In North Philly, neighbors and the Philadelphia City Planning Commission look to the future

On Monday night, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission held its final public meeting about the North District, which covers many of the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

The open house offered a glimpse of the Commission’s proposals for the North District, after months of community feedback online and in-person.

The commission highlighted three focus areas for the district moving forward. These include the dilapidated North Philadelphia train station, which is currently hemmed in by weedy surface parking lots and vacant industrial buildings. The station is being eyed by out-of-town developers, who see it as a potentially lucrative site due to its access to Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor line, allowing for rapid access to New York and Washington, D.C.

“We are focused on ensuring the public good no matter what happens in the future,” said Ashley Richards, the lead planner in charge of the North District planning process. “Right now, it’s desolate. We want to restore the station, connecting access to Broad Street Line, SEPTA’s Regional Rail, and Amtrak.”

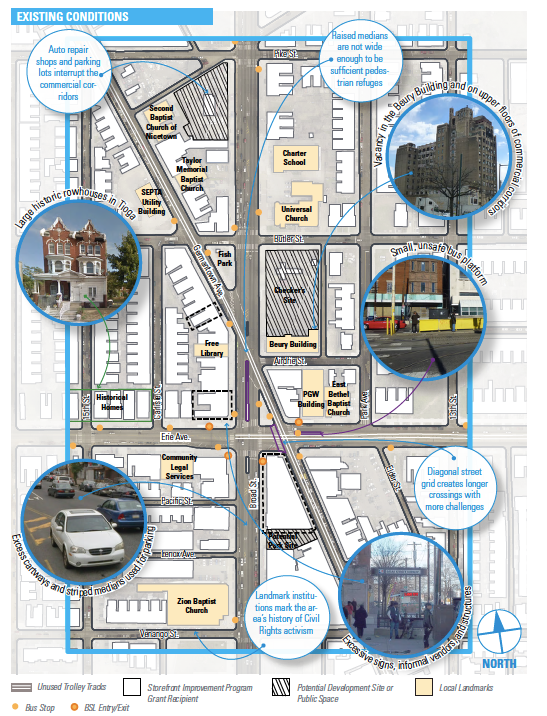

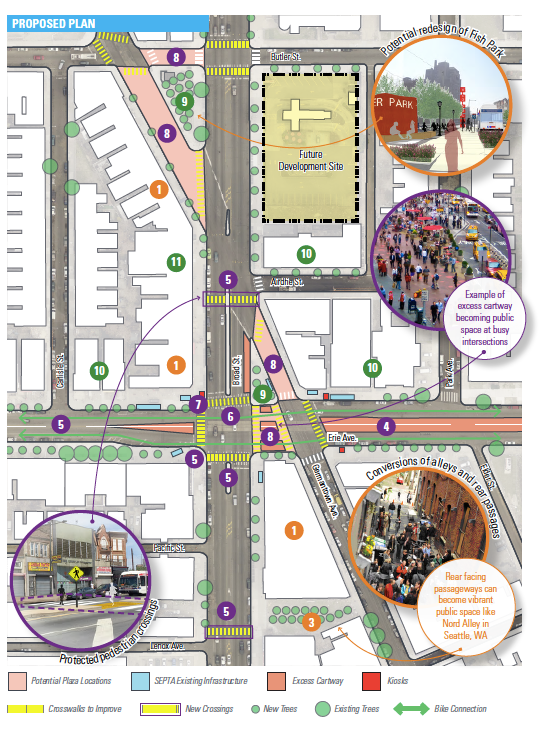

Another focus area is the bustling intersection at Broad Street and Erie Avenue, which is crowded with shops and restaurants but seriously lacks safety infrastructure for pedestrians, drivers, or bicyclists.

“We want to help bring it back as a thriving downtown of North District,” said Richards. “The place is so busy it feels like Manhattan. But there are no trash cans, for goodness sake.”

