Emails show how much pull political bosses had over N.J. state tax breaks

State officials scrambled to meet the demands of a lawyer at the firm where Philip Norcross, the brother of N.J. political boss George E. Norcross III, is managing partner.

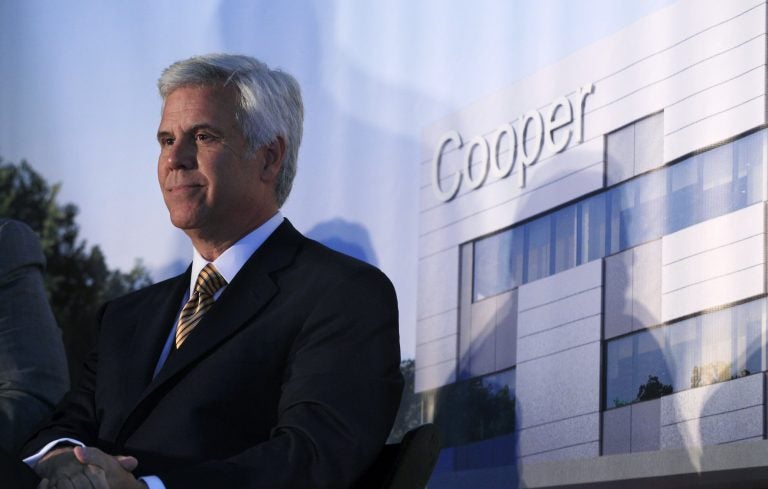

Cooper University Hospital board chairman George Norcross III listens in Camden, N.J., Tuesday, May 15, 2012, during a groundbreaking ceremony for the Cooper Cancer Institute. (Mel Evans/AP Photo)

A law firm linked to New Jersey political boss George E. Norcross III enjoyed extraordinary influence over the state’s tax break program, crafting new rules and regulations in hundreds of calls, meetings and messages with top officials in Trenton, newly released emails reveal.

The emails, obtained by WNYC and ProPublica through a public information request, provide a rare look at how the Norcross family machine leveraged its access to top state officials to advance the interests of clients and friends allied with the political leader. The lawyers pushed officials at the New Jersey Economic Development Authority for client concessions, pressed staffers for expedited reviews and went over their heads to appeal objections.

Kevin Sheehan, an attorney with Parker McCay, where Norcross’ brother Philip is managing partner, focused on getting bigger tax breaks for the Philadelphia 76ers, Cooper Health System and nuclear services giant Holtec International, which won some of the most lucrative tax awards in state history. The companies were promising to move to downtrodden Camden as part of a renaissance pushed by George Norcross, a Democrat whose insurance brokerage was among the tax break recipients.

Sheehan phoned or emailed EDA chief Tim Lizura nearly every day. He arranged dozens of meetings and conference calls with Lizura’s lieutenants and lower-level staffers, who spent hours consulting with the lawyer and working out financial projections and various development scenarios for his clients.

Sheehan also communicated with top officials at former Gov. Chris Christie’s Department of the Treasury and the Attorney General’s Office, which advised him on questions raised by Parker McCay clients. At Sheehan’s request, Lizura advised Sheehan on how tax break winners could sell their credits to raise capital, passing along the names of financial contacts.

When necessary, Sheehan brought in Philip Norcross for leverage, and he also contacted the office of Christie, a Republican aligned with George Norcross in bolstering the tax incentive program to encourage job creation and retention.

Sheehan made a growing list of changes he wanted to make to a brand new law that offered tax breaks to companies willing to invest in new jobs, the emails suggest. “Thanks Kevin,” Christie administration senior counsel Colin Newman wrote to Sheehan in June 2014 after reviewing language the lawyer suggested in a tax credit “cleanup” bill.

“A copy of the bill incorporating all the changes we previously discussed would be very helpful,” Newman wrote. The bill passed in October 2014 and included extra bonus credits for specific companies, a lessening of the hiring requirements and changes to what kinds of businesses are eligible for the tax break.

The newly released documents comprise 12,000 pages in all and cover 18 months between September 2013 and February 2015.

