Pittsburgh’s modernist past has lessons for today’s urban renewal

Listen

Rami el Samahy, who helped put together the Imagining the Modern exhibit at the Carnegie Museum of Art, with some of the show's archival photos. (Irina Zhorov/WESA)

An exhibit of Pittsburgh’s urban planning past comes at a time when the city is actively planning for the city’s future, and has lessons to offer.

Modern urban planning sought ways to make life easier. Often, it involved wholesale demolition of large swaths of a city in the service of big “renewal” projects. In many cases the planning didn’t include public input, and the projects were one-use, whether retail, business, or culture.

When modernism came to Pittsburgh, the city really ran with it. The Alcoa Building and U.S. Steel Tower both went up during that time, reshaping the city’s skyline with novel materials (aluminum panels and exposed steel beams, respectively). A Civic Arena built during the time looked like a sleek spaceship — one with a retractable roof — landed in the city.

“I joke that this was sort of Pittsburgh’s Dubai moment,” said Rami el Samahy, an architect with the company over,under and an assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University, in Pittsburgh. He helped put together a new exhibit at the Carnegie Museum of Art examining the Pittsburgh Renaissance, which was the city’s iteration of the modernist movement, lasting from the late 1940s into the 1970s.

Called “HACLab Pittsburgh: Imagining the Modern,” the show consists primarily of mixed-media archival materials and focuses on several specific projects: redevelopment of the Lower Hill, Oakland, Allegheny Center, Gateway Center.

The exploration of Pittsburgh’s urban planning past comes at a time when the city is actively planning for the city’s future, and has lessons to offer.

An example to others, even with problems at home

The Renaissance was a response to a very specific set of challenges identified by civic and business leaders in the city: terrible air quality, blight, traffic congestion, inadequate housing. At the time, Pittsburgh was booming and its population about double today’s. A new mayor with a vision of how to address those problems, and a willing business community, made the Renaissance possible.

The above images, part of the Imagining the Modern exhibit, were in a pamphlet put together by the Allegheny Conference. The brochure presented the problems Pittsburgh was experiencing at the time and solutions to them. (Credit: Allegheny Conference and over,under)

“The downtown redevelopment effort was really one of the first in the country,” said el Samahy. “And it was considered such a success story that it was used as a model for subsequent urban renewal.” While some cities cited specific Pittsburgh projects in their own redevelopment plans, much of what Pittsburgh’s efforts inspired was the audacity to think big.

But not all of the projects were completed as planned and some of them have since been demolished. Much of the Renaissance work has fallen out of favor. Still, el Samahy said “a lot of thought went into [it],” even if “in hindsight we might think it was the wrong kind of thought.”

Take, for example, the urban highway network designed to reduce congestion. While it helped ease traffic problems, it also blocked off waterfronts, isolated certain neighborhoods, and made the city car-reliant. The Civic Arena, then seen as a cultural acropolis, displaced thousands of African American residents from the Lower Hill. The Allegheny Center Mall, which was built to fight suburban flight and compete with suburban shopping centers, is today a strangely quiet office complex surrounded by a wide boulevard that quarantines it from the rest of the neighborhood.

El Samahy, despite these problems with Pittsburgh’s modernist projects, takes the role of advocate for what projects remain. Rather than remove everything again and start over — which is what many of the modern plans did — maybe it’s just time to rethink what’s there, he said.

Re-thinking, not razing

The archive materials in the exhibit help contextualize Pittsburgh’s Renaissance with what was happening in the city at the time, as well as how other cities were approaching redevelopment.

A more forward-looking component is the active studio that is also part of “Imagining the Modern.” An architecture class from Carnegie Mellon University, taught by el Samahy, meets in one of the galleries. The students will spend the semester rethinking the Allegheny Center.

On a recent afternoon, the sound of hammering echoed through the exhibit halls as students put up their first assignment. They had to create mini-exhibits that presented the Allegheny Center as an experience rather than a physical space.