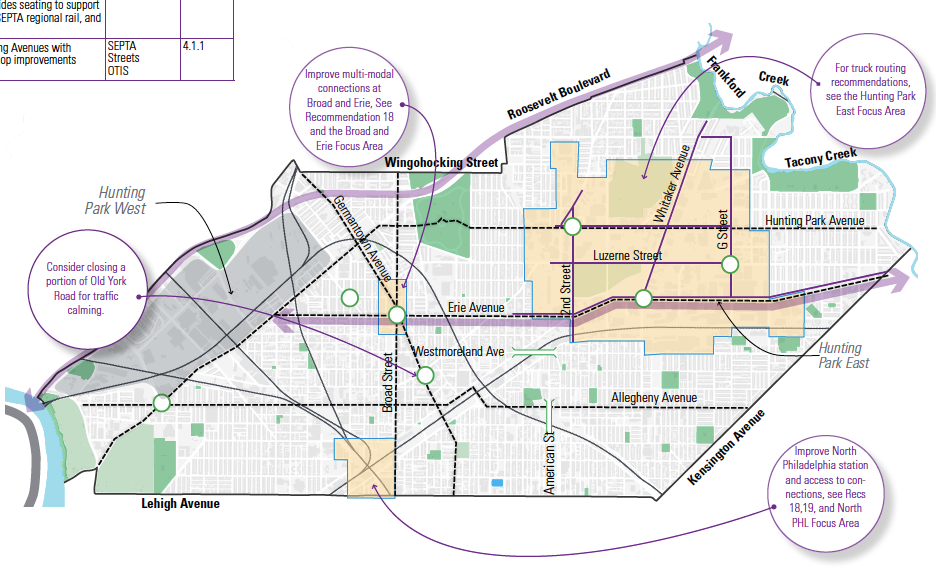

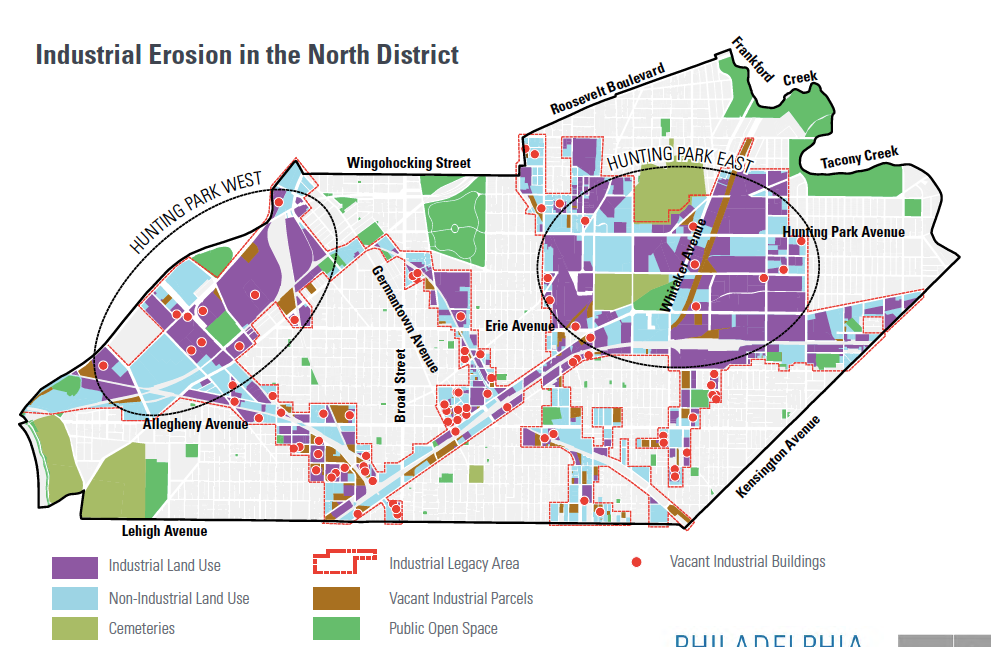

The final focus area is Hunting Park East, a vast swathe of former and current industrial buildings that needs to be brought up to date to reflect current economic realities. Richards says both remapping and traffic safety studies are being proposed to address today’s needs.

