.

“You gotta drive for the person in front of you and the person behind you… to keep from having an accident and that’s how it is in Blumberg,” Moore said. “Sometimes you got to be mindful because everybody don’t think like you… You wake up in the morning and you find out, six people got shot on the same corner that you crossed going home.”

A close community

At about 6:45 a.m., the sun is just starting to come up over the Blumberg towers. As more people gather in the street, the vibe starts to feel like a family reunion.

Lorenzo Higgins puts his arm around a friend. He’s wearing a black t-shirt with the words “Straight Outta Blumberg” written in white fabric paint, which he had made just for the occasion.

Higgins’ family moved in when the towers were first built and life there was “different” then, he says. He remembers the other parents who helped raise him and playing on the Blumberg basketball team.

“It was really close,” he says. “It made you feel like you was part of something and for me, it gave me a lot of growing experiences really in the way of coming up.”

For the last eight years, Higgins says hundreds of people have shown up for an annual Blumberg reunion in Fairmount Park.

He moved out several years ago, but his mother lived there for more than 47 years, until she was forced to leave last summer.

“We had to damn near drag my Mom out of there,” he says with a laugh. “I’m just hoping what they’re getting ready to do is going to be something bigger and better.”

The future of Sharswood-Blumberg

Bigger and better is exactly what the Philadelphia Housing Authority is promising.

Over the next 10 years, PHA wants to transform Sharswood from a neighborhood wracked by poverty and blight into a “mixed-income community.”

The half-billion dollar plan involves building more than 1,200 new units of affordable and market-rate housing and revitalizing the commercial corridor on Ridge Avenue, including a new supermarket. There is also conversation about reopening one of the neighborhood’s two shuttered public schools.

Case Western’s Mark Joseph has studied mixed-income developments in Chicago, San Francisco and other cities, and his research could reveal what’s in store for Sharswood-Blumberg.

“The big success is the physical transformation,” he said. “Places that were no-go zones in many of our cities and you go back there today, you literally cannot believe where you are.”

The downside, Joseph has found, is that only 15 to 20 percent of former residents tend to come back and experience the higher quality of life of these new developments. Another challenge is building community among people of varying incomes.

“Unfortunately, what we’ve seen in much of our research is that over time… you have some friction, some tensions that emerge,” Joseph said.

The success of this large-scale, multi-phase project could also hinge on the results of this year’s presidential election.

The Sharswood-Blumberg Transformation Plan, as PHA calls it, was designed with the help of a $500,000 planning grant from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development under President Obama’s Choice Neighborhoods program. HUD has given out 63 Choice Neighborhoods Planning Grants. However, it has only given out 18 of the $30 million Choice Neighborhoods Implementation Grants. The federal government has not announced when it will open another round of implementation grant applications. Joseph said it’s unclear whether all cities that received planning grants will receive money for implementation. He also wonders how the federal government could change its approach to affordable housing under a new president.

However, Joseph does not predict that the half-billion dollar Sharswood-Blumberg Transformation Plan would collapse without a $30 million implementation grant from HUD.

“It means it’s going to happen far more slowly,” he said.

“A lot of memories”

Many former residents like Higgins are optimistic. The change was “a long time coming,” they say.

Still, as the towers fall just before 7:30 a.m., it’s difficult to watch.

After two loud explosions, Higgins has to stand still and compose himself.

“A lot of memories,” he says, shaking his head.

But there’s no time to rest in the moment – an enormous dust cloud is rolling over the streets, scattering the crowd. Higgins hopes his family and friends will be able to come back after it settles.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.