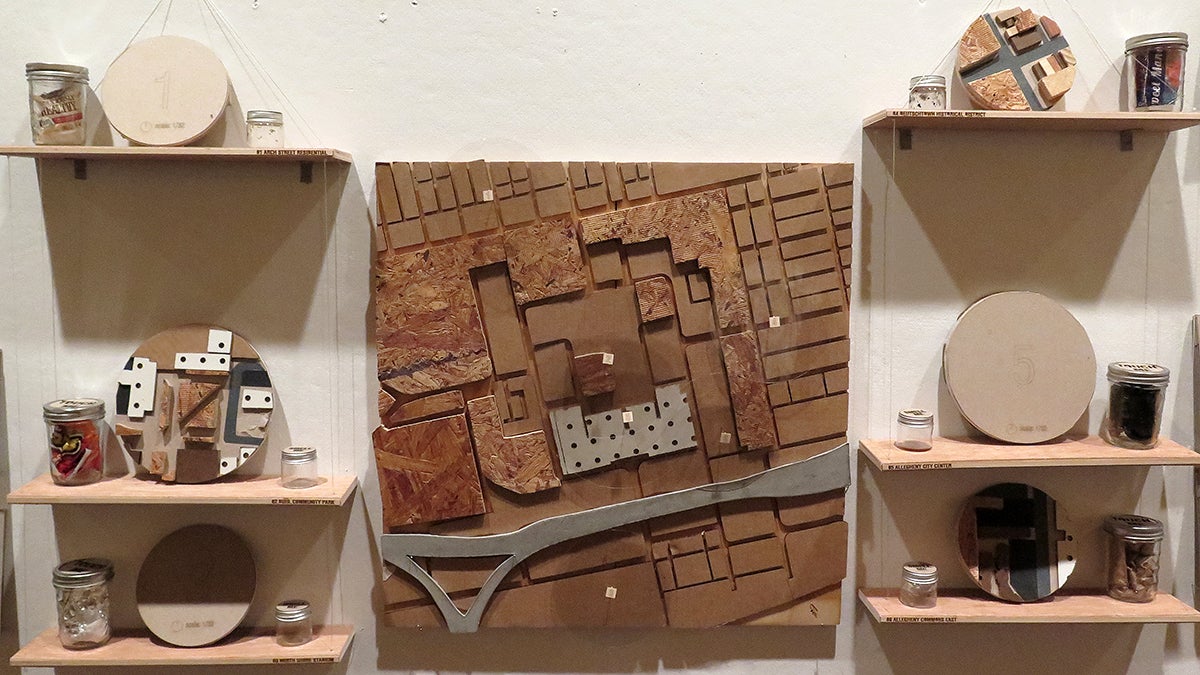

One of the student groups’ mini-exhibits. This group captured the experience of the Allegheny Center by presenting things like the textures and smells they encountered when they visited the site. (Irina Zhorov/WESA)

One group collected audio from their walk and played it out of neatly assembled boxes. Another collected smells — the smell of cookies for an area where children play, stale cigarettes from a smoking area — and had little jars in their display. Yet another built topographic maps to represent concentrations of things like transportation availability and noise pollution.

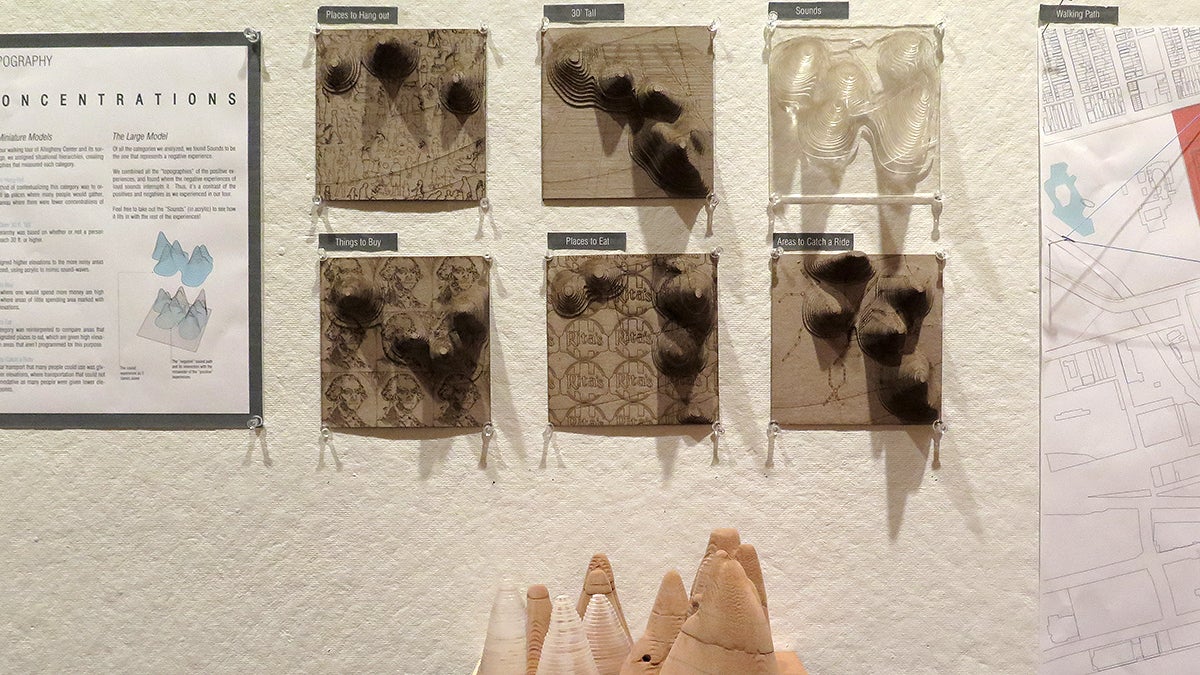

This group represented the Allegheny Center and its surrounding by making topographic sculptures, where the peaks signaled concentrations of something. They evaluated concentrations of places to hang out, of buildings over 30 feet tall, sounds, things to buy, places to eat, and areas to catch a ride. (Irina Zhorov/WESA)

During the critique, Clara Lee, a student, marveled at the Allegheny Center. “It’s abandoned, it’s almost like a dystopian unit. It’s an existing relic of modernism. A lot of people who oppose modernism, this is the reason why,” Lee said. “I’m so excited.”

El Samahy says when he chose the Allegheny Center for his class nothing was happening with it. But soon a developer announced plans to revamp it into a technology and innovation center.

Now, the rethinking isn’t just theoretical.

In fact, it’s happening all over Pittsburgh. A major firm will be looking at the Lower Hill site, another Renaissance relic. There are ambitious plans for a defunct steel mill site on the Monongahela River.

Unlike many U.S. cities, Pittsburgh is thinking big again. El Samahy said Pittsburgh once again has a mayor with a vision, a strong foundation community, and many important businesses still remain — a perfect storm. And just like before, that could ultimately be good or bad.

“I was talking to an architect the other day and we were shaking our heads saying ‘what were they thinking?’ And I said ‘I wonder how long from now people will be saying the same thing about us?’” el Samahy said, laughing.

He said there are many lessons today’s project planners can learn looking at the modernists, and one of them is humility.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.