China regulates fentanyl in hopes of stemming supply to U.S.

Most of the powerful synthetic opioid comes here from China. Officials hope strict new rules will curtail the flow that’s driving overdose deaths.

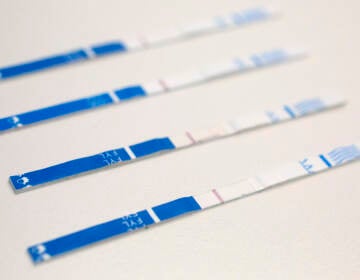

A reporter holds up an example of the amount of fentanyl that can be deadly after a news conference about deaths from fentanyl exposure, at DEA Headquarters in Arlington Va., Tuesday, June 6, 2017. (Jacquelyn Martin/AP Photo)

The powerful, synthetic opioid fentanyl has been the driver of most overdose deaths in Philadelphia and across the country for the past two years. It has infiltrated most of the heroin supply here, and is up to 100 times more potent, making the risk for overdose much greater. Last year, fentanyl was present in 84 percent of drug-overdose deaths in Philadelphia and in 65 percent of overdose deaths across Pennsylvania.

Nearly all fentanyl in Philadelphia is produced in China, according to the Drug Enforcement Agency. The majority of it is secreted across the border, while some is sent through the mail.

The Trump administration has been pushing Chinese authorities to clamp down on fentanyl production since it drove a spike in overdose deaths several years ago.

Effective May 1, the Chinese government will schedule fentanyl and all its related substances as a class of controlled drugs. The regulation is designed as a disincentive to produce the drug there, and to make it easier for Chinese law enforcement to crack down on fentanyl manufacturers. But experts and public officials wonder if the announcement is simply lip service to the U.S. government’s request.

“If there were less fentanyl on the street, we would expect to have fewer people die of drug overdose,” said Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley. “What I don’t know is whether the actions in China will actually reduce the amount of fentanyl sold on the street. Now that people understand how to synthesize this chemical, there may very well be other sources that fill that gap.”

Because it is completely manufactured in a lab, fentanyl’s chemical makeup can be slightly altered without substantially changing its effect, making it very difficult to regulate, according to Patrick Trainor, supervisory special agent with the DEA in Philadelphia.

“In the past, when we would schedule fentanyl, a lot of the manufacturers overseas would modify the chemical composition, which would then, in effect, change the drug, thereby making it essentially legal,” Trainor said.

By scheduling all fentanyl’s analogues and precursor substances, China hopes to safeguard against this loophole.

But whether Chinese officials actually will do what it takes to enforce the regulations remains unclear. Historically, the Chinese government hasn’t given much indication that it wants to or can regulate the fentanyl market, according to Roger Bate, health economist with the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute.

“In China for the best part of the decade, if you’ve been producing chemicals for pharmaceutical production, you’re supposed to be regulated carefully by the equivalent of the China FDA,” said Bate, who focuses on counterfeit drugs and substandard medicine. “But in reality, the Chinese authorities haven’t enforced that rule at all until a few years ago, and weakly since.”

Bate said the move to close the loophole and schedule fentanyl and all its analogues as a class does represent what he called a sea change, at least rhetorically. But whether the policy translates to a slower flow of drugs to the United States depends on a combination of political will and real enforcement capacity.

“China is the largest producer of precursor chemicals in the world,” said Bate. “It’s a major part of the Chinese communist mantra that they will find employment for nearly everybody. So anything that reduces employment by several million is going to be frowned on and likely not enforced.”

Bate added that even if the Chinese government wanted to enforce the new regulations, doing so would be difficult based solely on the large number of pharmaceutical manufacturers throughout the country. There are also fentanyl production industries in other countries, including India that could fill the gap of U.S. supply if the flow was stemmed from China.

In a press conference in April, Liu Yuejin, head of China’s National Narcotics Control Commission denied that it is the main source of fentanyl flowing into the United States, and blamed the problem on addiction here.

Despite that, Bate said negotiating a trade deal with the United States may provide some incentive for Chinese officials to take the new regulation seriously.

“Fentanyl and its analogues make China tens, maybe hundreds of millions of dollars a year, they don’t make it tens of billions,” he said. “I think the other areas of the free trade deal are much larger. For self-interested economic reasons, the Chinese should clamp down on fentanyl production, and that I think is our greatest hope.”

Disclosure: The American Enterprise Institute’s Roger Bate is the husband of WHYY reporter Dana Bate.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.