Handwringing over handwriting is not preparing Philly students for the future

The lack of cursive writing instruction in the city’s schools prompted chagrin from several City Council members at a recent meeting But it seems to me we have more basic business at hand.

The handwriting wasn’t on the wall.

Or in those marbled black-and-white composition books.

Or, as it turned out, anywhere in the required curricula of Philadelphia’s 142,000 public school students. And that — the lack of cursive writing instruction in the city’s schools — prompted chagrin from several City Council members at a recent meeting.

At least five Council members raised the topic of handwriting instruction at the late-May meeting, with Councilwoman Blondell Reynolds Brown declaring that “cursive writing should be mandatory.”

I can only imagine the thought-balloons — lettered in Roman all-caps, with exclamation points — that popped into school officials’ heads. The school folks were there, of course, for what has become a sad and infuriating springtime ritual: the annual beg for funds to keep a threadbare school district from fraying entirely.

This is a district, remember, with a 25-percent dropout rate. In which 37 percent of students scored “below basic” in the 2014 PSSA reading test and 35 percent were below basic in math. It’s a district that has 11 librarians for 218 schools.

The day of that May meeting, Superintendent William R. Hite had a big ask: $103 million in new, recurring revenue from the city. So you can understand his surprise when the discussion was sidetracked by queries about whether students are learning to mind their Palmer Ps and Qs.

Or perhaps he shouldn’t have been startled. The handwriting debate points to a profound uncertainty — shared by teachers, parents, administrators and policy-makers — about the mission of public schools. What should we be teaching? What does a 12th-grader on the verge of graduation (or a kindergartener who, if all goes well, will leave school in 2027) really need to know?

Let’s put some historical spin on that question. A hundred years ago, students who wished to graduate from 8th grade in Kentucky had to diagram the sentence, “The Lord loveth a cheerful giver,” tell what they knew of the Gulf Stream, name the inventors of the cotton gin and the telegraph and answer the question, “Why should we study physiology?”

Want something a bit closer to home? In Lower Merion public schools, a few short decades ago, I did indeed learn cursive writing—along with shorthand, Shakespeare and how to make a fruit ambrosia with mini marshmallows and sour cream.

I’m certain my teachers believed they were preparing me for life in the 20th century. But who could have predicted that, by the time that century sped to a close, I’d need to know how to conduct a Google search, create a PowerPoint presentation and compose rapid texts on a device the size of a graham cracker?

It’s tough to educate kids in the present for a future we can’t envision. We can teach them as we were taught, leaning on a familiar scaffolding of content (classic literature, Colonial history, algebra, biology), or we can take three giant steps back and think broader and deeper, with an understanding that the best we can do is prepare our kids to be flexible thinkers, collaborative learners and discerning citizens in a world that moves wildfire-fast.

Those City Council members who perseverated over handwriting might argue that some elements of education never go stale. Surely students must learn the multiplication tables, or the difference between subject and predicate, or the capitals of all 50 states.

Perhaps. But at the first back-to-school night at my daughter’s academically rigorous public middle school, as I listened to parents who hailed from all parts of the city (and, indeed, all parts of the world; kids in that class had roots in Albania, Korea, Italy and Greece as well as South Philly and Somerton), it was clear that we did not agree on what those “essential” elements of education might be.

While I would have welcomed a more progressive approach—inquiry-driven, project-based—other parents were agitating for their kids to memorize spelling words, read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and, yes, write in script.

If it’s any comfort, the nation shares our local lack of consensus. Just witness the furor over the Common Core, an initiative launched in 2009 by U.S. governors and state commissioners of education to develop a set of “high-quality academic standards in mathematics and English language arts.”

Not so fast. The Common Core, adopted by 43 states and the District of Columbia, has endured flogging from both the conservative right (arguing for less federal sway over local curricula) and the liberal left (claiming the Common Core devalues the whole child and robs the curriculum of art, music and play).

It’s worth taking a look at the actual Common Core standards: eighth-graders, for instance, should be able to compare a filmed or staged version of a story with the original text, evaluating choices made by the director or actors. They should “distinguish among fact, opinion and reasoned judgment in a text.” They should be deft at researching both print and digital sources.

