Contemplating Philly’s portfolio school model after a year of closures, openings

Listen

A student raises his hand at Isaac Sheppard School in Philadelphia. (Photo by Jessica Kourkounis)

Philadelphia’s public education strategy rests heavily on parents’ having a wide variety of schools and school operators from which to choose. At first glance, offering these rich options seems like a no-brainer.

Closer examination reveals anything but a simple picture. People who care about public education in Philadelphia are grappling with the complexities created by this approach, which is known as the Portfolio Model.

Meditations on this subject lead to an essential question:

How should the city evaluate a system which can give parents better options, but causes systemic instability, leads to the pain of routine school closures, and sometimes leaves neighborhoods without a comprehensive school tasked with serving all students?

Students displaced

The 2014-15 school year brought this question into sharp focus as the city saw sudden mid-year school closures immediately followed by debate about additional school openings.

In December, two low-performing charter schools – Walter Palmer Leadership Learning Partners and Wakisha – ran out of money and closed suddenly just before the Winter break.

This displaced more than 1,500 students and left parents and guardians in a nightmarish scramble to find another option mid-year.

At a time when students should have been sharing stories of their holiday break with their friends, they were instead adjusting to an entirely new set of classmates and teachers.

About 50 of the affected families opted to send their kids to Dunbar elementary, which is in the midst of Temple’s campus.

At a ceremony Dunbar held in January to welcome displaced students, Lisa Hill described how the upheaval affected her grandson. He had been an 8th grader at Wakisha charter, which closed abruptly after years of fiscal mismanagement.

“It’s a mess,” she said. “They have to start all over – meeting the friends and meeting the teachers again. It makes it kinda difficult on the kids.”

While this scenario represents an extreme, this sort of instability is nothing new to Philadelphia.

In fact, it has become an inherent part of the city’s public education landscape as city, state and district leaders have embraced the portfolio model over the past dozen years or so.

Parents can now choose from a diverse array of school options – including neighborhood schools, citywide-admission charters, cyber schools, district-run magnets, or other boutique district schools, all tuition free.

Without doubt, this model has extended lifelines to those parents dissatisfied with the public school in their neighborhood.

But with greater school choice has come greater fiscal and organizational complexity. More schools and more school operators, each with their own bureaucratic infrastructures, have been asked to serve roughly the same number of children.

To make the financials work, something has to give.

So when new buildings open, the added costs come out of the pockets of the remainder of the district’s schools.

Eventually, those inefficiencies lead, indirectly, to the closing of other schools. The city’s educational landscape tilts, and the system hopes the pain to communities of shuttering schools is worth it in the long run.

‘No school wanted him’

An integral feature of the portfolio model is that it trusts a variety of school operators to both serve the needs of children and act as stewards of public dollars.

In theory, the district’s charter office would act as a robust watchdog for the public interest in both cases, but, in reality, the office struggles to do more than the bare minimum because of chronic understaffing.

This has been especially true in the years since former Gov. Tom Corbett eliminated the budget item that reimbursed districts for the added costs of charter schools.

Gov. Wolf hopes to restore this funding. In the meantime, the state continues to take a pass on supporting the added burden of the more complex model it encouraged with the passage of the charter law.

Over the past five years, as charter enrollment has almost doubled, the district’s charter office has been slashed in half. Now just six employees oversee 84 schools serving 62,500 children.

The School Reform Commission is also often hampered by rules at the state level that make intervening or closing charter schools exponentially more difficult than doing so at district schools. This has proved frustrating as some of the charters that were greenlit have fallen drastically short of expectations.

This was the case at Walter Palmer charter, which had operated two different campuses in the city. The severely low-performing school closed in December after being embroiled in a years-long legal dispute with the district over enrollment caps.

That battle had been dragged through the courts for years, until May 2014, when the state Supreme Court sided with the district. The Court ruled that Palmer needed to abide by an agreement it signed in 2005 which capped enrollment at 675 kids.

Up until that point, the Pennsylvania Department of Education had been deducting money from the school district to pay for students enrolled above the cap.

Despite the Supreme Court ruling, Walter Palmer decided to open his school in September with 1,300 students knowing that – barring a legal hail mary – the school would only receive funding for 675.

School founder Walter Palmer (Kevin McCorry/WHYY)In October, the school made a few last-gasp efforts to remain open. Palmer held a lottery to whittle 250 students out of its elementary school, and then, the next week, suddenly closed the high school campus.

By December, Palmer’s gambit proved futile. Funds ran dry, and the entire operation was shuttered.

Parents received letters the weekend before Christmas informing them that their children could not return. Shanae Jones’ first-grade son Anthony had attended the elementary school.

She, too, spoke at Dunbar’s welcoming ceremony.

