Exclusive: Finding Reverend Gloucester

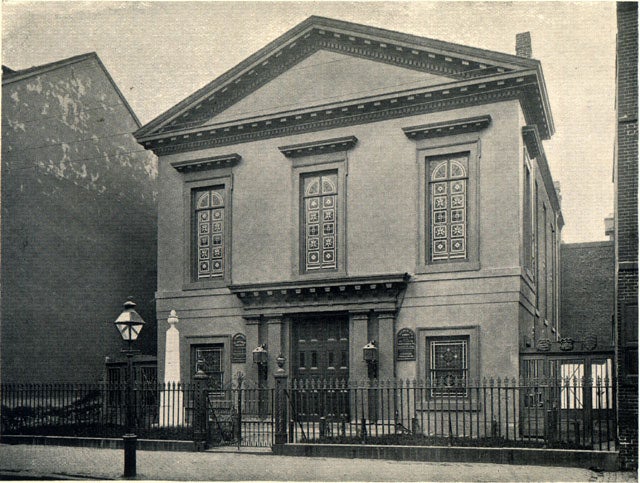

The church with Rev. Gloucester’s burial marker. No one knows what has become of that.

Nov. 22

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

Born a slave in Tennessee, Stephen H. Gloucester spent his adult life in Philadelphia, fighting for the freedom, education and civil rights of African Americans in 19th Century America.

He ran a school for black children, assisted the Underground Railroad, founded at least two anti-slavery societies, and was one of the publishers of the Colored American, described by The Black Abolitionist Papers as perhaps the most important African American publication of its time.

Reverend Gloucester was already nationally known in 1844, when he founded Lombard Street Central Presbyterian Church. But nearly 160 years after his death, Gloucester’s grave lay unmarked and unknown to most in modern Philadelphia.

That is about to change.

This is the story of the husband-and-wife team of developers, two archaeologists and an anthropologist who found Gloucester’s remains in front of the white, Greek Revival church he founded, and the efforts they and a group of church leaders are taking to honor his memory and resurrect his legacy.

Rev. Gloucester

The Gloucester History

Stephen Gloucester was born in 1802, one of the four sons of John Gloucester, who was the first African American to become an ordained Presbyterian minister in the United States.

According to a brief biography posted on the website of the John Gloucester House – an outreach center operated by the Philadelphia Presbytery in Point Breeze – the elder Gloucester was purchased by a white Presbyterian minister named Gideon Blackburn, who saw in him potential for the ministry. He was ordained in Tennessee, but came to Philadelphia in 1807 at the request of Archibald Alexander, a Presbyterian minister and chairman of the Evangelical Society of Philadelphia.

John Gloucester founded The First African Presbyterian Church at Girard Avenue and 42nd Street, which had 123 members by 1811. He traveled as far as England to borrow money from friends – including Benjamin Rush – in hopes of buying his family’s freedom. When Stephen Gloucester was 12, his father purchased his freedom for $400, and he joined him in Philadelphia. (John Gloucester was also able to purchase the freedom of his wife and his other three sons, who also became ministers.)

In adulthood, Stephen Gloucester became an activist.

Between 1820 and 1840, Reverend Gloucester ran a school for black children and established a reading room for black adults. He was among the group of people primarily responsible for Underground Railroad activities in this city. He organized the Leavitt Anti-Slavery Society and encouraged black churches to start similar groups, and was one of eight black pastors who founded the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1938, he became a publisher and proprietor of the Colored American. The publication advocated for abolition, educational improvements, and civil rights while rallying against prejudice and oppression.

In 1831, Gloucester married Anne Crusoe of Washington, D.C. and raised a family with her. Gloucester was a talented fundraiser who held fairs in Philadelphia and New York to raise money to pay off the Second African Presbyterian Church’s debts. The Gloucesters did not themselves become wealthy, however. Anne took in washing and Stephen sold used clothes to supplement their income.

When the pastor of Second African Presbyterian died, the congregation appointed Gloucester to take over. But the church became a victim of the prejudice and oppression that Gloucester fought.