Not a word about the Gulf Stream or the telegraph. And not a word, in that grade’s standards or in any other, about cursive writing.

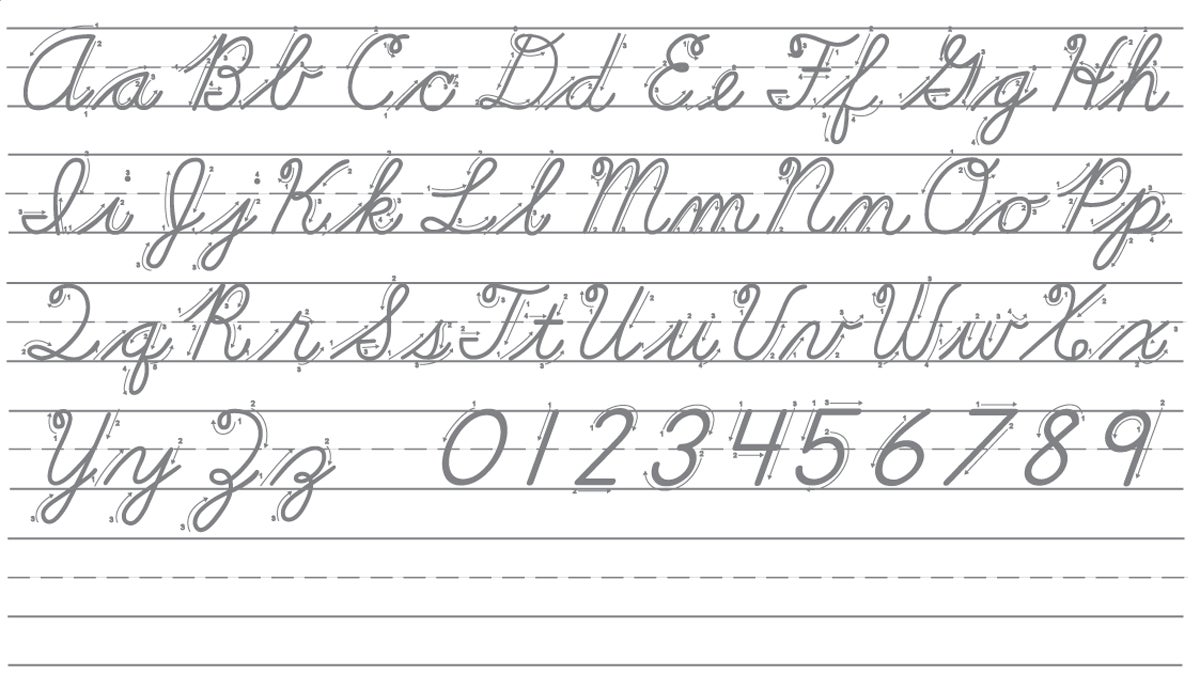

Handwriting advocates argue that the tactile experience of learning cursive, with its looping, connected letters, activates certain brain pathways. But all learning—even that sticky fruit ambrosia, which required measurement, physical dexterity and cooperation with my home ec team—animates brain pathways. Who’s to say which ones will serve us most nimbly in the long run?

It’s true that if third-graders spent half an hour a day learning to read and write in cursive, they’d be able to decode an original copy of the Declaration of Independence. But if they spent that same 30 minutes learning Spanish, they could communicate with 37 million of their own country’s residents.

Honestly, I’d welcome some genuine discussion — in City Council or, even better, school-based “town hall” meetings — about the experiences and skills we’d like to see our kids possess before they toss those tassels to the other side.

But it seems to me we have more basic business at hand. We have schools with leaking ceilings and moribund libraries, schools in which a student having an asthma attack must appeal to a secretary, schools filled with outdated textbooks and demoralized teachers. Statewide, the funding gap between rich and poor school districts is one of the worst in the nation.

This Saturday, people of faith from across Pennsylvania will gather in Harrisburg to argue that fair, full school funding is a matter of moral justice. We can’t know what the future will demand of us: what aptitudes, what adaptations. But we do know that, eventually, that future will be in the hands of today’s third-graders.

If you’re heading to the rally, bring a sign. I’d advise block letters — big ones the legislators can see from where they sit.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.