Philly Free Streets organizers report back on last year’s event, prepare for another

The organizers of last September’s Philly Free Streets – a half-day event which shut down automobile traffic to create a pedestrian and bicycle path stretching from the eastern end of South Street to the Schuylkill River Trail, along Martin Luther King Drive and into West Fairmount Park – released a report highlighting the event’s successes and shortcomings in advance of organizing a second one sometime this year.

At an event Thursday, marking the report’s release, representatives from PennPraxis*, the nonprofit research arm of PennDesign that authored the report, joined Open Streets PHL, which advocated for the event, and the city’s Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems (OTIS) to discuss lessons learned. Free Streets was Philadelphia’s first official open streets event, a worldwide movement aimed at getting city residents to imagine and use streets for people rather than just cars. The idea took off in Philly after the Pope’s visit in 2015 closed large sections of Center City to cars, resulting in a de facto open streets event.

“This is more than about closing some streets,” said Patrick Morgan, Philadelphia program director for the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, which funded the report. “It’s about changing how we live, it’s about changing our expectations, it’s about changing how we connect to each other, and it’s about changing how decisions are made in this city.”

An estimated 30,000 people walked, jogged, or biked on the drizzly Saturday morning over the five-hour event last September.

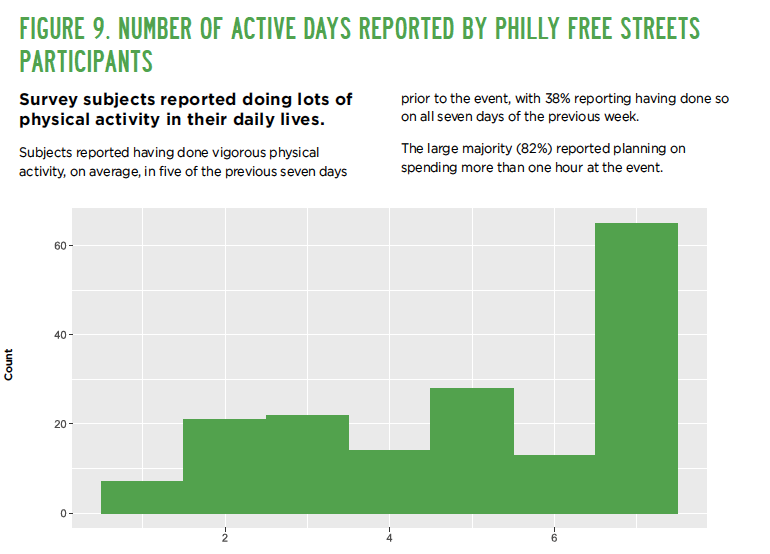

The report sets the stage for a pivot of purpose: billed the first year as a public health initiative of the get off the couch, get up and move variety, the study shows most participants were already active. In the previous week, participants surveyed said they worked out five days on average; the mode was seven.

