City leaders send stark message to Nutter: Collect taxes

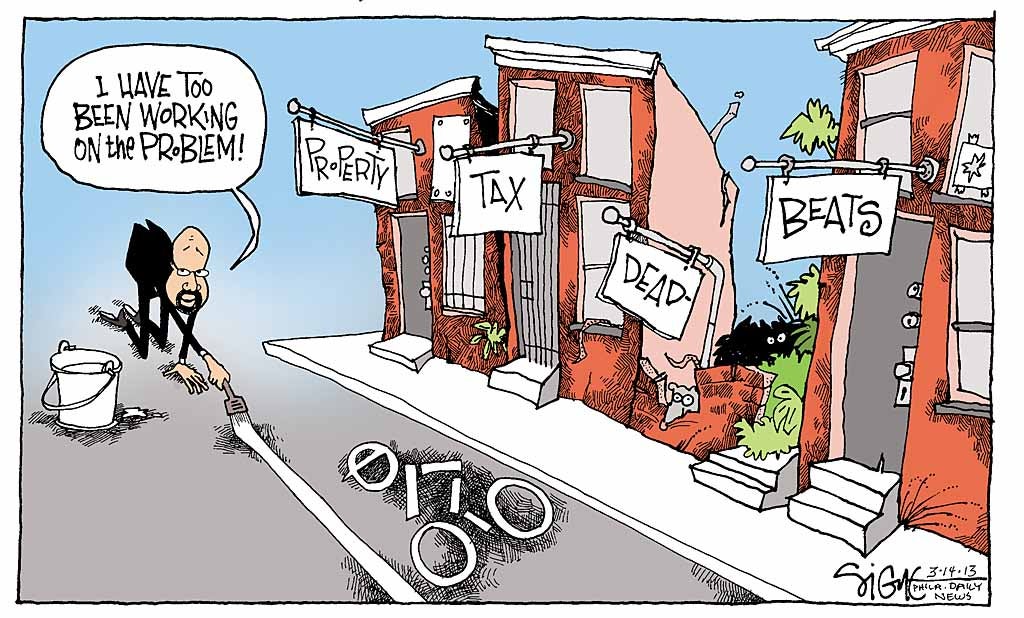

Two days before Mayor Nutter is scheduled to deliver his budget address, a host of city leaders called on his administration to improve its performance in the collection of delinquent property taxes.

Philadelphia’s delinquency crisis – the subject of a three-day PlanPhilly/Inquirer series published this week – has been a matter of growing interest in city government circles for some time. But with the pending transition to a new property assessment system – a move that will lead to higher taxes for many homeowners – delinquency has become a politically explosive subject.

City Council will hold at least six hearings on property tax delinquency in coming weeks, and there are a host of legislative proposals – in Philadelphia and Harrisburg alike – that aim to get a handle on the delinquency epidemic. They include a land bank, the liening of property outside city limits, and developer inducements in highly delinquent neighborhoods.

The sense of urgency is being driven by two concerns: the fiscal plight of the school district, and political pressure from homeowners worried about the Actual Value Initiative.

In a written statement to the Inquirer and PlanPhilly, Mayor Nutter said on Tuesday that “tax delinquency is a significant problem for Philadelphia. It has been for 30 to 40 years, and frankly, the recession made collections even more difficult.”

Nutter said in the statement that the city had not invested enough in tax collection because of tight budgets.

“But since our (2010) tax amnesty, from which we collected more than $72 million, we have improved our collections in the last two years as the Law and Revenue departments worked more closely and more aggressively using our private collection entities,” Nutter wrote. We’ve collected more and we’ve made much greater use of sheriffs sales.”

The mayor said that “we must do more and we will,” referencing a series of new tax collection strategies he outlined in February, including a $40 million investment over five years in new staff and technology for the Revenue department.

“I believe citizens will see and tax delinquents will feel the results of improvements in collections this year,” Nutter wrote. “We can and will significantly improve, but we must invest now in new initiatives as we’ve outlined in our proposed budget and new Five Year Plan.”

It remains to be seen how City Council will respond to Mayor Nutter’s request for new Revenue department funding. While they share his interest in improving collections, they seem less sure that significantly increased spending in Revenue is the way to achieve that goal.

