Political sex scandals and the culture of confession

Listen

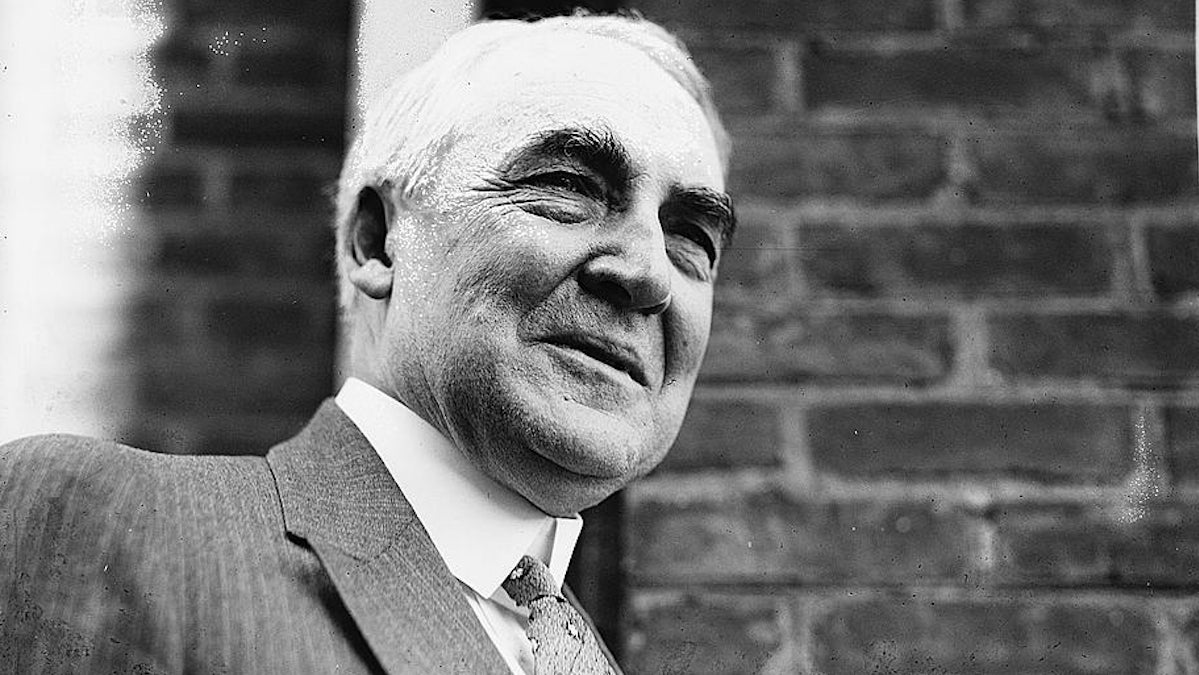

Republican Warren G. Harding was the 29th President of the United States (1921-1923).

So it turns out that Warren G. Harding really did father a love child with one of his mistresses, Nan Britton. Last month, descendants of Harding and Britton confirmed that DNA evidence linked their families to each other.

But Harding never discussed the matter in public, which separates his time from ours.

Today’s sexually wayward leaders are required to grovel, confessing their sins to the world. Think Bill Clinton and John Edwards, Mark Sanford and Anthony Weiner.

That makes us feel superior to our politicians, but—in the end—it diminishes our politics. It’s easy to mock our Victorian forbears, with their formal manners and blind spots on race and gender. But they kept silent about their personal transgressions, even in the face of salacious reporting about them. And we could all stand to learn from that.

Consider the first sex scandal in presidential politics, involving Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings. A frustrated officeseeker published a series of articles in 1802 exposing Jefferson’s relationship with Hemings, a slave who bore him several children. Other enemies of the president tried to capitalize on the reports, even publishing a cartoon that showed Jefferson as a rooster and Hemings as a hen.

Like Harding’s dalliance with Nan Britton, the Jefferson-Hemings affair has since been confirmed by DNA testing. But it didn’t have any political repercussions at the time for Jefferson, who was re-elected in a landslide in 1804. Many Americans didn’t think Jefferson’s behavior was particularly wrong, so long as he kept it discreet.

And that’s exactly what he did. So far as we know, Jefferson never acknowledged the matter in public. And he certainly didn’t reply to his opponents’ attacks, which would have kept them in the news for even longer.

Ditto for Grover Cleveland, who faced accusations during his 1884 White House bid that he had fathered a child out of wedlock. Newspapers printed long and steamy reports about Cleveland, who was mocked on the campaign trail by Republican crowds that chanted, “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa”? (After Cleveland won, Democrats would retort, “He’s gone to the White House, ha ha ha.”)

The love-child charge was true, but Cleveland never made public mention of it. “The policy of not cringing was not only necessary but the only possible way,” he later reflected. Cleveland did allow his aides to discreetly inform newspapers that he was paying to support his child. He also let it be known that he had confided in a minister: confession was still a private act, not a public one.

So it remained into the early 20th century, when Warren Harding made his name as a so-called “ladies’ man.” Apparently, women found Harding irresistable. And he didn’t make any effort to hide that; instead, it contributed to his somewhat rakish appeal.

“It’s a good thing I’m not a woman,” he joked to a private party of reporters at the National Press Club. “I would always be pregnant. I can’t say no.”

But when Harding was charged with fathering a child by Britton, he stonewalled. Like Cleveland, he privately paid to support the child. The matter didn’t become truly public until after his death, when Britton tried to get Harding’s heirs to give her part of his estate.

When they balked, she wrote one of the first big kiss-and-tell books in American history. Bearing the provocative title of The President’s Daughter, Britton’s book sold over 90,000 copies. But it was also banned as obscene by censors around the country, who especially objected to a passage about Britton and Harding having sex in an Oval Office closet.

Today, American airwaves are crowded with titillating stories about the sexual lives of politicians. But our fallen leaders feel duty-bound to admit–and, especially, to apologize for–their sinful ways. That might reflect the postwar rise of televangelism, which brought public confession into America’s living rooms. It also echoes the pseudo-therapy of afternoon talk-shows, where all the guests are supposed to bare their souls to the rest of us.

Nobody understood that better than William Jefferson Clinton, who went on national TV in 1998 to tell the world about his affair with a young White House intern named Monica Lewinsky. “I did have a relationship with Miss Lewinsky that was not appropriate,” Bill Clinton said. “I misled people, including even my wife. I deeply regret that.”

Cut to John Edwards and his videographer, Mark Sanford and his “soulmate,” Anthony Weiner and his . . . well, you don’t want to know. But here’s what our leaders want you to know: they’re sorry. Very sorry.

I’ll take the stoic Victorians over this soap opera, any day. Once upon a time, American politicians understood that confessing their darkest secrets would degrade all of us. The next time you see another public figure begging for forgiveness about a purely private matter, ask yourself whether it’s any of your business. You might be sorry about the answer.

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches history and education at New York University. He is the author of Too Hot to Handle: A Global History of Sex Education, which was published in March by Princeton University Press.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.