A mob destroyed Second African Presbyterian in the 1842 race riots. The event profoundly changed Gloucester’s personality and activism in ways that led some abolitionists to condemn him.

After the church was destroyed, he feared for the safety of his family and other black people as a direct result of abolitionist activities.

According to the Black Abolitionist Papers, “he became cautious, defensive and accommodating. In soliciting funds to build a new church, he publicly disavowed his church’s involvement with abolitionism.” Gloucester did not change his anti-slavery stance, nor did he cease his work to help the black community. But he distanced himself from the abolitionist movement, and took on a less aggressive demeanor.

In 1844, Gloucester became the founding pastor at Lombard Street Central Presbyterian Church – a church that was formed after the congregation of Second Presbyterian split into two factions.

While in Britain in 1847, Gloucester spoke both to the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and the Free Church of Scotland, which, according to the Abolitionist Papers, was known to associate with slaveholders. He criticized the abolitionist movement as “violent, impolitic and detrimental to the anti-slavery cause,” thus enraging abolitionists at home and abroad.

Frederick Douglass is said to have called Gloucester “one of the vilest traitors to his race that ever lived.”

This schism with other activists led Gloucester to concentrate on his church, which moved into the white, Greek Revival-style building on the 800 block of Lombard upon its completion in 1848. The church eventually dropped the “street” in its name and became known as Lombard Central Presbyterian. In 1850 while on a church-related trip to Reading, Gloucester died of pneumonia. President Abraham Lincoln would not sign the Emancipation Proclamation for another 13 years.

Gloucester’s congregation buried him in a brick vault in the front of the building he had raised money to construct. There they placed a marble obelisk, inscribed:

Rev. Stephen Henry Gloucester

First Pastor of the

Lombard St. Central Presbyterian Church

Died May 21st, 1850

Aged 48

Erected by the Congregation and Citizens among whom he labored, as an expression of esteem and affection for him – a devoted and successful minister of Jesus Christ.

In 1880, Ann Gloucester died, and her remains were placed with her husband in the brick vault.

At some point since an 1895 photograph was taken, the large obelisk that marked the Gloucesters’ grave went missing.

In 1939, the congregation outgrew their original church, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, and moved to a historic former Quaker meeting house on Powelton Avenue in West Philadelphia.

Lombard Church Elder Jerry Cousins, 82, said he was not a member back then, but his late wife was. Cousins, who joined the church 10 years later, said the congregants knew their founding pastor was there. “They didn’t have a burial spot, so they just left the remains where they were,” he said.

For a time after the Lombard Church left, another church held services there. But developers Naomi Alter-Ohayon and Isaac Ohayon say the building had been vacant for at least 50 years when they bought it about four years ago.

The Developers

The Ohayons had considered buying the former church more than a decade earlier, when it was up for auction. “I’ve always loved it since the first time I saw it,” Isaac Ohayon said. They offered $35,000. The couple was just starting their rehab and development business, Masada Custom Builders, and Naomi Ohayon said she was intimidated by the building. When someone else bid $45,000, they let it go.

But while the couple was gaining experience – including the renovation of their own home, which they had planned to sell but couldn’t part with – nothing ever happened with the building they were so drawn to. So four years ago, they bought it for $500,000 – a price which included rotting wood, a small flock of pigeons, and a tiny kitten who is now the Ohayon’s fat cat, Whiskers.

The couple is now in the process of converting the worn-out structure into a 10,000 square foot luxury home they hope to sell for $4.95 million. This past summer, while beginning the landscaping for the front yard, workers hit a piece of slate.

“We removed the slate, and we found a hole,” Isaac said. They also saw the domed brick vault. They called the Historical Commission, a group they were already working with to get assistance in accurately restoring the church’s façade, and learned that the Gloucesters had been buried there.

There is no law requiring the developers to move the remains. But the Ohayons said they did not feel right leaving anyone buried and forgotten beneath a front lawn. And the more they found out about Stephen Gloucester, the more intrigued they became.

At the Historical Commission’s suggestion, the Ohayons called The Philadelphia Presbytery and an archaeologist.

