Cellular powerhouses explain why alcoholics have weaker muscles

Photo via ShutterStock) " title="ssmitochondriax1200" width="1" height="1"/>

Photo via ShutterStock) " title="ssmitochondriax1200" width="1" height="1"/>

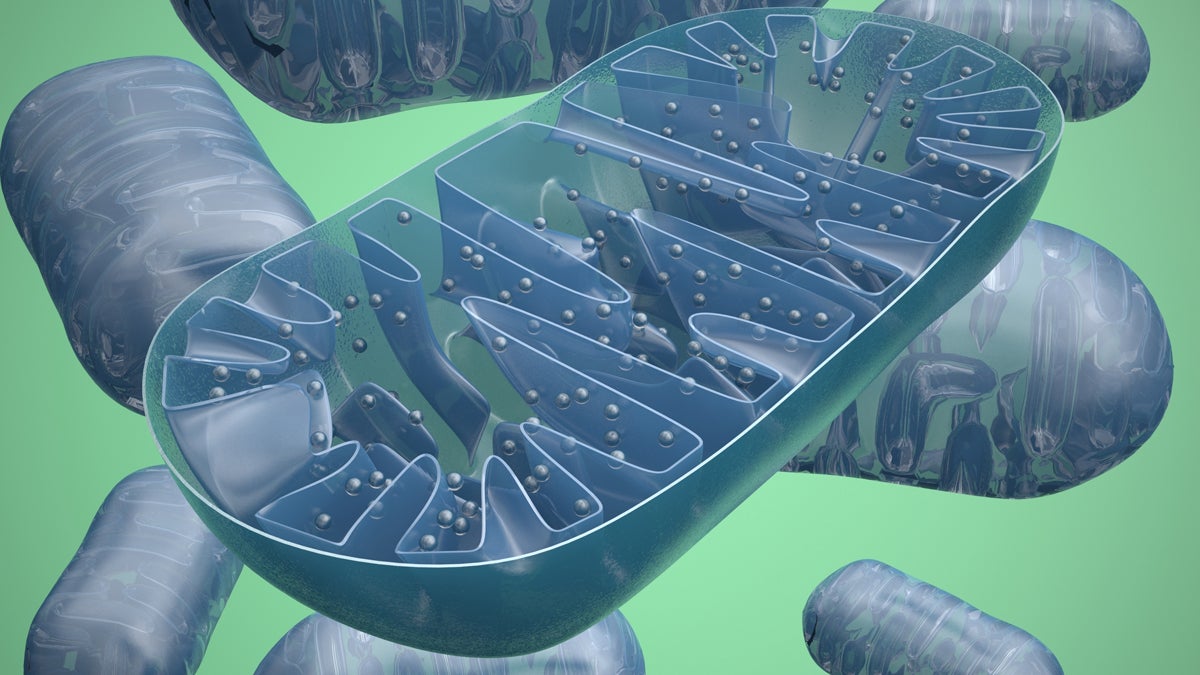

Mitochondria are membrane-bound cell organelles (mitochondrion, singular) that generate most of the chemical energy needed to power the cell's biochemical reactions. (Photo via ShutterStock)

Doctors know long-term alcohol abuse makes muscles weaker, but scientists haven’t had a good explanation for why that is — until now.

New research from Thomas Jefferson University suggests staying strong has a lot to do with keeping our mitochondria healthy.

Mitochondria are less than a micron in size, but they’re our cellular powerhouses. Gyorgy Hajnoczky, a Jefferson professor of cell biology and senior author of the latest study, said as mitochondria pump out energy to fuel our cells, toxic by-products of that process damage the mitochondria.

“Recycling of the whole [damaged] mitochondria is difficult and energy-expensive,” he said. “Replacing components by fusion seems to be a very practical way to keep them in shape.”

This type of fusion was known to occur in cell cultures, but Hajnoczky said it wasn’t at all clear if it happened in skeletal muscle, where the mitochondria are packed in so tightly that it was thought to be hard for them to move.

To find out, researchers in his lab used fluorescent proteins to label different mitochondria in rats — and saw lots of yellow spots where the mitochondria had successfully fused.

But when researchers fed the rats a steady diet of alcohol, they saw far less yellow. The mitochondria weren’t fusing together to swap parts and stay healthy.

“I think it gives a simple explanation that with the damaged powerhouses the muscles don’t have enough fuel to pump powerfully,” said Hajnoczky. “So it gives a new mechanistic explanation for the muscle weakness experienced by these patients.”

The team was able to tie the reduced fusion in the alcoholic rats to lower levels of a particular protein. It’s not yet clear if the same is true in humans. But Hajnoczky said, if so, it will open the door to new drug treatments.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.