In the Gap: Neighborhood violence

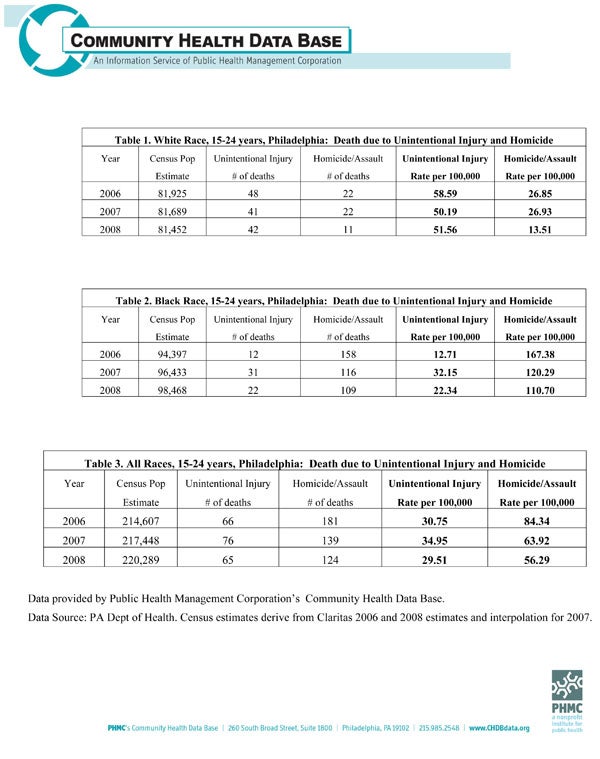

This month our series—In the Gap: Voices from the Health Divide—examines new ideas about protecting young people from violence. Accidents are the No. 1 killer of all people age 15 to 24 in the United States, but among young black Americans, assault is the leading cause of death.

Traditionally, helping young people avoid neighborhood violence has meant coaching them to steer clear of trouble.

“If you know that house or that street has a history of major drug activity, or violence. Then you can’t go by there. That’s just something that you teach them,” said Rudy Johnson, a social worker with the Philadelphia Anti-Drug Anti-Violence Network.

“If a situation does, as our young people say, kicks off. Where do you go or what do you do? You don’t need to be on that street,” Johnson said.

But what if your whole neighborhood feels like “that street?”

Dr John Rich

Dr John Rich

Drexel University scholar John Rich was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” Grant for his research into the ways violence and trauma effect health.

“We somehow have this idea that if we just change everyone’s individual behavior we could improve the health of the population. That’s not an effective way to go. If we can change the environments in which people live we will have a much greater impact upon the health of our community,” Rich said.

Rich says some neighborhoods offer fewer chances to find legal employment, go to college or even walk to school in peace.

“There’s a stress associated with having to think about which way you’re going to walk to school today so you don’t get beaten up,” Rich said. “And (it’s stressful) when you don’t have confidence that the police car that rolls up alongside of you whether they’re there to protect you or to frisk you,” Rich said.

In his book Wrong Place, Wrong Time: Trauma and Violence in the Lives of Young Black Men Rich tells stories of African Americans who have been assaulted. He said many of the clashes between victims and perpetrators were logical reactions to what each man saw around him.

“Given that they lived in a hostile environment, if they didn’t retaliate, then other people, seeing their failure to act would take advantage of them,” Rich said. So many young people feel that they were using violence as a strategy to prevent victimization.”

Rasheed Abbott was shot in his West Philadelphia neighborhood.

“Everybody from West (Philly) knows what 52nd Street is. It’s the center of everything. You want anything, go to 52nd Street. Whether bad or good,” he said.

On the day of his shooting, another man approached Abbott talking loudly. Abbott says the man was “testing him.”

“Then it became, I guess, an altercation. I’m like, ‘Whoa, you just threatened me. You can’t walk away now. So when I tried to walk toward the person, the person turned around and started shooting,” Abbott said.

At age 25, Abbott was a drug dealer living in way—and in an area—with lots of risk for violence.

“I went to Huey (Elementary School). I want to say it’s a good school. It was just in the middle of not-so-good things. Soon as you got out of school, the whole park was lined up with everybody doing stuff they weren’t supposed to be doing, and you knew half the people over there anyway—friends, uncles, neighbors,” Abbott said.

Abbott says he did the short term math, and started selling drugs and carrying a gun.

New efforts to curb violence work on the idea that risk is not only based on the things you personally do.

“You can not keep a white T-shirt on in a trash can and think it’s going to stay clean. OK, I’m not going to touch this, I’m not going to do this. You’re surrounded by it,” Abbott said.

Nearly a decade later, at age 34, Abbott still lives in West Philadelphia, but says he has changed his environment.

“The first thing that happened was I had a son. I had to take a step back, evaluate my situation and do something different,” he said. “I have to make sure that my kids can walk up and down the street if they choose to.”

A pilot program in California is trying to multiply that kind of individual change across entire communities. The California Endowment, lead by former Philadelphia Health Commissioner Robert Ross, will spend a billion dollars in 14 communities over the next 10 years.

Tony Iton is the foundation’s vice president.

“It’s not really all that different from kids in Palestine,” Iton said. “When we constrain kids’ opportunities, they know it, they feel it. They get angry and frustrated and they act out. And, they act out frequently in ways that are violent.”

Planners are looking for ways to improve high school graduation rates and change policies that push troubled students out of class too soon. The endowment will work to give bike lanes and green space to cities that don’t have them.

“We have our own money to help illustrate that health really happens in neighborhoods, and prevention is really about creating conditions that afford people the greatest opportunities to make healthy choices,” Iton said.

At a time when many cities are reeling from budget cuts, Iton says his foundation has the resources and patience to invest in long term solutions, to move resources into disadvantaged neighborhoods and better mobilize the strengths already there.

The In the Gap audio series is a partnership with 900 AM WURD. Taunya English will discuss this story on WURD’s HealthQuest Live show on Monday June 27 at noon.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.