The Archaeology Team

Senior Archaeologist Douglas Mooney, Project Archaeologist, Kim Morrell and Forensic Anthropologist Thomas Crist, all with URS Corporation, Inc. of Fort Washington, spent the past week at and in the Gloucester’s vault.

Mooney did not at first expect to find the Gloucester’s remains in the vault. He knew Lombard Central had moved, and he thought there was a strong possibility that they had taken their pastor and his wife with them.

Mooney had heard second-hand that someone had broken into the grave in the past. When he began working at the site, he saw a jagged hole cut into the vault. “Someone had been in the vault before,” he said.

But everyone wanted to be certain, so they began removing the six feet of soil the vault contained.

Not only were human remains found, but there are three sets. The third is thought to be those of John Winrow, a member of the congregation who died in 1853 and requested to be interred in the vault, Mooney said.

On Friday, the archaeology team removed the remains from the vault as snow steadily fell.

“Snow is better than rain,” Crist said. “Rain is the enemy of archaeology, because all the dirt turns to mud, and nothing will go through the screen.”

Morrell – who has been involved with the re-interment of several thousand sets of remains – gingerly brushed away the last layers of dirt.

No caskets remained in the vault, she said. There were some small wooden fragments, but the rest of the wood had dissolved into “just something like a clay-like smear,” she said.

She handed Mooney some remnants that did survive: A handle, thought to be brass, and some ornamental elements made from a lead alloy. A few minutes later, her brushing revealed several white buttons.

“These would have been at the elbow,” she said.

Mooney said in an email Saturday morning that all evidence at the site backs up the documentary evidence that the vault contained the remains of the Gloucesters and Winrow. Now Crist, who works for URS on an as-needed basis but spends much of his time teaching at Utica College, will use forensics for the final confirmation.

Each set of remains will be identified. The bones reveal ethnicity, gender and age. The team already knows that Rev. Gloucester was 48 when he died, and, assuming Ann Gloucester was roughly her husband’s age, she would have been in her 70s when she died. Two sets of remains were found on the bottom of the vault, Mooney said, and they would be the two people who died first – Rev. Gloucester and Winrow. If Winrow and the pastor were the same age, the placement of Ann Gloucester would identify her husband – her casket would have been placed on top of his.

The Ohayons estimate that the work of finding, recovering and reburying the remains has added about five months and $15,000 to their project, but they have no regrets.

“We didn’t feel like it was right to just cover it up and move on,” Naomi Ohayon said. “We wanted to do something respectful.

Mooney praised the couple for their decision. “This is someone who deserves a place where people could go to his grave site.”

Two Churches, the Past and the Present

Reverend and Mrs. Gloucester – and almost certainly Mr. Winrow – will have a public, marked resting place.

Soon after he realized who was buried in front of the property, Isaac Ohayon visited the new Lombard Central Church in West Philadelphia.

He went early, hoping to talk to someone before services began, but things had already gotten started when he arrived. “The service was amazing, full of soul and music,” he said. The woman leading the service, Anna Grant, asked visitors to identify themselves, and Ohayon was welcomed.

During the service, Grant said, “I feel something happening, there is something that I feel right now.” Considering his mission was to tell church members that the remains of their founding pastor had been found, Ohayon was profoundly struck by Grant’s words.

Afterward, he approached Grant to tell her the news about Rev. Gloucester, and she called over Elder Cousins.

Cousins said that old Lombard Central still had no place to bury their first pastor. The Presbytery set out to find a proper burial site. After discussions with the present-day leadership of Lombard Central, the Black Caucus of the Presbytery of Philadelphia, and the National Black Caucus of the Presbyterian Church, the Presbytery contacted Third, Scots and Mariners Presbyterian Church, more commonly known as Old Pine Church.

Donna Irvin, an elder at Old Pine, said accepting the remains was an easy decision. The church has in the past accepted remains in need of a final resting place into their historic graveyard, she said, but this case goes beyond even that: The Gloucesters are part of Old Pine’s family.

The Presbyterian minister who brought Stephen’s father, John Gloucester, to Philadelphia, was pastor of Old Pine. “Archibald Alexander was the mentor of John Gloucester,” Irvin said. “Old Pine and First African Presbyterian Church have through the years celebrated their history together.”

