Young man and the sea: Hemingway’s Philly connection

Listen-

Christina Love

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

To mark the anniversary of Hemingway’s 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature, an Academy of Natural Sciences fellow is among 14 Americans traveling to Cuba to protect the fish that were so important to the author’s life and work.

Ernest Hemingway is best known for his iconic novels at the core of the English cannon, but significantly less well-known for his contribution to marine science: An avid sport fisherman, Hemingway hosted two Philadelphians on a research expedition off of Cuba for six weeks in 1934.

This week, to mark the anniversary of Hemingway’s 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature, an Academy of Natural Sciences fellow is among 14 Americans traveling to Cuba in an effort to protect the big game fish that were so important to the author’s life and work.

Hemingway’s historical ties to Philly

In 1934, the Academy’s fish expert Henry Fowler was researching a book on big game fish of the Atlantic. Hemingway invited Fowler and the Academy’s director Charles Cadwalader to join him on his beloved fishing boat, the Pilar, for six weeks of fishing in the Florida Straits.

“Every day, the three of them went out on the boat, looking at fish, talking about fish and trying to catch fish,” said Academy Senior Fellow Bob Peck.

Fowler and Cadwalader balanced out the famously hard-drinking Hemingway, who took his contribution to science seriously on the trip.

“Hemingway, it turns out, had a great deal of knowledge in this subject, he was a sports fisherman, yes, but he was also a very keen observer,” Peck said.

“Hemingway realized that in order to get the correct identification of the fish and to understand what they looked like in the wild, Fowler and Cadwalader would need to see them coming out of the water and onto the deck, so their colors hadn’t changed yet.”

For years after the expedition, Hemingway maintained a correspondence with Academy scientists, sending specimens he caught and accounts of his fishing trips back to Philadelphia.

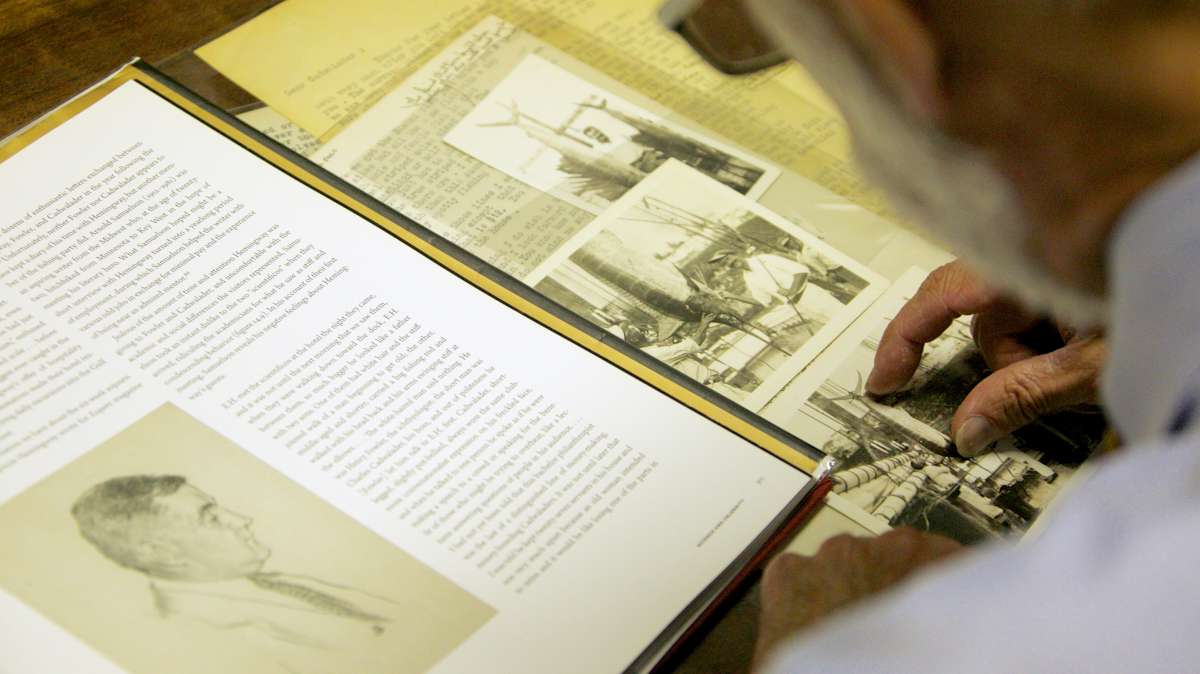

The Academy now has in its collections a few dozen black-and-white photos and yellowing letters, some hand-written and signed, from the author. An early letter, written during an Atlantic crossing, has a downward slanting script that betrays the motion of the seas on board.

Another 1934 letter to Fowler describes a tuna Hemingway shipped by ferry to be re-packed in ice in Key West and shipped on to Philadelphia.

“This fish in life was a dark purple on the back, opalescent on the flanks and belly, with a gold rather than silver shine.” Hemingway wrote. “The fins were purple, blue on top, and silver on the bottom.”

“You can see how specific these descriptions are, he’s very precise in how he’s describing this,” Peck said.

