To lower suicide rates, connecting with men is key

Listen

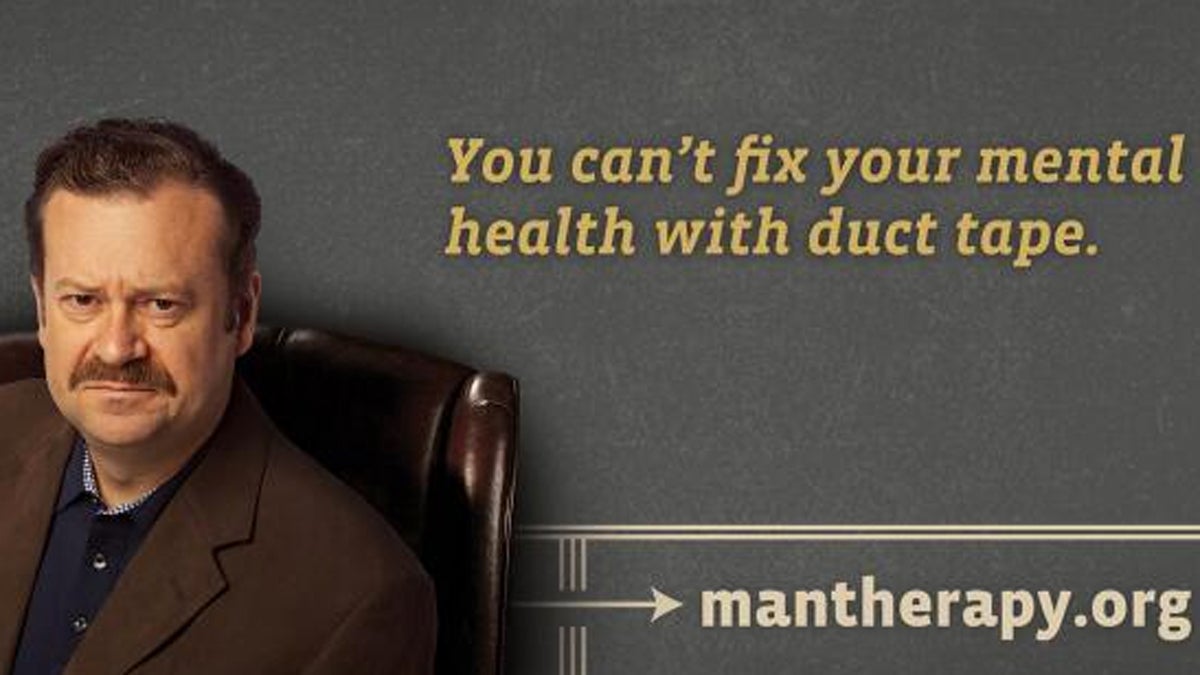

Hello, I'm Dr. Rich Mahogany, welcome to Man Therapy. (Courtesy of mantherapy.org)

Since 2005, the country’s suicide rate has been steadily rising, and if public health officials want to reverse that trend, they’re going to need to talk to men in a language they understand.

Dr. Rich Mahogany’s therapy office would fit well in a hunting lodge. Dark wood desk, dark-paneled walls with a moose head, a dartboard, old books, old lamps. He looks just like Ron Swanson on the TV series “Parks and Rec.”

“Did you know that men have feelings too?” he asks on his YouTube channel, “Not just the hippies, all of us. Hello, I’m Dr. Rich Mahogany, welcome to Man Therapy.”

He’s got a whole series of videos. How to practice deep breathing. How to relax by making a batch of “Guaco-Mahogany.” And practicing yoga, in gruesomely small shorts.

Mahogany is a fake doctor, played by an actor. But these videos aren’t just sketches. They’re part of a highly calculated campaign to reduce suicide in working-aged men, by using comedy as a way in to talking about mental health.

“The increase in the overall suicide rates,” says Center for Disease Control (CDC) epidemiologist Alex Crosby, “has been driven primarily by the increase among working age adults.”

