In restored surroundings, Rodin sculptures again have room to breathe

After four years of renovation, and more than a year of being shuttered, the Rodin Museum now has that new-museum smell.

The olfactory cocktail of cleaning solution and polyurethane means the tiny Beaux Arts jewel box on the Parkway has been scrubbed and primped, top to bottom.

Nestled in a fountained garden, the Paul Cret-designed building displays the second-largest collection of sculptures by French artist Auguste Rodin. The Rodin fills an essential gap in what is being called Philadelphia Museum Mile, positioned next to the Barnes Foundation and across the street from the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“The Rodin, as you drive up and down the Parkway, is much more visible than it used to be,” said art museum director Timothy Rub, standing in the pruned and bloomed garden. “There’s a much better relationship between setting and building.”

The museum opened in 1929 by the posthumous ambition of Jules Mastbaum, a early admirer of Rodin’s work. It is now operated by the art museum, which has invested millions into restoring the sculptures, the galleries, and the grounds to their original design.

The walls are now covered in linen, as per Cret’s plans, and new terrazzo podiums were recreated from the original specs. A Pompeii-red color scheme has returned to the small side galleries.

Imposing sculptures regain outdoor space

Most dramatically, the large outdoor sculptures have been put back outside.

The main gallery had been dominated by “The Burghers of Calais,” a grim piece of six life-size men with nooses around their necks, sacrificing themselves to King Edward III. Acid rain had burned the green patina of the sculpture with gray streaks.

The gallery was also stuffed with other life-size figures such as “Eve” and “The Age of Bronze.” They have been restored put on pedestals and wall niches in the garden. Perhaps fittingly, the moody “Burghers” have kept their distressed patina.

“These sculptures for the last 45 years had been in the main gallery of the building, where they looked very nice but they were crowded,” said associate curator Jennifer Thompson. “They elbowed each other, and the scale of the architecture wasn’t designed to house these large pieces.”

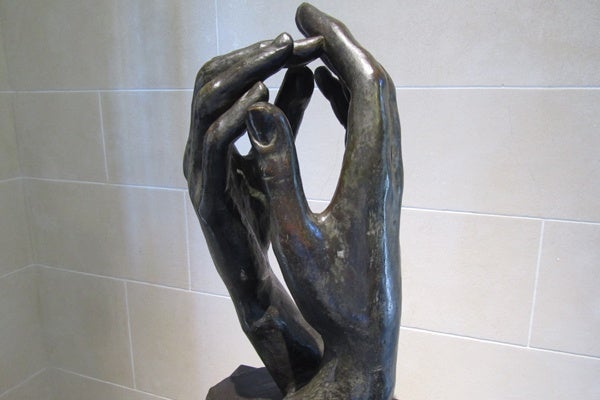

The gallery now houses many smaller pieces, including enlarged body fragments (the folded hands of “The Cathedral”) and small mythical creatures (the sensual and slightly bestial “Kneeling Fauness”) that have more space to breath.

‘Gates of Hell’ and its reiterations

Twenty of the small sculptures are figures that appear in Rodin’s monumental masterwork “The Gates of Hell,” one of only seven extant confronting visitors as they approach the building. The 20-foot bronze doors are bursting with more than 200 figures articulating different means of human suffering, based on Dante’s “Divine Comedy.”

Rodin spent 37 years making that work. He sometimes gave the suffering figures a life apart from the gate.

“Rodin found ‘The Gates of Hell’ an extraordinary source of inspiration,” said Thompson. “He would pull individual figure groups off the gates throughout his career, enlarge them, make subtle changes, and then exhibit them as independent works of art.”

The smaller works take new meanings when divorced from ‘Hell.’ Lovers embracing, for example, represent a deadly sin when surrounded by demons, but on their own they are passionate and sensual.

“Every time you shuffle the deck and deal it again, new and interesting things happen,” said Rub. The art museum has about 150 pieces by Rodin in its collection, 90 of which are on display. The museum intends to rotate and reinterpret the collection every few years.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.