Pennsylvania’s sexual abuse laws leave survivors conflicted

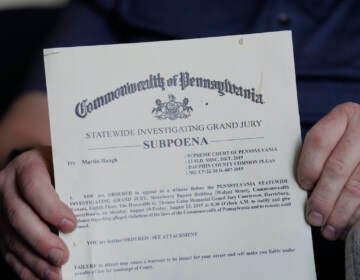

When Pennsylvania overhauled its child sexual abuse laws after a years-long battle, absent from the bill-signing ceremony were some of the people who had worked hard.

Victim advocate Jennifer Storm, second left, joins survivors of child sexual abuse including Patty Fortney-Julius, third left, and Mary McHale, second right, waiting for a news conference in the Pennsylvania Capitol, in Harrisburg, Pa. (Marc Levy/AP Photo)

When Pennsylvania overhauled its child sexual abuse laws this week after a years-long battle, absent from the bill-signing ceremony were some of the people who had worked hardest for the changes.

Some sexual-abuse survivors and victim advocates felt conflicted by the compromise package: Missing was a cornerstone of the recommendations by last year’s landmark grand jury report on child sexual abuse inside six of Pennsylvania’s eight Roman Catholic dioceses.

That recommendation was for a two-year window in state law to allow now-adult victims of child sexual abuse to sue over claims that are past Pennsylvania’s statute of limitations.

Republicans who control Pennsylvania’s Senate, in a party-line vote, defeated it, 28-20, after longtime opposition by bishops and insurers. As an alternative, they offered the longer, more deliberative process of amending the state constitution to create a two-year window to sue.

That has left survivors and victim advocates knowing they have little choice but to trust lawmakers to pass a resolution to amend the constitution in the 2021-22 legislative session. Then they may have to fend off a legal challenge or a well-funded campaign to defeat it in a statewide voter referendum.

“We had hope up until the end,” said Mary McHale, a Reading resident who told the grand jury of her experience 30 years ago as a 17-year-old in a Catholic high school. “And we’re not done. We’re not finished, this is just a different route. But it’s hard when something’s right there and it’s tangible, and you have hope and then it’s gone again.”

Among the provisions signed into law is one giving future victims of child sexual abuse until their 55th birthday to sue their perpetrators and institutions that may have covered it up.

Many adults in Pennsylvania who were sexually abused as children lost their right to sue when they turned 20, and they say they are powerless to go to court, where a judge can force an institution to divulge what it knew.

“When you talk to victims, the absolute biggest thing is discovery, holding perpetrators accountable to get them off the street, holding institutions accountable so things change,” said Patty Fortney-Julius, one of five sisters from the Harrisburg area who have accused their now-dead parish priest of sexually abusing them as children.

Lawmakers, they say, could vote both to change the law and the constitution.

“They presented this constitutional amendment as their way of ensuring our justice,” said Brooke Rush, who has told of being molested at age 11 by Johnstown pediatrician, Johnnie Barto, who prosecutors say spent decades abusing patients in his exam room. Barto was handed effectively a life sentence in March. “So, if they truly wanted the end result of the retroactive window, there’s no reason they shouldn’t have let both go forward together.”

While the Senate was holding up the legislation this year, Pennsylvania’s dioceses opened temporary victim compensation funds. Many people who applied took the offer of money. But it came with strings attached: They had to agree not to sue.

Rush and others are now questioning whether lawmakers are committed to seeing through a constitutional amendment. They also worry about lawsuits to block it or how it might be fought in a statewide referendum.

“There are a lot of people with the money and interest to see that this thing never comes to light,” said Jennifer Storm, who directs the state’s Office of Victim Advocate.

Storm worries about a TV ad campaign, warning voters that passing the referendum will jack up their taxes.

Rep. Mark Rozzi, D-Berks, predicted that a referendum will pass easily because voters who have read about sexual abuse scandals understand the need to deliver justice to victims.

“If we would put it on the ballot box tomorrow, I think it would pass with 90% voter approval,” he said.

Rozzi, a longtime sponsor of the legislation who has spoken publicly about his rape as a 13-year-old by a Roman Catholic priest, shifted his stance earlier this year to support a constitutional amendment after years unsuccessfully pushing for a two-year window in the law.

It was, he said, a necessary compromise in the face of Senate Republican opposition and the potential that a court challenge would block it. His change in stance caused a rift among victim advocates, including some who skipped Tuesday’s signing ceremony.

But, Rozzi said, “they will understand when we get to 2021 why we did the things that we did.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.