When someone dies by suicide in the U.S., it gets noted on their death certificate. Suicides are coded as “X” and then a number, depending on the method. For example, if a rifle was used, it’s coded as “X73.” Those codes go to the CDC, where they compile all of the demographic data.

“One of the things about suicide rates and suicides in the United States,” says Crosby “is the majority occur among males, about 80 percent.”

So if you want to be purely rational about it, to have the most impact on the U.S. suicide rate, you target men aged 35-64. But so far, that hasn’t really happened.

“Most of the money in suicide prevention has gone to youth suicide prevention, and so we’re glad to see that that’s paying off,” says Sally Spencer-Thomas of the Carson J. Spencer Foundation. “But men in the middle years are not considered often a category that is needing extra resources. It’s just been a population that hasn’t been addressed, in terms of their own mental health needs and their own mental health crises.”

Her foundation tries to fill that gap with the “Man Therapy” campaign. It’s based out of Colorado, but other states have co-opted it.

There are Dr. Mahogany billboards, drink coasters at bars, signs above urinals. All kind of winking at stereotypes about masculinity, and feelings. The Man Therapy website has a five-minute quiz to assess your mental health and it shares resources to help men help themselves. The foundation created Dr. Mahogany with the help of an ad agency, and focus groups full of working age men.

“It’s this subtle ah-ha moment for men,” Spencer-Thomas says, “‘Of course I have feelings. Why am I trying to deny that I having feelings?’ And he walks men through this process of acknowledging that the stereotypes are actually getting in their way.”

She says using comedy in the context of mental health can feel risky, but it’s what her focus groups said they needed.

Spencer-Thomas also heads the workplace task force at the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. They’re trying to also reach men by encouraging conversations around mental health at work. Companies with lots of male employees, like Union Pacific Railroad, the NFL, Facebook, are all on board too.

“I really think if my brother had other peer men who said, ‘Of course, I’ve had similar struggles. Let me hear your struggles, I’m here for you,’ it would have made a huge difference,” she says.

Spencer-Thomas’s brother Carson died by suicide in 2004. He’d been a successful businessman, and had felt really ashamed about having a mental illness. She says she’s seen in her work that men dealing with emotional issues can really benefit from seeing other men deal with tough stuff, and make it through.

Jane Pearson heads the suicide research group at the National Institute of Mental Health.

“We thought just treating mental disorders would, you know, take care of suicide, but it hasn’t.” She says.

Suicide rates right now are so high, higher than the rate for breast cancer. And it’s tempting to ask, what gives?

“Right,” she says. “And I think that for a lot of cancers, there [are] registries set up. There’s larger systems that will be systematic in testing different treatment approaches. We are just beginning to look at those different types of interventions within suicide.”

Pearson says it’s only been within the past about 10 years that researchers have really studied suicide as a thing in its own right, not just as an outcome of mental illness. And if there’s one thing that data shows us, it’s that suicide can be prevented. With therapy and outreach campaigns. But numbers also show that taking away popular means of suicide can prevent a lot of deaths. And when you’re talking about means of suicide and American men, you’re largely talking about guns. They’re the number one method.

“People often argue,” she says, “won’t someone just use a different method? But when people are suicidal, they have a particular plan that’s part of their constricted thinking of their one solution and if you can actually delay that, or distract them, the plan doesn’t go through. You have an opportunity to intervene.”

Researchers say this doesn’t have to be about getting rid of guns altogether. It could just be that when a gun owner is having a rough time, getting their friends or family to be aware of just how deadly that gun in their home could be.

Alex Crosby at the CDC says what we definitely need to fight suicide, is more data. They’re working right now on something called the National Violent Death Reporting Project. For suicides, it notes things like whether the person had attempted before, substance abuse history, whether they’d been getting treatment for mental illness. The hope is it will lead to better prevention efforts. The program is in 32 states so far, but they’re working to take it national.

The CDC is also funding a study to figure out just how well the Man Therapy program works. Results from that will be out in five years.

This is the second in Audrey Quinn’s three-part series on challenges facing the next director of the National Institute of Mental Health. You can listen to part one here.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.