“We’re working families out here just like everyone else,” said Jones, who was particularly upset about spending money on now obsolete Palmer uniforms. “I feel like he owes us.”

Dunbar schedules its day differently than Palmer had, so making the transition meant Jones needed to adjust her own work and college schedule as well. She holds down a full-time job while earning credits at night toward a degree in criminology at Penn State Abington.

“I was just so frustrated with the whole situation,” she said.

Many charter schools don’t accept new students mid-year, so the majority of the displaced students ended up in district schools – adding significant social and pedagogical challenges to the receiving schools.

|

Senior Iyonna Conner did end up in another charter. She moved from Walter Palmer’s High School campus to Math, Civics and Sciences charter school in Center City.

“I came home. My mom said I had to leave,” said Conner. “I started crying, but then I just said, ‘Ok.'”

A couple miles away, in Philadelphia’s Fairmount neighborhood, Bache-Martin elementary also saw an influx of students from Palmer charter.

Parent Jihan Pauling said her first-grade son has since adjusted, but took the initial announcement hard.

“He just kinda felt like he didn’t know where he was going to go to school, like why would they close his school, like what did he do wrong?” she said. “He just didn’t understand why no school wanted him.”

Winners and losers

The term “portfolio model” comes from the idea of an investor’s stock portfolio. The investor purchases stock in a diverse array of companies, tracks growth and performance over time, and then doubles down on the blue chips and sells off the underperformers.

In education, the portfolio model means the school system invests resources in a variety of school operators – not just one centralized, monolithic school district.

Proponents say that giving parents more choices creates competition and spurs innovation that can provide many kids a safer, better education.

Detractors criticize the model because it often favors opening new schools and closing low-performing ones rather than improving them.

The teachers’ union laments this, in part, because of the threat this poses to unionized jobs.

Systemic concerns, though, have arisen too.

As underutilized schools eventually close, whole neighborhoods can be left without a comprehensive school tasked with serving all students. It also becomes more common for young children to traverse the city in order to attend school.

“What happens when you have the amount of choice that we’re beginning to see in a city like Philadelphia is that you lose that potential strength for a community,” said Kate Shaw, executive director of Research for Action.

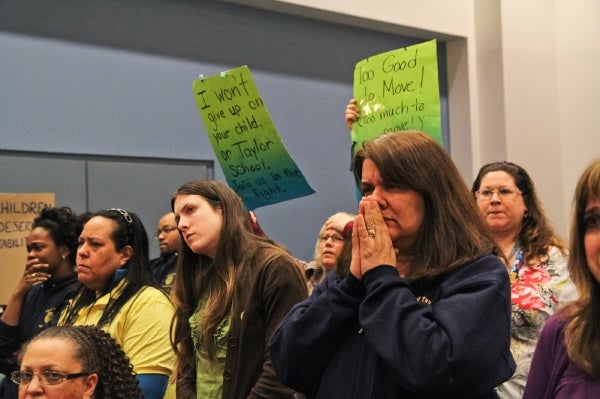

Taylor Elementary School parents during a March, 2013 SRC meeting (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)In 2012 and 2013, the School Reform Commission shuttered 30 of the district’s lower-performing schools. They did so in large part because, with the rise of charters and magnets, many of those schools were half empty – creating unsustainable budgeting inefficiencies.

Taylor Elementary School parents during a March, 2013 SRC meeting (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)In 2012 and 2013, the School Reform Commission shuttered 30 of the district’s lower-performing schools. They did so in large part because, with the rise of charters and magnets, many of those schools were half empty – creating unsustainable budgeting inefficiencies.

Those logistics, though, did not make the action any less difficult for the students, parents and other stakeholders who had grown emotionally attached to the schools on the chopping block.

Students of University City High School react to the news that their school will be closing during a March 2013 SRC meeting. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Students of University City High School react to the news that their school will be closing during a March 2013 SRC meeting. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This year’s two mid-year charter closures brought turmoil as well.

Shortly after it became clear that Walter Palmer’s high school campus would be shuttered, sparks flew at a meeting between parents and school officials in the basement of the Harbison Avenue campus.

Grandparent Rashida Jabbar was one of several caretakers crying and screaming at Palmer at the meeting.

Insider’s take

The Philadelphia School District takes a nuanced view of how the rise of the portfolio model has affected students and parents.

Compared to a decade ago, assistant superintendent Paul Kihn says “there are a fair number of students and families who are now in much better schools” – both district and charter.

Crucially, Kihn believes the rise of the charter sector has spurred the district to more intently evaluate and improve its own offerings.

In the past decade the district has aggressively expanded its high school options – favoring smaller schools that appeal to niche interests. In this vein, at the beginning of this year, the district opened three new non-selective, projected-based high schools in North Philadelphia.