But Kevin Marino, an attorney for Sheehan and Parker McCay, said the volume may leave a misleading impression of the extent of Sheehan’s communications with the agency. The documents include many emails on which Sheehan was merely copied and others that contain long attachments, Marino said.

“I am absolutely confident that Parker McCay and Kevin Sheehan have behaved lawfully and ethically with all their interactions with the EDA,” said Marino, who also represents George Norcross.

However, the emails illuminate possible irregularities in how the program was administered by the state, a charge that has prompted investigations and at least one criminal referral from a special task force appointed this year by Gov. Phil Murphy, who is also a Democrat. It has not been disclosed who is the subject of the criminal referral.

On Tuesday, George Norcross, Parker McCay and other entities affiliated with the Norcross family sued Murphy, arguing the governor “unlawfully empowered the task force with powers he did not possess and authorized the retention and payment of New York lawyers who proceeded to commence and conduct an investigation in violation of multiple provisions of New Jersey law.”

The task force has said that EDA regulators at times did not rigorously verify financial information submitted by applicants and accepted claims that other states were trying to convince them to relocate. Verifying such claims is crucial because the law says companies may only receive breaks after documenting competitive offers from other states.

One EDA staffer, responding to a question from Sheehan about potential tax breaks, suggested that his client produce documentation comparing alternative locations. “Perhaps he can produce a cost benefit analysis comparing the Philly site [to Camden] but it wouldn’t have to be too in depth,” the staffer wrote.

The new details about Sheehan’s role in steering state policy go beyond recent allegations made in task force hearings about the generous tax breaks, which Murphy has panned as an “$11 billion black hole.”

Spurred by a state audit that found major flaws in the program, Murphy appointed the task force to investigate possible program fraud. In its first months, the task force has heard from company whistleblowers and focused attention on awards made to South Jersey companies affiliated with George Norcross.

The party leader and his many allies have responded with a barrage of criticism aimed at the governor and have defended the Camden developments. They argue that the program is more generous to projects in Camden because, as the poorest city in the state, it needs the most help. But state records show Norcross has been a main beneficiary of the tax breaks.

WNYC and ProPublica reported this month that more than $1.1 billion of the $1.6 billion committed to tax breaks in Camden so far went to companies owned by or affiliated with George Norcross or tied to Philip Norcross, who is also a lobbyist representing firms that have collected tax awards.

“This is the first thing that was needed to happen, to move people to the city of Camden in order to help create jobs and create an influx of activity in the city which would hopefully draw some private capital investment,” George Norcross said.

In a December 2013 email inquiring about possible tax credits for a Camden charter school founded by George Norcross, Sheehan reminds Lizura about new regulations that could benefit Cooper Hospital, which is chaired by Norcross. At that time, companies providing retail jobs were not eligible for tax breaks. Cooper Hospital had no immediate comment.

“My suggestion would be to add a sentence at the end of the definition to say: a university research hospital shall not be considered final point of sale retail,” Sheehan wrote.

The New York Times reported this month that Sheehan helped draft sections of the 2013 Economic Opportunity Act that specifically benefited his clients.

Lizura declined to be interviewed for this story. In a statement sent by his lawyer, he said, “During my tenure at the EDA, we routinely worked with companies and their representatives to provide them with feedback regarding the requirements of the program, and to assist them with their applications, consistent with the EDA’s purpose of encouraging job growth and economic development in New Jersey.”

The emails show Sheehan successfully pressed state officials for new rules to protect companies that bought tax breaks from the original recipients. The tax break law calls for “clawbacks” — or a return of money — if a project supported by tax credits fails to create promised jobs.

Sheehan suggested in a May 2014 email, and elsewhere, that language be added to the state administrative code to protect tax credit purchasers from “recapture” by tax agencies. He said such language would help Norcross law firm clients, such as Holtec International and Eastern Metal Recycling, sell their tax credits. The two companies later received tax breaks totaling almost $400 million. At times, the emails suggest, staffers at the EDA and other state agencies pushed back.