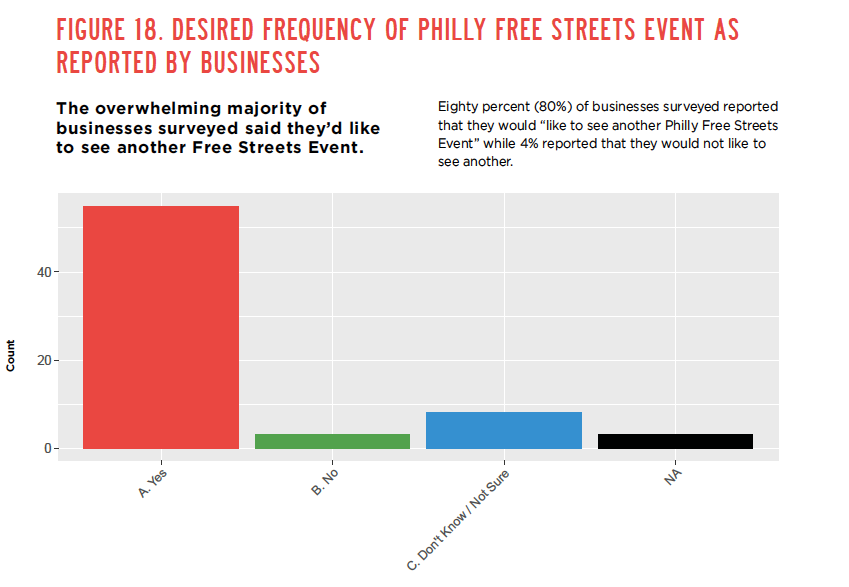

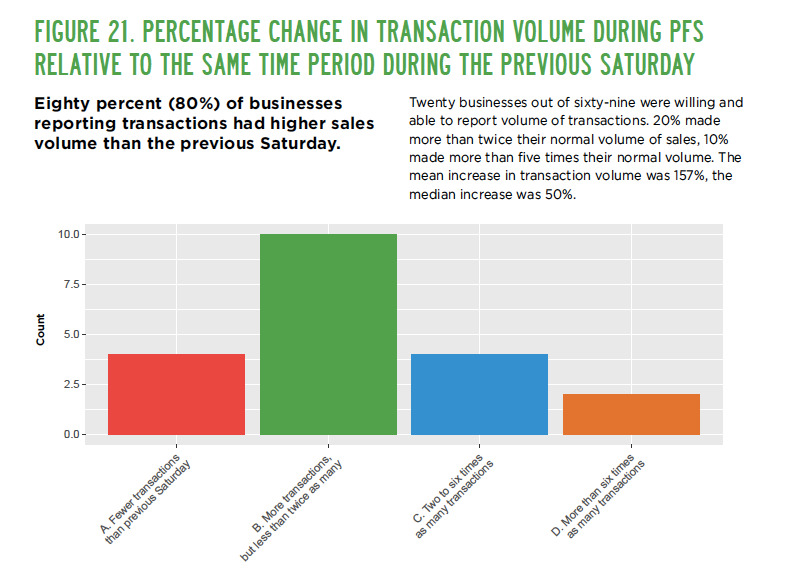

But if Free Streets didn’t encourage participants to burn more calories, it did inspire them to burn more cash: 80 percent of surveyed businesses along the route said business volume was up compared to the previous Saturday. Perhaps uncoincidentally, 80 percent of businesses said they’d want to see another free streets event.

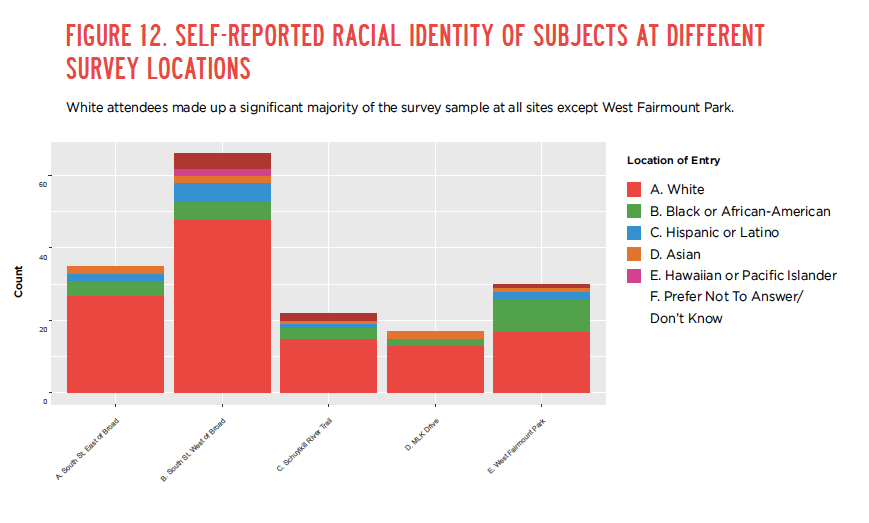

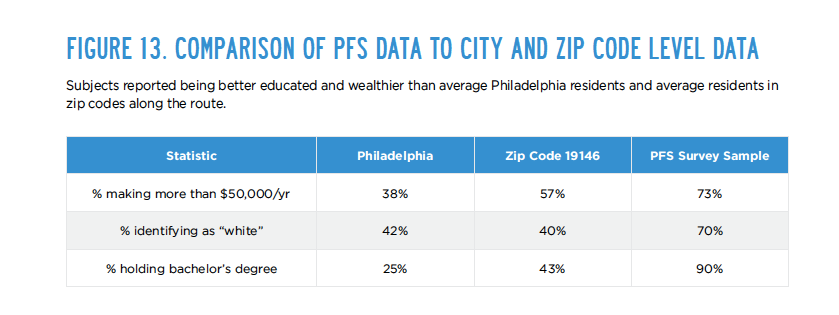

The first Free Streets organizers also hoped to attract a diverse crowd, but fell short of that goal. The report, based on a survey of 170 participants plus 69 of the 112 businesses located along South Street, found that 70 percent identified as white, 90 percent held at least a bachelor’s degree, 73 percent earned more than $50,000 a year, and just over half were between the ages of 18 and 34.

Most of the route traveled through relatively white and affluent parts of town, except for West Fairmount Park. There, the number of African-American participants increased, suggesting that a route through more diverse neighborhoods could significantly influence the crowd’s makeup. Fifty-four percent of survey subjects said they lived in zip codes within a quarter mile of the route. OTIS officials were coy about where the next Free Streets would be held, as that’s still being negotiated.

During the panel discussion, Mike Carroll, the deputy managing director for OTIS, said the city was committed to holding another free streets event “before 2018.” Carroll said the first Free Streets cost the city around $125,000. Finding funds will be important for future iterations of Philly free streets — unlike street festivals, which pack blocks with revenue-generating beer tents and food trucks, open streets events lack a built-in money making strategy.

Charlotte Castle, a project manager at OTIS, said one of the goals of the next Free Streets event would be in “making this really a transportation program… so that people can really begin to imagine their streets not just for people driving but also for people walking through neighborhood and people biking and having families on bikes.” To that end, Castle said they were looking at ways to separate faster moving bikes from the more leisurely walkers.

Castle later agreed with a crowd suggestion that the next event offers a unique opportunity to pilot different types of sometimes-controversial bike/pedestrian infrastructure, like protected bike lanes. Of course, given the young, active, urbanist demographic that participated in the first, which could amount to preaching to the choir.

The survey’s results offer an incomplete snapshot. First, it skewed towards pedestrians over bicyclists, who were harder to get to stop for the survey. More importantly, there’s an inherent selection bias at play, surveying only those who participated, a group who at least thought they’d enjoy the event (or else they would have just stayed away).

* NOTE: PlanPhilly founded as a project of PennPraxis, where it remained until March 2015 when PlanPhilly became part of WHYY.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.