City Council President Darrell L. Clarke said he “will not be supportive of a $40 million investment that shows no return on investment,” meaning that if Nutter wants more money for revenue, he should present a budget that assumes improved delinquency collections.

Clarke said that council members are frequently barraged with questions by constituents about the city’s poor record on property tax collections.

“This comes up at every community meeting,” Clarke said. “’What are you doing about people who won’t pay their taxes? It’s not fair for you to ask me to pay more when there are people who aren’t paying their fair share.’”

The Inquirer and PlanPhilly series documented the tremendous full costs of the city’s delinquency crisis, which include a $9.5 billion hit to the property tax base and an average 22.8 percent decline in the value of single family homes with delinquent neighbors. The series showed how it is investors – not owner occupants – who account for a majority of all delinquent accounts and 69 percent of the total outstanding principal, penalties and interest debt owed to the city and school district on unpaid real estate taxes.

Under the Nutter administration, the city’s delinquency crisis has deepened. The three worst collection years since 1980 have all been logged on Nutter’s watch, and Philadelphia’s collection rate has fallen further behind other large cities.

“The series is like several barrels of oil thrown into a raging fire. It complicates everything. How do you justify doing this (AVI) when you’re not doing that (delinquent collections)?” asked Sam Katz, chairman of the Pennsylvania Intergovernmental Cooperation Authority, which oversees Philadelphia’s long-term fiscal planning.

“I don’t know what there is to debate. I hope that the city and the mayor and City Council and the Department of Revenue get behind a concerted effort to take this issue off the table, because it really is debilitating to the people who pay taxes to read stuff like this.”

And yet some see an opportunity for the city to correct some long standing land management problems all at once.

“This detailed examination of tax delinquency is an extraordinarily important complement to the recent work of the Office of Property Assessment in carrying out a comprehensive and long-overdue re-evaluation of all real estate in Philadelphia,” said Center City District President Paul Levy. “Both provide the Nutter Administration and City Council with the opportunity to set many things right and bring Philadelphia into the 21st century.”

Former Managing Director Phil Goldsmith worried that the city’s high delinquency rate makes it harder to win increased state support for the school district.

“You think we’re going to get money from Harrisburg now for the schools? This is just one reason why the people out there will say ‘get your act together before you come to us asking for money.’ And it’s hard to argue with that,” Goldsmith said.

School Reform Commission Chairman Pedro Ramos – who was appointed to his position by Gov. Corbett – said that it was crucial that the city improve its tax collection performance, given the district’s massive structural deficit, which persists even after a series of painful cuts, including the closure of at least 23 schools.

”Given the school district’s financial problems, better collections are definitely necessary,” said Ramos, who, as a former City Solicitor and Managing Director is well acquainted with the challenges of collecting property taxes in Philadelphia.

When Ramos was solicitor – a position that at the time was partly responsible for collections – the city posted the highest collection rate of the last 25 years. “It took a whole lot of effort to move the needle on collections,” Ramos said.

“The foreclosure system has to have teeth for all the effort that goes before it to be credible, and for taxpayers to understand that there are consequences.”

Philadelphia City Council members were similarly critical, some angrily so.

“They tell us they’re doing their best,” said First District Councilman Mark Squilla. “But so far we haven’t seen any real operational change or increase in collections.”

Like Squilla, Councilman Kenyatta Johnson of the Second District represents an area of the city where AVI will increase the tax burden on many homeowners, which makes him particularly sensitive to constituent complaints about delinquency.

“It’s insane that we have issued more than 10,000 licenses and permits to tax delinquent properties over the last five years,” said Johnson, citing one of the findings in the Inquirer and PlanPhilly series. “That adds insult to injury.”

The City Code prohibits granting licenses and permits to tax delinquents not in payment agreements.

Councilman Wilson Goode Jr., an at large member, said the city should target delinquent investors and speculators, adding “the city’s enforcement approach needs to change on a number of different levels.”

And at-large City Councilman James F. Kenney lambasted the city’s Department of Revenue, which shoulders most of the tax collection burden. “It needs to be dismantled or replaced,” Kenney said. “We should be more like the IRS and less like we are.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.