But Kihn agrees that it’s a “tragedy” when communities lose their neighborhood schools as byproduct of expanding school choice.

“If you are removing schools or not allowing schools that are neighborhood schools to improve, you’re actually removing the choice that parents and families would most like to have – which is a good school close to where they live,” said Kihn.

Complicating the matter further are the financial considerations.

Kihn cited Washington D.C. and Denver as cities where state funding models better account for the additional fiscal supports required to adequately support a portfolio approach.

“In Philadelphia, it’s really tough because it’s almost like you’re benefiting some on the backs of many,” he said. “You have to account for the damage that’s done across the system.”

Silver lining?

Some who advocate for education reform favor the portfolio model for its ability to force swift change.

They say instability is well worth it in the short-term as long as children end up in higher performing schools.

“We live in a city with limited resources for education. And in a situation of limited resources, we need to be prioritizing schools that are working for kids,” said Mark Gleason, executive director of the Philadelphia School Partnership, a major proponent of the portfolio model.

Gleason wishes the district could have worked out an agreement to avoid mid-year closure with Wakisha and Palmer, but he believes there’s a silver lining.

“The positive here is that we’re going to shift the resources that were going to those schools into schools that can hopefully do a better job,” he said.

Gleason argues that Philadelphia has retained its population over the last decade because it became a hub of charter and magnet school innovation.

“The answer shouldn’t be: let’s not close schools,” he said. “The answer should be: we need a better policy for how schools close so that it happens at the end of the school year.”

|

Above is a breakdown of the demographic data and state school performance profile scores of the schools mentioned in this story.

Attempts to strip the district of control

In recent years, state lawmakers have sought to strip the Philadelphia School District of its ability to manage the growth of the city’s portfolio.

In February, just as parents and students at the two suddenly closed charters were adjusting to their new schools, the city found itself in the midst of another high-stakes school choice debate spurred by Harrisburg.

In an amendment to the bill that allowed Philadelphia to fund schools with a city cigarette tax, state lawmakers required the school district to end its moratorium on new non-neighborhood-based charter expansion.

Forty applications for new charters were submitted to the School Reform Commission. With a potentially game-changing number of new operators vying to join the city’s portfolio, education advocates and politicians argued over the effects that such growth could have on children.

Newly sworn-in Gov. Tom Wolf advocated for zero new charters to be approved, as did several of the city’s education advocacy organizations.

Top state Republicans pushed for a wave of expansion, as did Gleason’s PSP, which offered $25 million to the school district to help cover some of the added costs of charter growth.

In the end, the SRC voted to approve six new charters. Pennsylvania Speaker of the House Mike Turzai (R- Allegheny) had advocated for opening 27 new schools – making no mention of the corresponding closures that would likely occur.

After the SRC’s decision, PSP’s advocacy wing, Philadelphia School Advocacy Partners, engaged in a $1 million advertising campaign calling for greater charter expansion.

Other attempts to outsource control of the city’s portfolio have regularly cropped up in the capitol over the past few years.

A bill introduced in 2013 by Sen. Anthony Hardy Williams (D-Philadelphia) hoped to give Pennsylvania colleges and universities the authority to open new charter schools anywhere in the state.

In April, Sen. Lloyd Smucker (R- Lancaster) introduced a bill which would give a state board unilateral power to convert low-performing district schools to neighborhood-based charters in what he calls an “achievement district.”

In both cases, district leaders objected to further state interference – especially because neither bill provides additional resources to cover the stranded costs of additional growth.

In an interview shortly after Smucker presented his bill, Superintendent William Hite expressed his opposition to the legislation – explaining that budgetary concerns make him wary of additional charter conversions.

“If in fact we could do more of these we would have,” said Hite. “It wasn’t governance that kept us from doing that; it was revenue.”

Smucker’s bill, which PSAP helped frame, would also make it easier to shutter low-performing charters.

Moving forward, Hite and his team warn against rapid expansion or decline in either the district or charter sector.

“If you want to be on the side of what’s best for students and families in the city of Philadelphia,” said Paul Kihn, “you’re going to be on the side of some degree of stability while the district works hard in the way that we’re currently doing to improve our schools.”

As budget negotiations in Harrisburg continue, Kihn’s request seems like a long shot.

Republican leaders in the legislature are not likely to grant Gov. Wolf’s proposals to restore recession-era education funding cuts without demanding additional accountability measures.

To Kihn’s chagrin, in those conversations, Smucker’s “achievement district” bill may become an important chip.

“Schools are fairly complicated organizations, but we basically know how to improve them,” said Kihn, “and so many of us are distracted by the wrong kinds of discussions that we’re not given the space or the time to work on making the schools great.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.