Old Pine is also in the same neighborhood as the Lombard Street church. “We felt we could make them at home in our yard,” Irvin said. “This is where he should be.” Irvin had not heard about the discovery of a third set of remains, but said she could not imagine that John Winrow would be turned away from Old Pine.

The Gloucesters’ grave will be marked with a plaque commemorating Rev. Gloucester’s life. In coming weeks, they will be reburied with a full Christian service attended by members of both Lombard Central and Old Pine. That service will be private, but a public ceremony and commemoration of the Gloucesters will be held later this winter, Irvin said.

Old Pine’s churchyard is open daily until sundown. Congregant Ronn Shaffer has spent a lot of time documenting the lives of the people buried their, Irvin said, and he frequently takes visitors on tour. Soon, Stephen Gloucester will be part of that tour, Irvin said. “This is a chance to reclaim his story, as Old Pine has tried to do with many other people whose stories would have been lost,” she said.

“It means a lot,” said Lombard Central Presbyterian Elder Cousins, who plans to attend the service. “I knew that they were planted there at 9th and Lombard, and I never thought anything like this would come about.”

Cousins said it was very important to honor Stephen Gloucester. “That church was founded in 1844, and there was a lot going on back then,” he said.

“Gloucester was a great man – not just in being a pastor, but in other ways as well,” Cousins said. “All these many years have gone by, and a lot of people, even in the Presbyterian Church, even a lot of African Americans, don’t know too much about him. To have his remains found and replaced again, I think it’s a great thing.”

Gloucester’s Church Today

Lombard Central Presbyterian, the church that left its original home because it outgrew it, now has about 40 members, Cousins said.

It remains a vibrant place of worship today, but it has not always been easy. The church has not had a pastor of its own since 1995. “We’ve struggled ourselves to keep the church going,” Cousins said of the elders and members. Some of the elders became ordained to give sermons, he said. And the church has arrainged for a long stream of guest pastors.

“Thank God, in the last 12 years or so, the pulpit has never been vacant,” Cousins said.

But as the remains of Stephen Gloucester are prepared for burial in a place of honor, the congregation at the church he founded is focused on both the past and the future.

Anna Grant – the woman leading the service when Isaac Ohayon visited – has done most of the preaching at Lombard Central for four years, and all of it since September.

She grew up in Gloucester’s father’s church, First African Presbyterian, and is an ordained Baptist minister. But Rev. Grant is poised to become Lombard Central’s first pastor in more than a decade. The Philadelphia Presbytery is in the process of determining whether to accept her credentials or require her to take the Presbyterian ordination exam, she said.

Grant said while her church would have loved having their founder’s grave on site, Old Pine is really a better place. He will be among prominent Philadelphians – including William Hurry, who rang the Liberty Bell when the Declaration of Independence was signed, and Jarred Ingersoll, who signed the Constitution. At Old Pine, more people will get to learn who Gloucester was, she said.

Grant said she is filled with awe thinking about leading the church founded by a man like Gloucester – and she gets the chills when talking about his focus on education. “Just listening to his accomplishments really encourages me,” said the woman who taught English and reading for 36 years in Philadelphia’s public schools. “We’re going to start an after school program, and maybe even a school.”

Grant has been compiling a history of Lombard Central, and she hopes to create an exhibit. Harriet Tubman spoke at the Lombard Street location, she said, as did William Stills, considered by many to be the father of the Underground Railroad.

The reported rift that occurred between Gloucester and other anti-slavery activists does not trouble Grant, who includes Frederick Douglass among her heroes.

“He stood up for what he believed,” she said of Gloucester. “I admire him for being able to stand up and say that he could see these things becoming too political, too violent,” he said. “What it says to me is that he was not at all concerned about what people thought, but about what he thought was right. I think it took a lot of guts.”

Note: The biographical facts of Gloucester’s life were taken from The Black Abolitionist Papers, Vol. 3, The United States, 1830-1846. C. Peter Ripley, ed., pp. 198-200 and/or provided by archeologist Douglas Mooney, unless otherwise stated.

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.