‘Artificial womb’ invented at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Listen

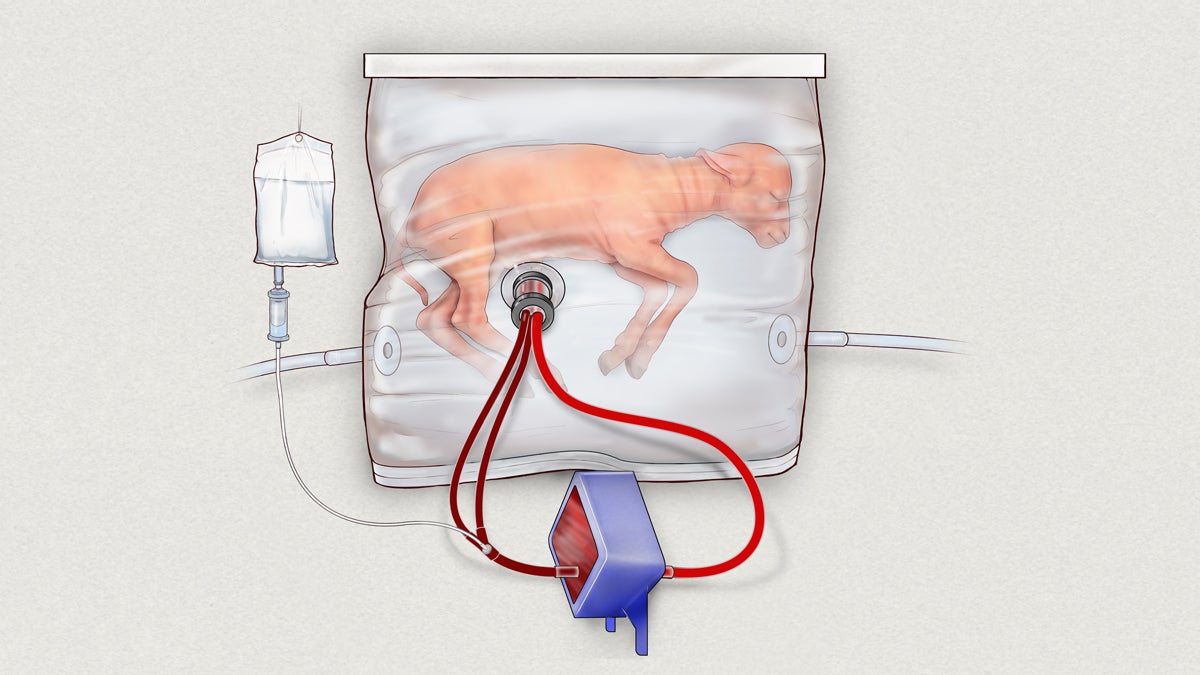

Biobag system consisting of a pumpless, low-resistance oxygenator circuit, a closed fluid environment with continuous fluid exchange and an umbilical vascular interface. (CHOP)

Researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia have created a device that could revolutionize care for babies born extremely premature.

The invention mimics the mother’s womb, and could allow these vulnerable infants to continue to develop as if they were still in utero.

Advances in technology have allowed many babies delivered after only 22 to 23 weeks to survive. But most of these extreme premies suffer permanent disabilities such as cerebral palsy and lung disease.

“Currently, there’s no way to support these infants without those associated problems,” said Alan Flake, a fetal surgeon at CHOP and co-inventor of the device.

That’s where the “artificial womb” device comes in. In the system, which has only been tested in animals so far, the premature infant is placed in a plastic bag filled with a substitute for amniotic fluid. The baby breathes in the fluid, allowing for continued lung development, while the heart pumps blood through a circuit of tubes connected to the umbilical cord. As it circulates outside of the plastic womb, the blood is infused with oxygen and nutrients before returning to the neonate.

“We’ve actually been able to replicate the normal physiology of the fetus,” said Flake.

The CHOP researchers tested the device in premature lambs, and published the results of their research today in the journal Nature Communications. The eight lambs in their study showed normal development in the artificial womb for up to four weeks. In human terms, that amount of time would allow some of the most premature babies to continue to develop as if they were still in the womb for long enough to escape the high-risk period for the worst complications.

The invention is not intended, however, to support babies born even earlier than current technologies allow. Nor could it replace the biological womb altogether. The idea that an embryo could develop into a fetus outside of a real, biological mother is pure science fiction, said Flake.

“The most important period for developmental events is still entirely dependent on mother nature,” Flake said. “There is no technology that can fill that gap.”

The researchers are now working with the FDA on preliminary studies to clear the way for the first clinical trial of the device in human babies. They hope to be ready to run such a trial at CHOP in three to five years.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.