New Philly exhibit celebrates lives, contributions of scientists with disabilities

A new exhibit at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia tells the stories of scientists with disabilities — and shows how they overcame prejudice and marginalization.

An exhibit at the Science History Institute highlights the accomplishments of scientists with disabilities. The chemist John Dalton, pictured below, noticed his inability to distinguish between red and green and created a color blindness test. (Steph Yin/WHYY)

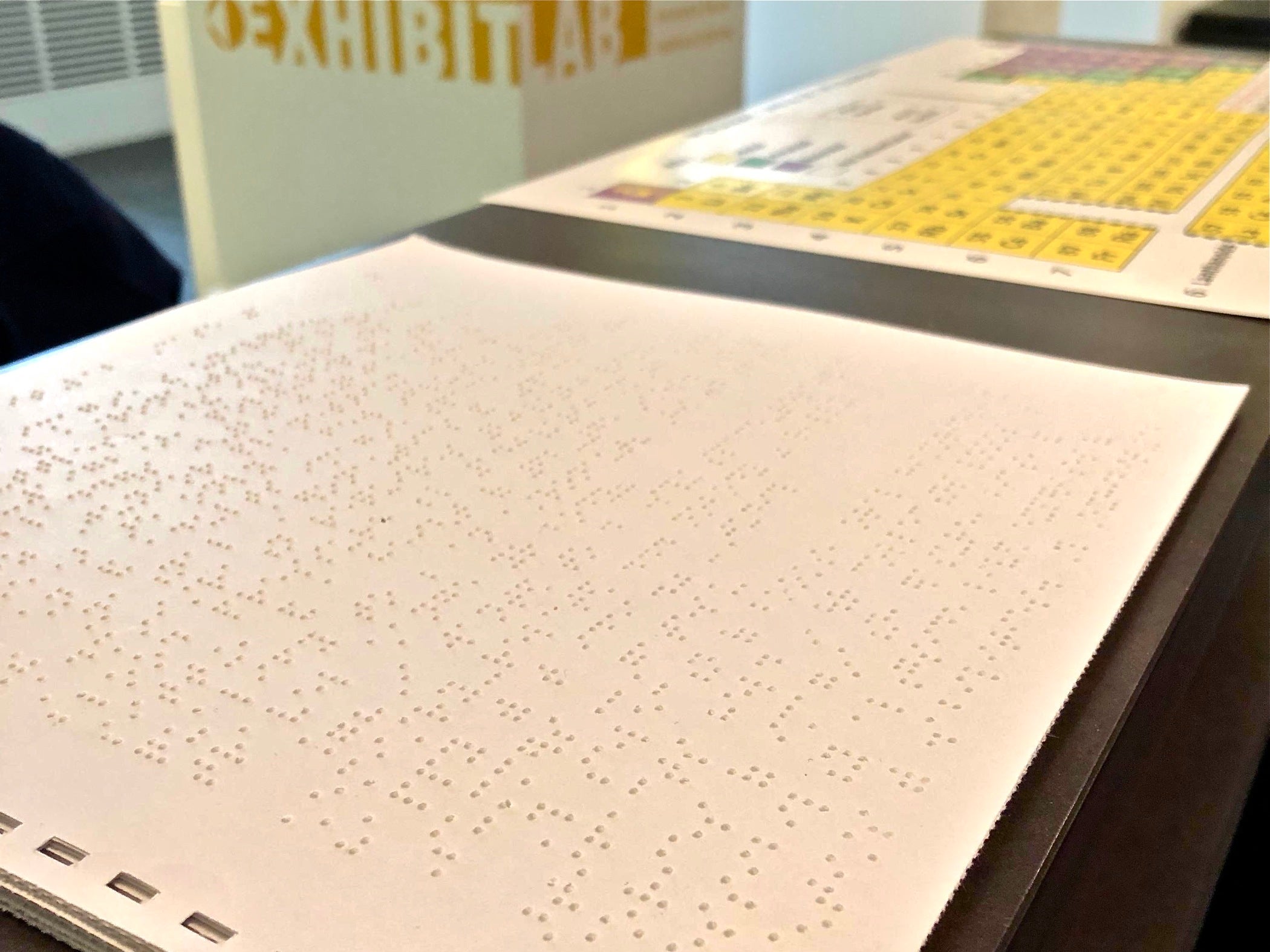

Enter the Science History Institute, in Philadelphia’s Old City, and you’re greeted by a stack of papers patterned with Braille. They’re pamphlets for the museum’s new exhibit, which explores science and disability.

It’s a change for a museum that often displays old scientific paraphernalia not available for touching.

“The museum as a whole has been really trying to think about issues of access,” said Jessica Martucci, a research fellow. “And so with this exhibit we really wanted to think about, ‘How can we introduce more tactile aspects into the stuff that we’re doing?’”

The exhibit is part of an ongoing project, in which researchers at the museum have been collecting oral histories from scientists with disabilities. Too often, these stories have been neglected, or rendered invisible, said Martucci, who co-leads the project.

In one display case, a periodic table is missing 22 elements — including oxygen, helium, calcium and sodium. These elements were all discovered by scientists with disabilities.

The table shows that people who are differently abled have always been part of science and knowledge, Martucci said.

“The fact that we don’t necessarily know that is not a reflection of reality,” she said. “It’s a reflection of historical choices about who gets included in these stories.”

Not only is this history incomplete, Martucci said, but it makes science less welcoming to people who don’t see themselves reflected in it.

That hurts science as a whole, she said, because it limits the questions posed and the methods used to make discoveries.

“Even just thinking in the most obvious terms, a blind scientist is going to learn very differently from someone who can rely on their sight,” she said. “Especially when you’re talking about studying things that you actually can’t see with your naked eye — why are we relying only on visual models to understand these things?”

Another display explores how prejudices such as sexism and ableism can compound one another, making it difficult for people with intersecting marginalized identities to navigate science.

In a recorded interview, Judith Summers-Gates, a chemist with low vision, discusses the challenges she has faced as she’s fought since the 1970s to make science more inclusive for both women and people with disabilities.

Systems are set up to close off opportunity to people like Summers-Gates, Martucci said.

One mainstream narrative that is particularly harmful, she added, is that it’s the responsibility of people with disabilities to overcome any obstacles in their way.

Instead, communities should step up and find ways to support people with disabilities, she said.

That can include low-cost, simple changes. One blind chemist told Martucci that he got through his undergraduate chemistry classes by working with an art student, who created raised-line paintings of the diagrams in his organic-chemistry textbooks using puffy paints.

“It didn’t require the latest high-tech gadgetry to do that,” Martucci said. “It’s really more about a shift in mindset, and thinking creatively.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.