The author had a sense of humor when writing Fowler, calling himself a “lousy, ignorant fisherman” who did not want to “poke my large, inflamed nose into scientific matters,” and suggesting that Fowler eat the tuna if it wasn’t worth saving.

“If you don’t want him as a specimen and he gets there in good shape, wash the salt out, cut the meat off both sides of the backbone and broil it,” Hemingway wrote.

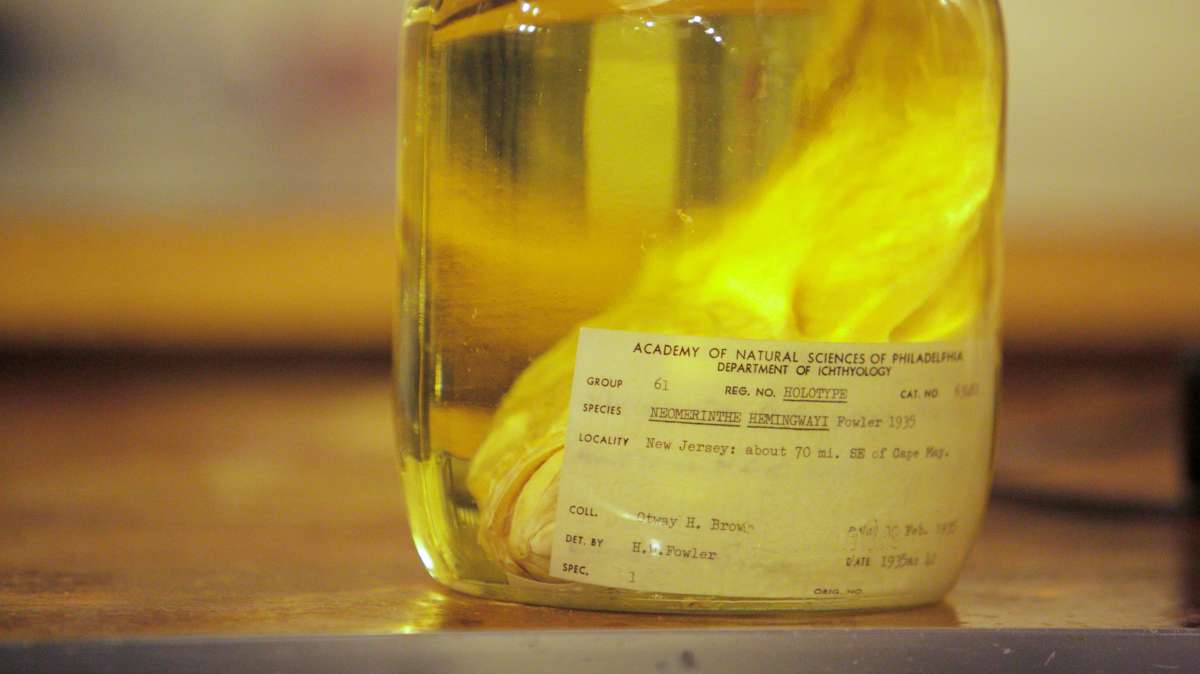

The Academy did not, in fact, broil the tuna. It is still in their collections, leeched of the purple and gold pigments Hemingway so elegantly described but otherwise well-preserved in a glass jar of ethanol.

A black-and-white photo in the collection shows Hemingway on a boat deck with two Atlantic sailfish hanging on either side of him. He is tanned and youthful, with thick brown hair, a moustache and a self-satisfied grin.

“We think of him of course as the great bearded, iconic figure,” Peck said, “but here he is a much younger man, clearly in the prime of life. He’s really just like a boy who’s so excited about catching these fish.”

According to Peck, during the trip, Hemingway gathered details about weather and the Gulf Stream from Fowler and Cadwalader that he would later use in his book “The Old Man and the Sea.”

The classic story is about an epic struggle between Santiago, an old fisherman on a streak of bad luck, and a massive blue marlin he labors for days to reel in.

‘Science knows no boundaries’

On Monday, Peck sailed with Hemingway’s grandsons from Havana to Cojimar, the fishing village that inspired “The Old Man and the Sea. ” The group also met with Cuban marine scientists to discuss creating a joint US-Cuba fish-monitoring program.

With the onset of industrialized fisheries, large fish populations around the world plummeted by more than 90 percent in the second half of the twentieth century.

Marlin, sailfish and tuna travel extensively between Florida and Cuba, but Peck said because of the embargo there is little communication between scientists on either side of the Florida Straits.

“As Hemingway would have been the first to argue, science really knows no boundaries,” Peck said. “As these fish become more and more endangered by overfishing and environmental concerns, this is a time for our countries to reach out and to work cooperatively to try to protect the fish.”

Hemingway and the Academy scientists never returned to the sea together after the 1934 expedition.

Fish expert Fowler, however, was so grateful for his time on the Pilar, that in 1935, when he discovered a fish off the coast of Cape May, he named it after the author: the Neomerinthe Hemingwayi, more commonly known as the Spinycheek Scorpionfish.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.