In May 2014, for example, EDA development officer Justin Kenyon declined Sheehan’s request to perform a time-consuming “net benefit analysis” for Eastern Metal Recycling as the company considered applying for tax breaks. Eastern Metal Recycling, Sheehan explained, wanted to know how big the tax award might be.

In one case, he asked a staffer for a five-day turnaround and was told the review normally took six weeks. Sheehan took his case to Lizura, Kenyon’s boss, and got the approval letter he was seeking two weeks later.

Sheehan barraged the state with requests, demands for meetings and special client inquiries. He advocated for the cost of architects, insurance or permit fees to be calculated as a capital expense, which would raise the total tax break significantly in some cases.

In some email exchanges, Lizura pushed back and prevailed. But in several instances, the rejection of a request resulted in Sheehan enlisting the help of Philip Norcross to win a meeting.

“Can Phil and I meet with you this week to discuss this issue? Preferably Wednesday or Thursday,” Sheehan wrote to Lizura.

EDA staffers rushed to meet Sheehan’s deadlines but sometimes found that applications from his clients lacked key information. The EDA acknowledged emailed questions Tuesday but has yet to respond.

Reviewing Cooper Hospital’s application for $39.9 million in tax breaks in November 2014, staffers found that it lacked a cost-benefit analysis and certification from the hospital CEO that the tax breaks were essential to keep hospital jobs from leaving the state.

Nine days before the application was approved by the EDA board, the staff was still scrambling to get information from the hospital about the cost of a competing site in Philadelphia.

“I am touring alternative locations in Pa. on Wednesday and hope to have term sheets by the end of the week,” Andrew Bush, a Cooper Hospital executive, wrote to EDA staffer Teresa Wells in an email copied to Sheehan.

Wells wrote back, “Thanks, it is very important that I have some back-up to the lease terms as presented in the Cost Benefit analysis — it’s all verbal at this point?” The application was approved on schedule.

A spokesman for Cooper Health says the questions about an out-of-state location were driven by the EDA staff, who must have been confused about the law.

“It is inconceivable that the EDA would have thought that Cooper intended all along to move jobs out of state,” said Thomas Rubino, senior vice president of communications and marketing for Cooper Health. “ Under the Growth Zone provisions of the statute, firms moving into Camden did not have to show they were considering out of state sites under the net benefits test.”

Sheehan’s largest win at EDA, at least in dollars, was the $260 million tax break awarded in July 2014 to Holtec International, where George Norcross sits as a board member.

The emails record a series of breaks for Holtec and its representatives, whose complex demands spurred the EDA to schedule twice-a-month conference calls with the company.

Holtec’s top demand, the emails show, was to cover the costs of building a new headquarters and manufacturing compound in Camden entirely with tax breaks. “Our ultimate goal is a 1 to 1 ratio of Tax Credits to Capital Investment,” one executive wrote to the EDA.

Holtec set the agency to work calculating possible tax break scenarios based on hypothetical numbers of employees it might bring to Camden. The company also won approval to count employees hired as far back as Jan. 1, 2013, as “new hires” for the purpose of satisfying job creation requirements.

Krishna Singh, Holtec’s CEO, was allowed to withhold his certification of new and retained jobs until days before the final vote, a pace that appears to have irked EDA staffers. “Staff will work diligently through this process, but please be mindful that in other tax credit programs it has been customary to submit the certification 90 days prior to the deadline,” EDA staffer Kevin McCullough wrote to Holtec.

On June 30, days before the board vote, the EDA was still trying to verify how Holtec came up with price estimates for its Camden project.

Sheehan, in a single-sentence email to McCullough, cites figures from the South Jersey Port Corporation, the state agency that owns the waterfront site. The agency’s former chairman is a longtime ally of George Norcross.

Ten days later, the EDA board awarded Holtec the second-largest tax break in New Jersey history. In a congratulatory note, Singh refers to a business fable.

“Thank you, Kevin. Like the proverbial pig, we are now committed to the ham sandwich !!!!”

“Cheers, K.”

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.