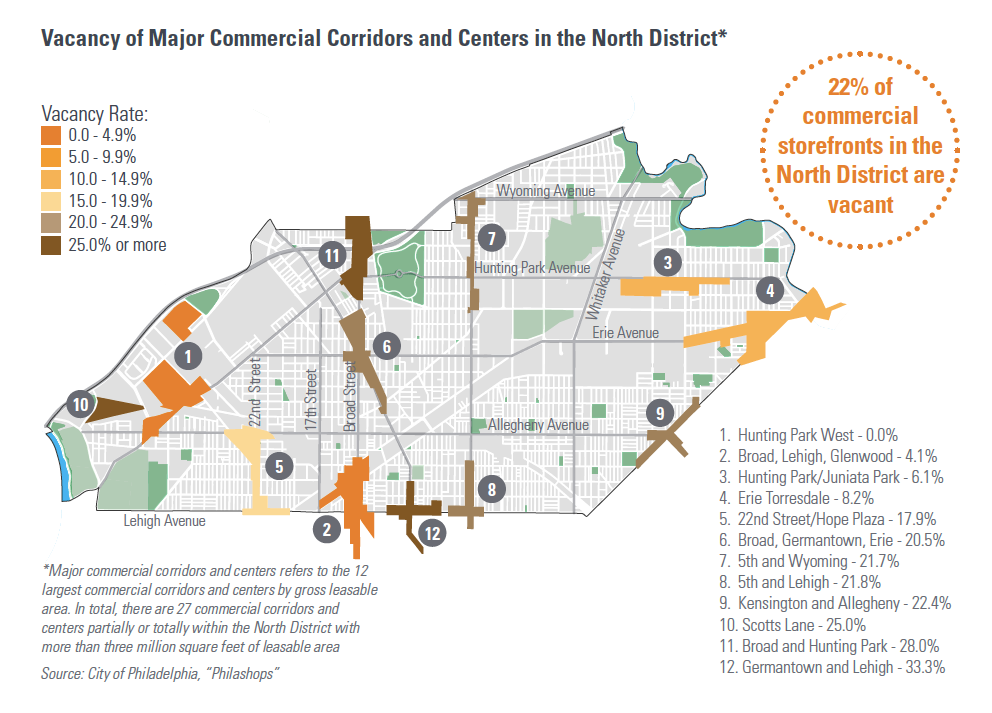

The commission’s other plans for the North District include a massive downzoning from multi-family to single family of the area’s many rowhouses neighborhoods. (Like much of the city, North Philadelphia was zoned for multi-family housing during the 1950s when the population was projected to grow beyond its 2.1 million peak; instead it lost 600,000 people.)

This proposed remapping would be strategic, with areas like Tioga — which contains many Victorian townhomes — remaining zoned for multi-family because the community’s huge houses are far too expensive for most single families to maintain. Other proposed remapping includes upzoning along commercial corridors and around transit stations (including but stops) and some industrial zoning tweaks to reflect the vanishing of heavy industry.

The commission proposes downzoning many corner stores to curb the growth of “stop-and-go” stores, which feel like a corner beer shop or bodega, but sell cheap shots of hard liquor. Some community activists feel that stop-and-go stores, more so than a corner bar, encourage drunken loitering. Richards describes it as “a strategic rezoning to CMX-1, which doesn’t allow for restaurants.” Stop-and-go stores are technically restaurants under state liquor regulations, which require a place for people to sit down and eat.

The Planning Commission is also recommending a series of transportation safety upgrades. The North District lacks many north-south bike lanes, while the neighborhoods east of Broad — which also play host to heavy trucks servicing the remaining industries — also suffers from a shortage of bike infrastructure. The intersection of Broad and Erie is one of the most crash prone in the city and lacks adequate crosswalks (not to mention an elevator or escalator down to the subway station). There aren’t any bike share stations in the district.

The North District proposals were presented in two rows of back-to-back posters, offering the commission’s findings and proposals in Spanish and English. The North District, which stretches from Kensington Avenue to the east to Roosevelt Expressway in the west, is majority African-American with a large minority of Latino residents concentrated in its eastern reaches.

This meeting, held at Temple University’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, is far from Kensington and the room notably congregated around the English-language placards. An interactive map at the entrance asked respondents to show where in the district they were from and demonstrated that almost all of the attendees were from the neighborhoods just to the north of the medical school.

“It looks great and obviously a lot of work went into this,” said Julia Lavender, a member of the neighboring Zion Baptist Church. “All of this is so detailed, showing how it will be, like on the Home and Garden Channel. You can look at it and just visualize what it will look like.”

Like many of the attendees, Lavender attended out of general curiosity, but still sought answers about her particular neighborhood concerns. Her church is contemplating writing a historic nomination for the Leon Sullivan Community Center, across Broad Street from Zion Baptist, and she came to seek more information about the historical designation process.

Hakim Hopkins, owner of the iconic Black and Nobel bookstore, attended as well. The shop, with it’s huge “WE SHIP TO PRISONS” banners, is a staple of the Broad and Erie commercial corridor. But in recent months he’s been struggling to keep the doors open.

Hopkins says he would be excited to see more attention paid to the intersection. He hopes the apartments planned for the Beury Building, and the planning commission’s hopes for an expanded public library and more crosswalks, might increase foot traffic.

“You can see it’s official,” said Hopkins, gesturing to the placards and renderings. “It would be good to have it [the commercial corridor] looking up. It’s the center of the city.”

Hopkins discussed Black and Nobel’s future with state senator Sharif Street, one of several political figures who made an appearance at the event. Other representatives included Jeffery “Jay” Young, legislative counsel to council president Darrell Clarke — the only one of the four city council district offices that cover the North District to send a representative. The developer SGA, which is working on the North Philadelphia Station proposal, also sent a representative to the meeting.

Community feedback for the planning process has focused on issues of employment, health, and blight. The poverty rate for North District is 46 percent and median income is $22,241, but homeownership remains almost as high as that of the city as a whole, at 52 percent. At Monday night’s event, post-it notes reflected community concerns about smaller-scale issues too, like more lighting on street corners, sidewalk repair, and benches at every bus stop. Eighty percent of district’s transit riders ride the bus.

“We tried to stay attuned to what the community was saying, but also to what they weren’t saying and who wasn’t in the room,” said Richards.

The draft plan comes out on October 17. The last day for public comment on the North District plan is November 14.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.